The use of cylinders for recording dates back to 1877 and the invention of the phonograph by Thomas Edison. As the art evolved to higher quality recording, wax cylinders continued to be used primarily for recordings in the field as opposed to the studio. They can only hold up to two minutes per cylinder, but researchers often used them for notes or to preserve voices and stories of people in out of the way locations. However, it does not appear that they were used very often in Africa. A survey done of collections a number of years back only located a handful of such recordings, the oldest being from Tanzania in 1902. Based on the travel dates of Sir Harry Johnston, who made these recordings, the Ugandan cylinders would appear to be older.

Sir Harry Johnston was a British explorer and diplomat of the late 19th, early 20th century. He traveled through much of Africa for the last two decades of the 19th century, starting in Tunisia, but soon thereafter into the regions south of the Sahara. In his exploring days, he hooked up with Henry Stanley in the Congo and explored Mount Kilimanjaro. He became an agent working on behalf of the British South Africa Company, as well as holding various diplomatic posts in Africa. As consul in Mozambique and Central Africa one of his duties was to help subdue the slave trade.

In 1899, he was sent to Uganda as a special commissioner, resigning that office in 1902. It was of this period that Sir Harry's brother wrote, "I think that Harry was the first to record native speech and song on a gramophone. It was easy to get the boisterous Masai to sing and talk into the 'little box,' but when they heard their own voices coming out of it, they turned and fled in consternation at the mocking little devil mimic." He then moved on to Liberia where in 1904 he recorded the voice of President Arthur Barclay, who had emigrated from Barbados. In his West Indian accent, President Barclay repudiates questions about the existence of cannibalism in his country. As was typical of the day of colonialists, Sir Harry believed that Europeans were superior to the "backward" people of Africa, but he was a sympathetic if paternalistic figure, rather than someone looking to subjugate and take advantage of the continent's natives.

What makes these recording even more remarkable is that there are only a handful of such recordings anywhere close in time to them. Cylinders were not used very often in Africa. For example, Sir Harry recorded the songs of the Kru people while in Liberia. After that, no more recordings were made of their songs until around 1929. Only a small number of cylinders of African voices from the early part of the 20th century can be found in collections anywhere.

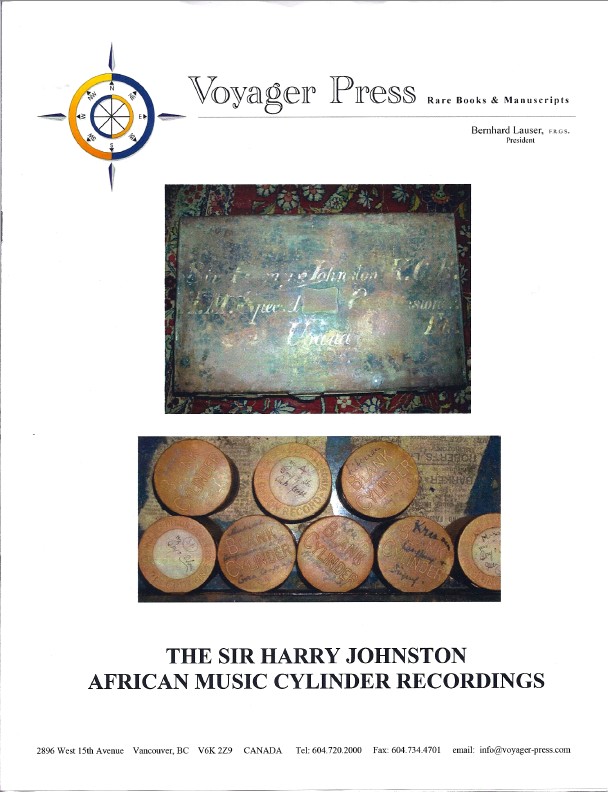

Among the titles found on these cylinders is Kru Language and Broken English, Ashanti Song, Americo-Liberian chorus and solo, Masai Song and Chorus, Masai War Song, Xylophone Music, Speech with Whistles, Liberian Men and Women Talking English, Baganda Song with Flutes, Song of the Suk people, and Christmas Carol by Johnston Family.

After his time in Liberia, Sir Harry returned home to England and did a fair amount of writing in his later years, both novels and accounts of his experiences in Africa. He died in 1927.

The collection of recordings is offered for $75,000. For more information about The Sir Harry Johnston African Music Cylinder Recordings, contact the Voyager Press at 604-720-2000 or info@voyager-press.com.