In the Clifford sale, only one lot was bought in. In this sale, that number was fifteen out of the 146 offered. That number is somewhat deceiving, however, since only two of the truly important lots did not reach their minimums. Of the remaining unsold items, almost all were secondary works, such as later or scholarly editions, that were estimated at only a few hundred dollars for the most part. There were many such books in the sale, and they represented something of a democratic view in the auction room for this material. If a buyer could not afford to purchase an expensive first edition of an item, there was ample opportunity to purchase at least some copy of the text; in several instances, there were multiple opportunities to do so. Some of that material sold for prices rivaling or exceeding the first editions of lesser or more common titles. A couple of those books were, however, within the price range of even the most strapped graduate student. Both lots #37B, a modern English translation of Figueroa, and #66A, a second edition of Josiah Royce’s California, went for $23 each. Lot #68A, a modern scholarly edition of Shinn’s Mining Camps, went for $11.50 on an estimate of $10-20, thereby probably setting another Zamorano 80 auction record of sorts. In a Zamorano 80 sale, it is surprising to find such modest prices. In the Clifford sale, by contrast, the least expensive item at $34.50 was lot #26D, a scholarly edition of Dana’s novel accompanied by three more modern reprints. In its entirely, the Volkmann sale did very well, bringing just over $840,000 on low estimates of just over $609,000. By contrast, the Clifford sale brought about $269,600.

Estimating a sale such as The Zamorano 80 is certainly a challenge. Even without the potential complications caused by such things as the economy and the space shuttle disaster that occurred just before the sale, giving potential buyers realistic guidance about what they can expect to pay for such books in such a setting from such a collection is practically a unique exercise. There would be some guidance from previous sales for some of the material, but in the context of an entire Zamorano 80 collection, the bidding dynamics are probably a little tricky to predict.

For the Volkmann sale, Sloan altered her estimating technique. In the Clifford sale, she used traditional estimates that fell within fairly narrow bands (e.g., $300-450). For this sale, her estimates were almost always derived with an upper figure that was always twice the lower figure (e.g., $300-600). Taking the primary lots only, in the Clifford sale, 22 sold within their estimate range, 55 exceeded their high estimate, and only three (including the one bought in) went below their estimate. By contrast, in the Volkmann sale, 46 lots sold within their estimate range, only 29 exceeded their high estimate, and 5 (including the four bought in) went below their estimate. Of the fairly expensive lots in the Volkmann sale, nearly every one of them sold within the estimate range Sloan provided. Thus, over half the lots in this unique grouping of material sold for what Sloan predicted. The difficulty is ascertaining the low estimate, of course, and Sloan did a superb job of predicting that figure. Because such numbers probably depend on the dynamics of the bidders more than on traditional measures of value, nobody can predict such prices as Volkmann lot #17, the copy of Twain’s Jumping Frog that went for twice its already generous high estimate.

formerly the

Americana Exchange

Americana Exchange

US / Canada Toll Free

(877)-323-RARE [7273]

(877)-323-RARE [7273]

Rare Book Monthly

-

Sotheby's

Fine Books, Manuscripts & More

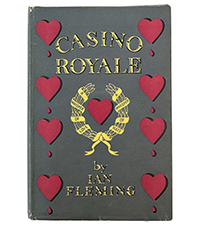

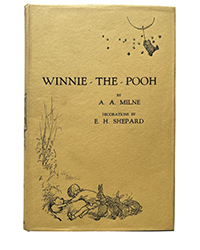

Available for Immediate PurchaseSotheby’s: Ian Fleming. Casino Royale, London, 1953. First edition, first printing. $58,610.Sotheby’s: A.A. Milne, Ernest Howard Shepard. Winnie The Pooh, United Kingdom, 1926. First UK edition. $17,580.Sotheby’s: Ernest Hemingway. Three Stories And Ten Poems, [Paris], (1923). First edition of Hemingway’s first published book. $75,000.Sotheby's

Fine Books, Manuscripts & More

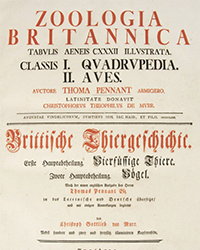

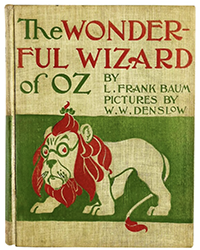

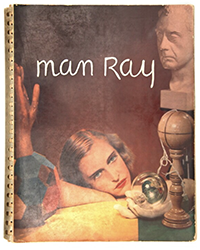

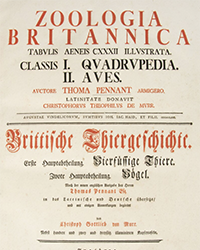

Available for Immediate PurchaseSotheby’s: L. Frank Baum. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, Chicago, 1900. First edition. $27,500.Sotheby’s: Man Ray. Photographs By Man Ray 1920 Paris 1934, Hartford, 1934. $7,860.Sotheby’s: Thomas Pennant. Zoologia Britannica, Augsburg, 1771. $49,125. -

Rare Book Hub is now mobile-friendly!

![<b>Sotheby’s:</b> Ernest Hemingway. <i>Three Stories And Ten Poems,</i> [Paris], (1923). First edition of Hemingway’s first published book. $75,000. Sotheby’s: Ernest Hemingway. Three Stories And Ten Poems, [Paris], (1923). First edition of Hemingway’s first published book. $75,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/acf970a0-a15d-4c79-aa24-5e8e414cb465.png)