The title of the latest catalogue from Jonathan A Hill Bookseller does not reveal much about its contents – Catalogue 233 Part I. We need to look inside to the two sections that are represented. There are five items of Early Printing in Japan 1297-1597 and 17 items of Movable Type Printing in Japan & Korea ca. 1596-1851. This is not a field with many followers in the West. Language, distance, and cultural barriers make it difficult for most in the West to access. There have been a few major Western collectors over the years but the emphasis is on “few.” Nor is this material often found in Western libraries and institutional collections for the same reason. Those who collect in this field undoubtedly have a familiarity that most in the West lack and I will certainly admit to being one. It would be impossible for me to explain what is here to those who are familiar with the field, and to those who are not, this is like the blind leading the blind. Consequently, I have done a small amount of looking around to try to provide a brief and inadequate description of the history, and a few poorly described by me specific examples of material offered. Please forgive my ignorance of other cultures typical of so many Americans.

Many in the West are not aware of this, but printing did not originate with Gutenberg. Earlier printing was primarily done with wood blocks, going at least as far back as the eighth century in China. There was even some use of movable type in the centuries before Gutenberg, but this a different procedure when you're using unique characters rather than interchangeable letters. It also used mainly carved wood rather than metal for its movable type though some employed metal. Movable type was used as early as a few centuries before Gutenberg in Korea though little of these printings survives. Even post-Gutenberg, it was rare, employed only by government printing. Movable type printing did not reach Japan until much later – 1593. Even then, it only made its way to Japan after invasions by Japan of Korea and confiscation of government presses.

Movable type printing was popular in Japan from that time to about 1650 when it faded away. Printers found woodblocks easier to use than movable type. It did not return in any kind of frequency until the 19th century.

This leads us to wonder whether Gutenberg really did invent the movable type printing process or simply borrowed it from Asia. The answer is we do not know. There were some mentions of it in Europe earlier but not many, and no indication in the record that Gutenberg had any awareness of it. Certainly, it was the invention of Gutenberg's press that became one of the most significant developments in history. It spread knowledge far and wide through the West, making books and knowledge attainable by so many more people than was possible with manuscripts. In Korea, for certain cultural reasons, it did not spread beyond government use or for ritual purposes rather than for serious reading. Japan was a closed society, so there was no interest in using the process to inform the population about events in the world. Consequently, the invention of movable type was not the momentous development in the East that it was in the West.

Next, we have a few samples of what can be found in this catalogue, admittedly poorly described.

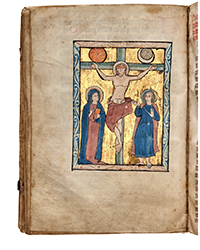

This is an example of early printing that will enable you to put your neighbor who owns a Gutenberg Bible to shame. It comes from Japan and was printed in 1297. This is not a movable type book but one printed from woodblocks. Hill describes this as “extremely rare; this is one of the earliest substantial wood-block printed books created in Japan to survive.” It was printed in Nara at the chief temple of the Kegon sect of Buddhism, founded in 728. This “new technology” was used by the monks to spread their beliefs. The title is Daijo kishinron giki (commentary on the awakening of faith in the Mahayana). Mahayana, to the best of my understanding, is the major branch of Buddhism, and I will leave it at that not being familiar with the tenets of Buddhism. Item 1. Priced at $75,000.

This next book is known as Yunjing in Chinese, Inkyo in Japanese. That translates to “Mirror of Rhymes.” It is a guide to pronunciation, and while this one is dated 1564, it goes back to many centuries earlier. The problem was that over the years, while the Chinese characters remained the same, the pronunciation of them changed in the north and south of China over the years. The same is true of Japan, where the characters are shared but the pronunciations are not. The result is that correct pronunciations depended on where you lived, and other pronunciations were unrecognizable. As Americans know, the English don't speak English properly, but at least we are close enough so that we can communicate. This is because letters, for the most part, have fairly common sounds for both parties, meaning the sounds of words will be reasonably similar. With characters, however, since there are no letter foundations, there is nothing to reveal the proper sound, making pronunciation more difficult to know than with letter-based words. By ordering character-words by sounds and using rhymes to show those sounds, this book filled the pronunciation half of the role of a traditional Western dictionary. Hill notes this is one of the earliest extant copies of a book that preserves the earlier stages of how Chinese sounded. Item 4. $100,000.

This book is the tale of two long-ago wars. The title is Hogen Heiji Monogatari, the Tale of Hogen and the Tale of Heiji. They were fought between the followers of rival clans and leaders. The Hogen Rebellion occurred in 1156, the Heiji Rebellion in 1160. Other than deciding which clan would rule, the wars led to the rise of the Samurai class in Japan. The tales were written some years later in the 13th century, while this apparently unknown variant of this rare book was privately printed with movable type circa 1607-1608. Item 11. $75,000.

Jonathan A. Hill Bookseller may be reached at 646-827-0724 or jonathan@jonathanahill.com. The website is www.jonathanahill.com.