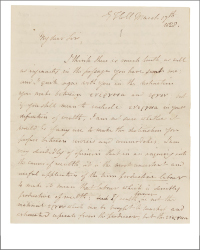

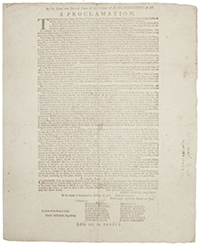

This story goes back to the early days of America, before there even was a United States. It concerns a letter written in 1780 during the Revolutionary War. It was sent by one of America's founders and patriots to another. The letter was a warning issued to embattled American and French forces defending the newly declared independent nation from attack by British forces intent on putting all this nonsense to an end.

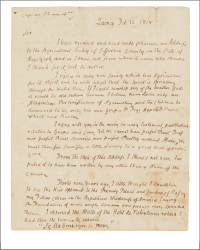

The letter was written on July 21, 1780, by Alexander Hamilton from Preakness, New Jersey, to the Marquis de Lafayette, in Danbury, Connecticut. Writes Hamilton,

“My Dear Marquis

We have just received advice from New York through different channels that the enemy are making an embarkation with which they menace the French fleet and army. Fifty transports are said to have gone up the Sound to take in troops and proceed directly to Rhode Island.

The General is absent and may not return before evening. Though this may be only a demonstration yet as it may be serious, I think it best to forward it without waiting the Generals return.

We have different accounts from New York of an action in the West Indies in which the English lost several ships. I am inclined to credit them.

I am My Dear Marquis with the truest affection Yr. Most Obedt

A Hamilton Aide De Camp”

We presume that the “Sound” mentioned is Long Island Sound, and the “General” is General George Washington.

When Lafayette received the letter, he immediately gave it to Massachusetts General William Heath, who forwarded it on to the President of the Massachusetts Council, with a letter of his own summarizing its meaning. The Council received the letter on July 26 and immediately recognized the threat, quickly sending Massachusetts forces to Rhode Island to assist the French. We now know it all turned out fine, at least from the American point of view.

Hamilton's letter, along with that of Heath and other documents from the period, were later transferred to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. From there, they made their way to the state Archives. In the mid-19th century, Hamilton's letter, along with Heath's, were listed in an index of the Archive's holdings. Hamilton's letter again appears in an index of the Archives in the 1880s, and a photostatic copy was bound into the index in the 1920s. Photostats were a type of early photographic copies invented in the first decade of the twentieth century, meaning Lafayette's letter was still in the possession of the Archives in the new century, and likely the 1920s when it was bound in to the index.

In the 1950s, the Archives undertook a compilation of Hamilton's material. It was then noticed that the letter was missing. It had disappeared during the approximately 30-year period since the 1920s.

It next appears at the Potomac Company auctions in Virginia in 2018. It was brought there by Stewart R. Crane for sale. The Potomac Company did its due diligence and discovered the letter was missing from the Massachusetts Archives. They called in the FBI. The FBI obtained a warrant and seized it. That led to an action by Crane, who was replaced by his estate in the action as he died shortly thereafter.

The Crane estate and the Archives offered differing theories of how the letter got to him. Crane inherited the letter from his grandfather, Stewart Crane. The estate provided an account of how his grandfather came into its possession in, what the Court described, as “a reconstruction not burdened with many hard facts.” You can see where this is going. They said the elder Crane purchased it “in good faith” in 1945 from John Heise Autographs, “a reputable rare documents dealer in Syracuse, New York.” Not surprisingly, they could not provide much proof of this as it all happened 70 years ago by a person no longer living. All the estate could proffer was was an affidavit recounting the verbal family history and an empty envelope from Heise to R. E. Crane postmarked 1945.

The government had a different explanation. They said the letter was stolen by Harold E. Perry, a “kleptomaniacal cataloguer” who worked at the Archives from 1938-1945 or 1946. He had extensive access to the collections and absconded with numerous historical documents, some of which he hoarded in his home and others of which he sold to disreputable dealers. The Court offered no opinion on which theory was correct as there was no need. The case was decided on other grounds.

The government responded that Crane had no standing to bring the suit. The concept of standing means you have to have some interest in a case to sue or participate in it. While family possession for 75 years might seem to be enough to show an interest, the government countered that by law, no one but Massachusetts could own the document, so no one else could possibly have standing to sue for it. That argument carried the day. Going back to 1897, Massachusetts has had a law that says public records held by the state cannot be alienated, that is, sold or otherwise disposed of. Historic documents from before 1800 are unquestionably going to be considered protected public documents. The index records established that they were in the possession of the commonwealth after the law of 1897 was passed. Therefore, no one but Massachusetts had a legal right to this letter. It doesn't matter how it got to the Cranes, sold, stolen, thrown away. It was and can only be the property of Massachusetts. Case closed. There is nothing more to say, so there is no reason for the estate to waste the court's time any longer.

And so, the letter has been returned to the Massachusetts Archives. It has now gone on display at the Commonwealth Museum.

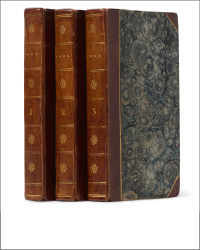

![<b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 16:</b> [Austen, Jane]. A handsome first edition of <i>Sense and Sensibility,</i> the author's first novel. $60,000 to $80,000. <b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 16:</b> [Austen, Jane]. A handsome first edition of <i>Sense and Sensibility,</i> the author's first novel. $60,000 to $80,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/9a74d9ff-42dd-46a1-8bb2-b636c4cec796.png)

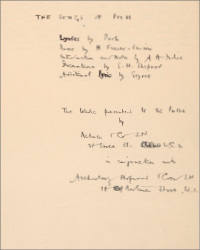

![<b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633. <b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/8caddaea-4c1f-47a7-9455-62f53af36e3f.jpg)