Christopher Coover recently passed away, leaving a remarkable history with Christie’s, richly detailed in the many important sales he catalogued as a team member. Collections and collectors tend to be remembered while the folks with the green eyeshades who confirm, and describe material for consignors, are only rarely in the spotlight. Mr. Coover, who joined Christie’s in 1980, would become a widely acknowledged expert in the collectible paper field during his 35 year career with them.

His tenure almost precisely bridged two tectonic shifts in the rare book auction field, the first in 1980-2 when Sotheby’s and Christie’s began to reorient their cataloguing to the retail bidder, and the other, when the Internet made cataloguing easier in the late 1990’s. Before 1980, dealers were the principal buyers at auction and were expected to understand the what, why and wherefores. The new cataloguing would embrace the challenge to educate new bidders, starting the trend to provide increasingly complex dissertations, broadening the audience and raising prices. It’s now well established, to the point that in 2021, it became the first year to see total realizations at auction for books, manuscripts, maps and ephemera reach a billion dollars. Mr. Coover’s approach and his excellence in cataloguing in Americana developed over four decades, today finds evidence of his impact on the writing and researching important catalogues worldwide every day.

Chris’s history at Christie’s in New York began when Stephen C. Massey hired him in 1980 to join the Book Department alongside Bart Auerbach. Soon after a brief interlude with John Fleming, he would return and remain at Christie’s until his retirement in 2016 as Senior Vice President.

Over his career he assisted with and contributed insights about many of the icons of printed and manuscript history. The Codex Hammer, a Leonardo manuscript, sold for $30.2 million in 1994 was one example.

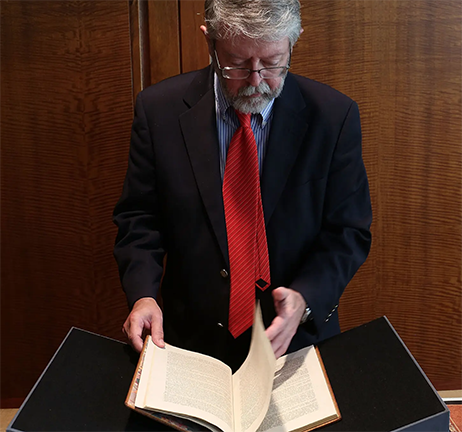

In an 2011 interview with the Colonial Williamsburg Journal, he explained his work as, authenticating material offered for auction, describing its provenance and history for the auction catalogue, and then suggesting the opening price. Contextualizing material was his art.

Many concur that his descriptions for the Forbes sales in the first years of the 21st century were his finest work. Forbes’ material was acquired when the descriptions were much sparser. In Mr. Coover’s hands decades later, he re-introduced the same items as remarkable survivals, explaining their significance. In 6 sales, between 2002 and 2007, a small group of collectors and sundry bidders paid $40.9 million. The first sale, on March 27, 2002, was the most spectacular, with 203 lots bringing $20,069,990. The second, on Oct. 9, 2002, with 232 lots, brought $9,366,000.

As a bidder Seth Kaller bought nearly 100 of those lots in the first 2 Forbes sales, and recently pointed out that at least 80 of them have since been donated to the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History - whose programs now use those documents in more than 30,000 schools. According to Kaller, Chris made it easy to get an idea of what really was in the letters and documents being offered, as opposed to just providing bibliographical and background information.

As a fellow warrior who would prepare auctions, Selby Kiffer, took a part-time summer job at Sotheby’s in 1984 and is today their International Senior Specialist for Books and Manuscripts. And now remembers first meeting Chris in 1982, when they were both taking classes at Columbia’s Dewey School of Library Service with the redoubtable Terry Belanger. “He was already working at Christie’s —I remember visiting him when Christie’s was on Park Avenue—while I was preparing to be an academic rare book librarian. We hit it off and we and our wives socialized for a time,” Kiffer recalled. “Once I started working at Sotheby’s, it became difficult to maintain a close friendship, but although we were often competitors, we always maintained a mutual respect. Certainly, for my part, I recognized Chris as a knowledgeable and passionate specialist.”

Auction history tends to remember highest prices but his broad interest in context transforming documents into pieces of historical puzzles may well be his greatest contribution to the field. Today, that approach is today the norm.

And while he will be principally remembered as discoverer and explicator of important documents, he was a collector himself of musical manuscripts and a regular on the Antiques Roadshow.

Stephen Massey describes him as “a cornerstone figure.” A signal figure in the history of auction cataloguing.

And it turns out he not only made discoveries he also made many friends.

He made a difference and left his mark.

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> ROALD AMUNDSEN: «Sydpolen» [ The South Pole] 1912. First edition in jackets and publisher's slip case. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> ROALD AMUNDSEN: «Sydpolen» [ The South Pole] 1912. First edition in jackets and publisher's slip case.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/0a99416d-9c0f-4fa3-afdd-7532ca8a2b2c.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> AMUNDSEN & NANSEN: «Fram over Polhavet» [Farthest North] 1897. AMUNDSEN's COPY! <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> AMUNDSEN & NANSEN: «Fram over Polhavet» [Farthest North] 1897. AMUNDSEN's COPY!](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/a077b4a5-0477-4c47-9847-0158cf045843.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> ERNEST SHACKLETON [ed.]: «Aurora Australis» 1908. First edition. The NORWAY COPY. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> ERNEST SHACKLETON [ed.]: «Aurora Australis» 1908. First edition. The NORWAY COPY.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/6363a735-e622-4d0a-852e-07cef58eccbe.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> SHACKLETON, BERNACCHI, CHERRY-GARRARD [ed.]: «The South Polar Times» I-III, 1902-1911. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> SHACKLETON, BERNACCHI, CHERRY-GARRARD [ed.]: «The South Polar Times» I-III, 1902-1911.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/3ee16d5b-a2ec-4c03-aeb6-aa3fcfec3a5e.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> [WILLEM BARENTSZ & HENRY HUDSON] - SAEGHMAN: «Verhael van de vier eerste schip-vaerden […]», 1663. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> [WILLEM BARENTSZ & HENRY HUDSON] - SAEGHMAN: «Verhael van de vier eerste schip-vaerden […]», 1663.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/d5f50485-7faa-423f-af0c-803b964dd2ba.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> TERRA NOVA EXPEDITION | LIEUTENANT HENRY ROBERTSON BOWERS: «At the South Pole.», Gelatin Silver Print. [10¾ x 15in. (27.2 x 38.1cm.) ]. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> TERRA NOVA EXPEDITION | LIEUTENANT HENRY ROBERTSON BOWERS: «At the South Pole.», Gelatin Silver Print. [10¾ x 15in. (27.2 x 38.1cm.) ].](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/fb024365-7d7a-4510-9859-9d26b5c266cf.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> PAUL GAIMARD: «Voyage de la Commision scientific du Nord, en Scandinavie, […]», c. 1842-46. ONLY HAND COLOURED COPY KNOWN WITH TWO ORIGINAL PAINTINGS BY BIARD. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> PAUL GAIMARD: «Voyage de la Commision scientific du Nord, en Scandinavie, […]», c. 1842-46. ONLY HAND COLOURED COPY KNOWN WITH TWO ORIGINAL PAINTINGS BY BIARD.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/a7c0eda0-9d8b-43ac-a504-58923308d5a4.jpg)

![<b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 11:</b> Darwin and Wallace. On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties..., [in:] <i>Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnean Society,</i> Vol. III, No. 9., 1858, Darwin announces the theory of natural selection. £100,000 to £150,000. <b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 11:</b> Darwin and Wallace. On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties..., [in:] <i>Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnean Society,</i> Vol. III, No. 9., 1858, Darwin announces the theory of natural selection. £100,000 to £150,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/00d5fd41-2542-4a80-b119-4886d4b9925f.png)