WHH: I both add to it, and also I’ve been giving parts of it away. I’ve given parts to the Ars Medica or medical division of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. I’m also continually donating to the Library Company of Philadelphia as well. I give them mostly text, because the museum wants images, not text.

AT: You mentioned adding to your collection. Where do you acquire material?

WHH: From a variety of sources: I buy at auction, on Ebay, from dealers, at fairs. Just about anywhere.

AT: Is this the first time your collection has been exhibited?

WHH: Heavens no. I first exhibited parts of this collection in, it must have been 1964 or 1965. The collection had reached a critical mass at that point. I’ve done four shows at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

AT: Did you write all the caption labels in this exhibit yourself?

WHH: Yes, I did. Of course I had restrictions from the designers: I was restricted to 7 lines a label, tops. That’s why there’s more label text in the catalogue than in the show itself.

AT: Having curated an exhibit and written caption labels myself, I know that there’s always a subtle kind of tension between curators and designers.

WHH: Yes. What’s funny is that my daughter is also a designer. She just published a beautifully designed book about cardboard wheels called Inventing the Wheel. Her name is Jessica Helfand.

AT: Ok – a hated question, but one which I have to ask: which is your favorite piece in the show?

WHH: [skirting question] Well, to any collector, the last thing he got is the favorite. But you’ll find your own favorite.

AT: What do you hope visitors to this exhibit come away with?

WHH: I guess you could sum up the exhibit this way: when it comes to quacks, some of the cures were worse than the disease. Another focus of the exhibit is the itinerant nature of quacks, and the growth of medical advertising. Anybody could get into that business [the medical industry] with no license whatsoever. Until the 1840s only 4 US states had rules on who is qualified to practice medicine.

formerly the

Americana Exchange

Americana Exchange

US / Canada Toll Free

(877)-323-RARE [7273]

(877)-323-RARE [7273]

Rare Book Monthly

-

Sotheby's

Fine Books, Manuscripts & More

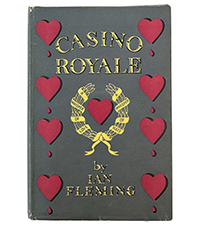

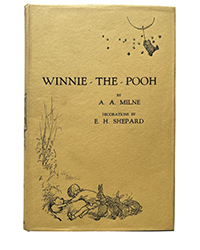

Available for Immediate PurchaseSotheby’s: Ian Fleming. Casino Royale, London, 1953. First edition, first printing. $58,610.Sotheby’s: A.A. Milne, Ernest Howard Shepard. Winnie The Pooh, United Kingdom, 1926. First UK edition. $17,580.Sotheby’s: Ernest Hemingway. Three Stories And Ten Poems, [Paris], (1923). First edition of Hemingway’s first published book. $75,000.Sotheby's

Fine Books, Manuscripts & More

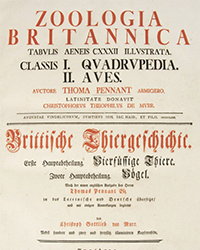

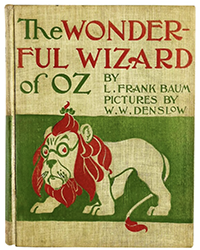

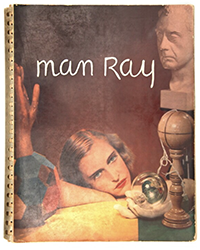

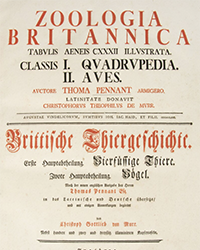

Available for Immediate PurchaseSotheby’s: L. Frank Baum. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, Chicago, 1900. First edition. $27,500.Sotheby’s: Man Ray. Photographs By Man Ray 1920 Paris 1934, Hartford, 1934. $7,860.Sotheby’s: Thomas Pennant. Zoologia Britannica, Augsburg, 1771. $49,125. -

Rare Book Hub is now mobile-friendly!

![<b>Sotheby’s:</b> Ernest Hemingway. <i>Three Stories And Ten Poems,</i> [Paris], (1923). First edition of Hemingway’s first published book. $75,000. Sotheby’s: Ernest Hemingway. Three Stories And Ten Poems, [Paris], (1923). First edition of Hemingway’s first published book. $75,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/acf970a0-a15d-4c79-aa24-5e8e414cb465.png)