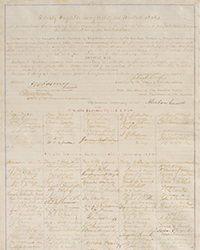

The Raab Collection has issued Catalog 66, a collection of signed documents from important personalities, mostly American. They include leaders from politics, the military, arts, and other fields. Many contain important insights to the views of the people who created the documents. Among the items offered are documents emanating from the most important of American leaders, including Washington, Lincoln, and two Roosevelts. Additionally, there is a long section of documents of lesser significance or cut signatures of important, though not quite so monumental figures. Here, instead of Washington and Lincoln, you can find signatures of Tyler, Fillmore and Pierce. The Raab Collection always provides fascinating material, and detailed descriptions that place the items within their historical context. Here are a few.

That is a most interesting letter you see on the cover of this catalogue. It was written by Orville Wright, one half of the Wright Brothers, to Horace Lytle, owner of a Dayton advertising agency. Lytle, a sportsman, had evidently asked whether the flight of birds had influenced their design of airplanes. Orville Wright responds, to the most part, in the negative. He writes, "I can not think of any part bird flight had in the development of human flight excepting as an inspiration." Wright explains that he and his brother had studied birds for ideas, but never drew much from them, though after the fact they could see how some of the principles they discovered were also employed by birds. The letter was written in 1941, almost four decades after the brothers' famous flight. Item 9. Priced at $17,000.

It is not that well known, but at the outbreak of the Civil War, William Tecumseh Sherman was serving as superintendent of a military college in Louisiana that would later become Louisiana State University. Sherman was an Ohio native, but the Louisiana college had hired him as it wanted someone with a respected military background. In such a situation, you might expect Sherman to have divided loyalties as it became apparent that civil war was inevitable. Sherman suffered no such indecision. He was a Union man all they way and even then called for swift and decisive action against any attempts at secession. In a letter to General Graham, the president of the institution's board of trustees, dated "Christmas 1860," Sherman makes clear that the moment Louisiana secedes from the Union, he will "do no act, breath no words" hostile to the U.S. government. Instead, he will prepare for a successor to replace him at the school. Then, Sherman goes on to opine that President Buchanan made a "fatal mistake" by not reinforcing major Robert Anderson at Fort Moultrie (and nearby Fort Sumter) in Charleston, South Carolina, harbor. This is a telling remark as the Civil War would start a few months later when Confederates attacked Fort Sumter. In words more reminiscent of Presidents Jackson and Taylor, rather than the weak Buchanan, Sherman says the President should have sent 3,000 Union troops to Sumter, which would have held South Carolina in check until "reason could resume its sway." And, in words perhaps prescient of his later March to the Sea, Sherman says of Major Anderson, "Let them hurt a hair of his head in the execution of his duty, and I say Charleston must be blotted from existence." Perhaps if Sherman had been President, there would have been no Civil War, but as we know, Sherman did not want to be President. Sherman's letter is item 13. $17,000.