Martayan Lan has issued their Catalogue 50 of Rare Books, Maps & Manuscripts. The catalogue is divided into four sections: travel, science and medicine, arts and humanities, and objects. It is filled with early material, much from the 15th and 16th centuries. It is also a catalogue of important material, rare and often groundbreaking works. This is strictly a selection for those who collect at the highest level. Here are a few examples of what is to be found.

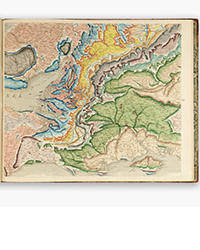

The Age of Discovery quickly led to the age of great atlases. For the first two centuries of that era, by far the best atlases were produced in the Netherlands. The earliest of the Dutch map and atlas makers were Abraham Ortelius and Gerard de Jode. The two began work together, but soon became competitors. From a business standpoint, Ortelius was the winner of that competition, going on to publish many editions of his atlases. De Jode’s atlases were likewise outstanding, but he was not as good at selling them. The result is that there were only two editions of his Speculum Orbis Terre. The first edition was published in 1578, the second in 1593. Item 7 is a copy of that second edition, which was greatly expanded from the first. It contains 109 maps on 83 plates, representing 33 new maps not contained in the first edition. Each is colored in a contemporary hand. The atlas contains two new world maps and new maps of the Americas, including the first separate map of North America found in a standard atlas. Priced at $650,000.

Item 21 is what Martayan Lan describes as a “legendary Brazil rarity,” the first edition of a book that would become extremely popular and later reprinted in a great many editions. It was written by the German adventurer, Hans Staden, first published in the German language in 1587: Warhaftige Historia und beschreibung eyner Landtschafft der Wilden Nacketen, Grimmigen Menschfresser-Leuthen in der Newenwelt America gelegen… (history of the man-eating savages of the New World in America). Staden first sailed for Brazil in 1547, returning a year later. What he learned about local culture would serve him well when he made a return trip in 1549. His ship was wrecked on an island. He was able to make it to the continent, but was captured by the Tupinamba natives, who had a healthy distrust of the foreigner they assumed was Portuguese, their enemy. Staden tried to convince them he was French, but to no avail. He was destined for the cooking pot, or so Staden claimed, but befriended the chief. From there, he served as a translator and interpreter to the tribe, a useful service that preserved his life. He also became something of a seer to the tribe, who believed he must have some mystical, Godly powers. He was unable to win his freedom, but finally managed to escape six years later, hailing a French ship and returning to Europe. His tales of cannibalism made this book a bestseller of its time, though some have later questioned whether Staden exaggerated his account a bit. Price on request.

Next is a major scientific work, particularly for the field of botany: De Plantis… by Andrea Cesalpino. Published in 1583, this book is of major importance as it was the first attempt to create a systematic botany. Prior to De Plantis, botanical books were systemized based on outside factors, plants being organized by such things as alphabetical order or their medicinal properties. Cesalpino classified them based on physical factors and tangible qualities of the plants. Linnaeus’ work several centuries later would follow from the organization Cesalpino began. Item 34 is a copy of the book carrying the provenance of Joachim Camerarius (the Younger), who lived from 1534-1598. Camerarius was a Nuremburg physician and botanist, and he has added many contemporary annotations to the margins. $115,000.

Item 46 is a description of an 18th century mechanical wonder: Mechanismus der menschlichen Sprache nebst Beschreibung einer sprechenden Maschine, published in 1791. It is a talking machine, the creation of inventor Baron Wolfgang von Kempelen. Von Kempelen was best known in his time for the “Turk,” a chess-playing automaton that beat most everyone it played. It consisted of a model of the upper part of a human form, dressed like a Turk, on a cabinet. Von Kempelen would open a door to the cabinet which would reveal a clock like mechanism, but a small though talented chess player would also squeeze inside. Von Kempelen admitted it was an illusion without explaining. However, his talking machine was real, though it only emitted voice-like sounds while operated by a visible human. He was not pretending the machine was initiating the speech. Von Kempelen used bellows to replace the lungs, a reed for vocal chords, a rubber mouth, and such to mimic speech. Alexander Graham Bell was fascinated by von Kempelen’s work, obtaining and translating a copy of it, as he sought means of reproducing vocal sounds. In time, as we know, he succeeded spectacularly. $9,500.