Like many people in the book business I’ve had good and bad experiences with consignment. Over the years I pretty much avoided this method, but as I got older and my own stock dwindled, I noticed that some of my best transactions involved consignment.

If you’re relatively new in the book trade at some point you will either be asked to take material on consignment, or you will have an individual book or group of items you think could be more profitably sold by someone else; then you’ll start to think about entering into a consignment agreement.

The Agreement

The first step in any consignment deal is the agreement: In my experience that agreement can be simple, or it can be complex; but even for a handshake deal there should be at minimum a written memo that contains a list of what is being consigned, terms on how the proceeds will be split between the parties, a starting and an ending date, and if there is shipping involved, who will pay the costs to return unsold goods. The agreement also usually contains some kind of a liability waiver, saying that the person on the receiving end is not responsible for any damage or loss that may occur and that the consignor is responsible for carrying their own insurance.

Courtesy to the trade:

Courtesy to the trade is a bookseller term indicating that in dealer-to-dealer sales, the seller will give a courtesy discount to the buyer. This discount can be as much as 20%, but some kind of a discount (if asked for) is almost always extended. In consignment sales it is good to decide in advance who is going to absorb the discount or if it will be split.

(See end of this article for a sample consignment agreement supplied by a medium size online bookseller. Notice that in this agreement the split varies depending on the selling price of the book. For the more expensive books the consignor gets a larger share of the proceeds. This is a contract used by one bookseller. It is not an industry wide standard.)

The main advantage of consignment is that seller does not have to pay for the goods until after the material is sold, and if the material consigned is attractive, sometimes it can turn over quite rapidly and be profitable to all parties.

For example, a local client of mine was downsizing his collection in an area that interests me. I was invited to pick out some books and market them. The split was 50/50. I enthusiastically agreed, picked out about 20 items ranging in price from about $100 to about $1,000. We shook hands, and made a short title list that included some notes by my client suggesting (but not requiring) a retail selling price for each item. I boxed them up and sold them all in less than two weeks. There was nothing to return and both sides seemed happy with the results. What not to like about quick and profitable?

Six months later the same client asked if I would be interested in doing more consignment, and not surprisingly I jumped at the chance. But this time I noticed that the remaining stock was not quite as attractive as what I’d seen earlier and, oh yes, there was one little change in how we’d split it. This time the seller wrote down the price of what he’d paid for each item and wanted to make that price back, and anything over that price, then we’d split the that amount 50/50.

As you might imagine, this did not work out quite as well for me as it did for my client.

Because the second lot was less desirable than the prior group they did not sell as well, and my share of what did sell was considerably smaller than it had been previously. While I did not exactly jump for joy at how it turned out, it did bring home to me that a seemingly small modification to the agreement did have a big impact on what I received. Because we were friends, and because I’d done very well the first time, I didn’t grumble about the slender returns on the second go round, but I definitely would not do things that way again.

My other recent experience with consignment is this month. This time I’m the one sending the goods off, in this case a small but expensive art book. I found a reputable dealer who was willing to take my book to one of the big ABAA Mainland shows on consignment under an arrangement we both considered fair. I was very pleased that the dealer was willing to consider my item, and perhaps by the time you read this I’ll know if it sold and at what price.

These few examples involve a small number of items on consignment for a short period of time. However, usually consignment agreements involve much larger numbers of books and last for much longer times, typically from one to two years at minimum.

The deals are more complicated when the numbers get bigger

Talking with several antiquarian booksellers who have done these kinds of deals it’s important to recognize that when you take in a large number of items from someone else’s inventory, and commit to marketing them, you inevitably redirect some of your attention away from your own stock, which you own outright, and focus it on the goods that do not actually belong to you. Not only do you have to split the proceeds, you also have to catalog and track the items and be able to render an accurate financial accounting. These are the kind of deals that can turn into real problems, especially if you don’t have enough staff, or your software doesn’t do a good job of coding and tracking.

In bookselling circles the example of Peter Howard, the famously disorganized owner of Serendipity Books in Berkeley, comes to mind. If we’re talking about consignment deals gone south he is often the case in point. He did consignment deals with dozens, nay hundreds of dealers and collectors, and when he died in 2011 there was often little or no paperwork to support what part of his vast inventory (said to have numbered a million volumes) was actually his and what belonged to others. He left his heirs a major headache, and while I’m told that most of it was eventually sorted out, it is not the kind of problem that most of us would like to face.

As I talked to other booksellers about how they viewed larger consignment transactions they mentioned two main points: 1) they prefer to do business with those they already know, and 2) if they have their heart set on acquiring a certain collection or group of collections, well it can take some time, as in years.

For example: about ten years ago I made a referral to a dealer friend mentioning an academic collection owned by a professor who was retiring. Jump cut to 2023; my friend has just managed to secure a consignment agreement for a portion of the collection, and that is only after buying a significant number of books outright and building a friendly trust relationship with the professor over the course of more than a decade.

The same is true for another well known bookseller who had his eye on a particular collection, and he too, had to wait for more than ten years for the seller to truly decide he was ready to sell.

In this case it was beneficial to both parties because the value of the collection had gone up significantly. It was mostly ephemera and mostly one of a kind and on a topic that had become much more high profile as the years rolled by.

But it works the other way round too. The seller who waits too long to consign may find the market is no longer as interested as it once was, i.e. the value of the collection has gone down.

Almost everyone I spoke with said that when it came to consignments of significant size, dealers preferred to buy it all at a fixed but somewhat lower lot price, rather than take it on consignment.

Reasons included the hassle involved with cataloging, tracking, and returning unsold merchandise. They also noted that in larger deals with often elderly collectors, people die, drop out of sight, fail to notify their heirs of these arrangements and that they can indeed become problems with the passage of time. One dealer told me, “We took a big collection from one guy and then he disappeared. We’re still selling his stuff, but at the moment we have nowhere to send his share of the proceeds.”

The truly game changing consignment deal

And then there are the consignment deals that completely change the nature of your business model. For example there is one Washington state shop that has entered into an agreement with a major metro libraries systems “Friends” group and is now about a year and a half into taking in, sorting, evaluating, cataloging and selling what they estimate to be about 100,000 volumes a year. That number is expected to get bigger going forward. So far the owner says it’s working out well for the Friends group which was severely impacted by the pandemic and could no longer afford to warehouse or bring people together for sales to move the high volume of donations. It’s also working well for the bookseller who is experiencing a quantum leap in volume, even though it has become more complicated to keep track of what can be sold profitably and what should be passed out for free or next to free for the benefit of the public. Altogether he was pretty happy at the arrangement and felt that it had worked out to benefit the library system, his own company and the larger community, but he did mention that it had changed his entire business model and presented considerable challenges to his staff of four.

—------------------------------------ (Sample Consignment Agreement) —--------------------

SAMPLE CONSIGNMENT AGREEMENT provided by a long established online bookseller:

CONSIGNMENT AGREEMENT WITH (NAME OF PARTY ACCEPTING GOODS)

The following terms relate to the consignment agreement between NAME of person consigning book (consignor) and NAME of the firm accepting goods (consignee):

CONSIGNOR agrees to provide books and other book related materials and papers to consignee for purposes of sale, for a minimum of one year. Insurance on these books will remain the responsibility of the consignor, and consignee is not responsible for loss due to theft, or other causes, while in the consignee’s custody or in transit.

CONSIGNEE agrees to:

-

Grade and price books (grading is at the discretion of the consignee, price of books over $1,000 is subject to approval of consignor.)

-

Place books for sale in catalogs, online and at book fairs as appropriate.

-

Provide payment and accounting on a monthly basis to the consignor. Statements will be issued on the 15th of the month following the sale of the book(s).

Both CONSIGNOR and CONSIGNEE agree that the price paid to the consignor will be on the following schedule:

-

75% of net sales price for books selling for more than $500.00

-

70% of net sales price for books selling between $200.01 and 500.00.

-

60% of net sales price for books selling between 100.01 and 200.00

-

50% of net sales price for books selling at $100.00 or less.

-

Consignee may provide up to a 20% discount, at consignee’s discretion and the discounted price will be the sales price. The amount due will be based on the net price after deducting any commissions, selling fees and other expenses.

-

Consignee is in no way responsible for whether or not the books sell, nor to whom they may be sold.

-

Either party may terminate this agreement at the end of one year, or sooner by mutual agreement.

-

Signature of both parties below amounts to agreement with the terms above.

-

X________________Consignor X_____________________Consignee (Date)

BOOKS CONSIGNED (see attached list) End sample agreement.

Reach RBH writer Susan Halas at wailukusue@gmail.com

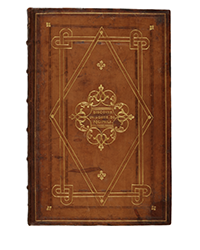

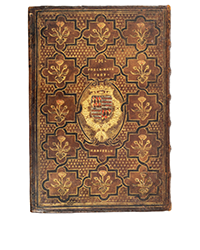

![<b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633. <b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/8caddaea-4c1f-47a7-9455-62f53af36e3f.jpg)

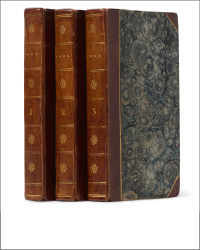

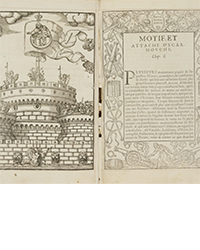

![<b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 16:</b> [Austen, Jane]. A handsome first edition of <i>Sense and Sensibility,</i> the author's first novel. $60,000 to $80,000. <b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 16:</b> [Austen, Jane]. A handsome first edition of <i>Sense and Sensibility,</i> the author's first novel. $60,000 to $80,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/9a74d9ff-42dd-46a1-8bb2-b636c4cec796.png)