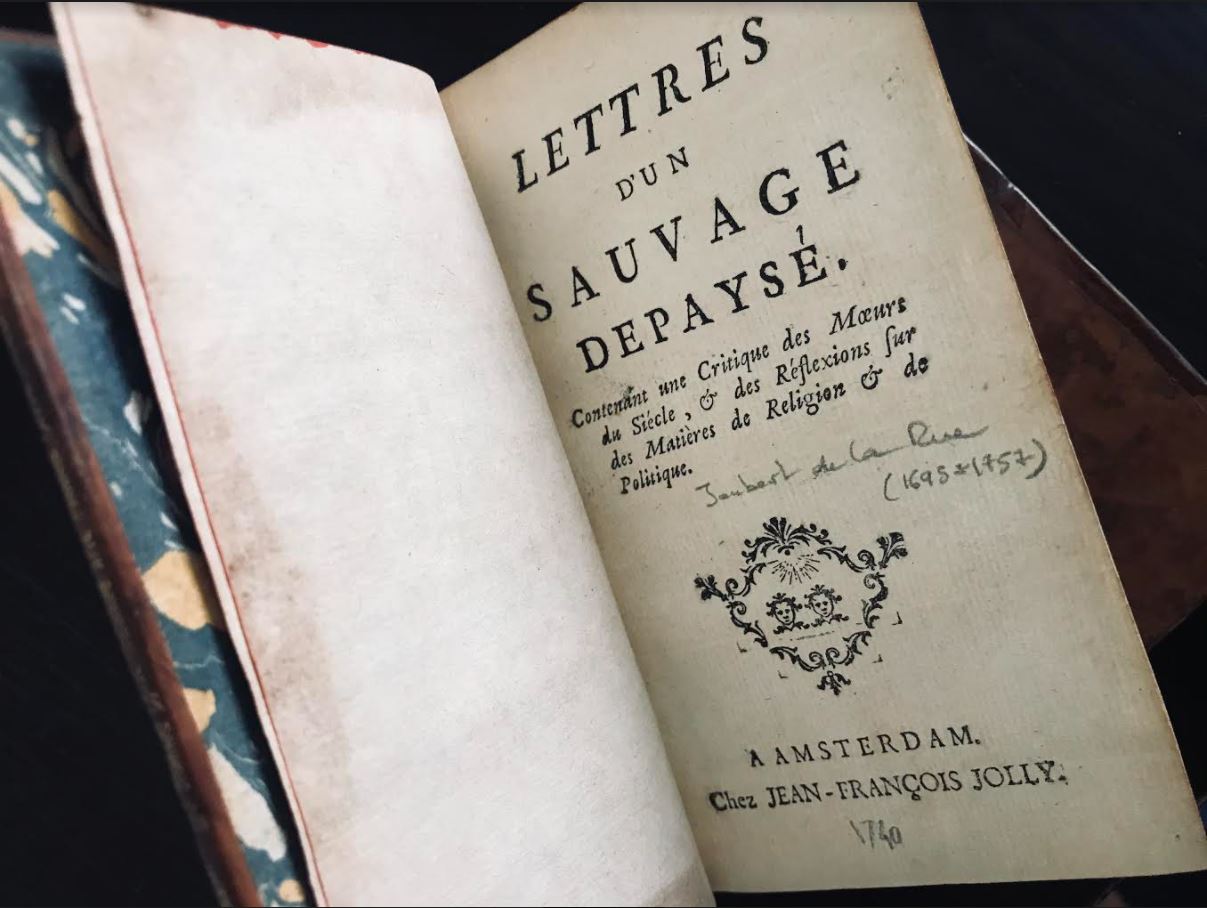

In the wake of Montesquieu’s Lettres Persanes (1721), fake epistolary works from alleged travellers became a sure way to draw a satirical portrait of society. Thus, while pretending to be an American ‘savage’ passing through France, François Joubert de la Rue (1695- circa 1757) was actually a French protestant in exile. And he wrote some letters to a fictitious friend in America that were soon compiled into a book, Lettres d’un Sauvage Dépaysé (Amsterdam, 1740)*.

This a 2 in-18 volume-set book printed by Jean-François Jolly in Amsterdam in 1740 with an explicit subtitle: Containing A Critic of the Customs of the Time, and Some Reflexions over Political and Religious Matters. Those 30 letters originally came out separately between January and April 1738 under the title of Letters From A Homesick Savage To His Correspondent in America. Like most epistolary satires, this is a pleasant read—a good format, a smooth narrative and a variety of topics make it entertaining. Joubert apposes the “Savage Reason” to the “Civilized Reason” to cast a critical look at French society.

A Matter of Honour

Native Americans were considered as ‘Savages’ yet Joubert underlines that the “point d’honneur/matter of honour’ that ruled relationships in Europe sometimes bordered on savagery. A true gentleman couldn’t stand the slightest offense, be it ridiculous and coming from an uneducated fool. “If you ever come across a man who pretends he once saw a cauliflower big enough to feed an army of 100,000 men,” Joubert writes, “you must not deny the fact (...); or you’ll hurt his honour.” Or else, be ready to potentially die over the size of a cauliflower, because if you contradict him, he is then entitled to challenge you to a deadly duel—a radical way to reasonably settle a vegetable quarrel. “If you’re victorious, the crown of glory awaits you,” Joubert resumes.” But you have to run away first, or else you’re lost. Caught before receiving a “Letter From Grace”, you’d be hanged like a petty thief.” In Europe, being civilized could lead you straight to the gallows.

Soldiers

Native Americans didn’t know much about the art of war before the civilized Europeans came in. They were fighting with their hearts, but without discipline—most of the time, the Europeans defeated them quite easily because they knew about civilized war. In Letter XII, Joubert gives more details: “During the summer, the soldiers go to war. They then enjoy having their arms and legs broken, or they break others’. When it’s over, they go back home to enjoy winter pleasures—as most of them are bachelors, they use others’ wives and daughters to make more legs and arms than they have broken during the summer—thus nothing is lost. We saw them more than once comforting a crying mother who blamed them for the loss of her son—and then making her two kids at once, to compensate her.” Europeans had manners, and that makes a huge difference.

Religion

Of course, Joubert’s main target was Catholicism. As soon as Letter II, he tackles the Church. “To be happy, one must teach about what eyes can’t see, what ears can’t hear and what is not yet into the hearts of men. That’s how the servants of the wretch who died on a cross now stand in the very place of the Caesars.” Among the most crucial debates kindled by the discovery of America was the fact that the Bible doesn’t mention this continent or the ‘Savages’ who populated it. How come? Was the Bible fallible? That couldn’t be, unless “the God of Europe has so far created men in America with the sole purpose of plunging them into a bottomless pit of misery.” How could a ‘civilized God’ act so partially? “Because we deserve it,” Joubert states, “since a man ate an apple 5 or 6,000 years ago in Asia.” A Protestant, Joubert then laughs at one of the foundations of Catholicism, that is to say priestly celibacy: “The ‘Civilized Reason’, always fertile in extraordinary discoveries, found out that celibacy was saner than marriage, and that the Creator had made a gross error when he said: “It is not good that the man should be alone; I will make him a helper fit for him.” Joubert describes the sad condition of women who embrace religion—he compares them to the antique vestals, unable to drastically respect a vow that they only reluctantly took since, he adds, many “were forced to become religious in order to discharge their families.” And when the law of nature caught up on them, they “have to cover their horrid fault with horrid deeds—many small skeletons are found in the backyards of convents.” Savagery is never far.

Talking about Joubert’s book, Robert Granderoute also notes (Dictionnaire des Journalistes) “some virulent critics of Catholic dogmas (transubstantiation), institutions (from the papacy to the monasteries), practices and ceremonies, subtleties of the scholastic reason, violences against the heretics, or internal feuds (between the Jesuits and the Jansenists).” In France, L’Observateur Littéraire blamed Joubert’s work for its “furious attacks on religion”; for a while, it was attributed to Marquis d’Argens, another satirical writer, who strongly denied it: “Only a fool, or someone trying to discredit me would dare attributing to me such a book,” he stated. The book sold well, and “eight years later, Joubert de La Rue came back to it, publishing his Letters From The Civilized Savage to Follow Up Those From the Homesick Savage,” the Dictionnaire des Journalistes reads. “They were announced on August 9, 1746 by the Amsterdam Gazette.” At the end of the first letter, we can read: “At Amsterdam, At Jean Joubert’s, bookseller in St Lucy-Steeg, 1746.” And above this inscription: “These letters shall be published every Thursday.” They were later compiled in a book as well, and this one seems to be rarer than the previous one.

Joubert’s letters enjoyed a small success, but are totally forgotten today—they sank into the shadow of Montesquieu’s Lettres Persanes. Yet, they offer another perspective on French society. That’s what satires are all about, to bring the masks down. They make you laugh to make the varnish layer crack; and then is revealed the true savage side of man—and this is always the same ugly face—yours and mine; and the place you live or the God that you pray to just make no difference.

* Lettres d’un Sauvage Dépaysé (Amsterdam, Chez Jean-François Joly). No date. No name. / 2 in-18° volumes: 1) Title-page, 205 pages. 2) Title-page, 220 pages. No illustration.

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> ROALD AMUNDSEN: «Sydpolen» [ The South Pole] 1912. First edition in jackets and publisher's slip case. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> ROALD AMUNDSEN: «Sydpolen» [ The South Pole] 1912. First edition in jackets and publisher's slip case.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/0a99416d-9c0f-4fa3-afdd-7532ca8a2b2c.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> AMUNDSEN & NANSEN: «Fram over Polhavet» [Farthest North] 1897. AMUNDSEN's COPY! <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> AMUNDSEN & NANSEN: «Fram over Polhavet» [Farthest North] 1897. AMUNDSEN's COPY!](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/a077b4a5-0477-4c47-9847-0158cf045843.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> ERNEST SHACKLETON [ed.]: «Aurora Australis» 1908. First edition. The NORWAY COPY. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> ERNEST SHACKLETON [ed.]: «Aurora Australis» 1908. First edition. The NORWAY COPY.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/6363a735-e622-4d0a-852e-07cef58eccbe.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> SHACKLETON, BERNACCHI, CHERRY-GARRARD [ed.]: «The South Polar Times» I-III, 1902-1911. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> SHACKLETON, BERNACCHI, CHERRY-GARRARD [ed.]: «The South Polar Times» I-III, 1902-1911.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/3ee16d5b-a2ec-4c03-aeb6-aa3fcfec3a5e.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> [WILLEM BARENTSZ & HENRY HUDSON] - SAEGHMAN: «Verhael van de vier eerste schip-vaerden […]», 1663. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> [WILLEM BARENTSZ & HENRY HUDSON] - SAEGHMAN: «Verhael van de vier eerste schip-vaerden […]», 1663.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/d5f50485-7faa-423f-af0c-803b964dd2ba.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> TERRA NOVA EXPEDITION | LIEUTENANT HENRY ROBERTSON BOWERS: «At the South Pole.», Gelatin Silver Print. [10¾ x 15in. (27.2 x 38.1cm.) ]. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> TERRA NOVA EXPEDITION | LIEUTENANT HENRY ROBERTSON BOWERS: «At the South Pole.», Gelatin Silver Print. [10¾ x 15in. (27.2 x 38.1cm.) ].](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/fb024365-7d7a-4510-9859-9d26b5c266cf.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> PAUL GAIMARD: «Voyage de la Commision scientific du Nord, en Scandinavie, […]», c. 1842-46. ONLY HAND COLOURED COPY KNOWN WITH TWO ORIGINAL PAINTINGS BY BIARD. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> PAUL GAIMARD: «Voyage de la Commision scientific du Nord, en Scandinavie, […]», c. 1842-46. ONLY HAND COLOURED COPY KNOWN WITH TWO ORIGINAL PAINTINGS BY BIARD.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/a7c0eda0-9d8b-43ac-a504-58923308d5a4.jpg)

![<b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 11:</b> Darwin and Wallace. On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties..., [in:] <i>Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnean Society,</i> Vol. III, No. 9., 1858, Darwin announces the theory of natural selection. £100,000 to £150,000. <b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 11:</b> Darwin and Wallace. On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties..., [in:] <i>Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnean Society,</i> Vol. III, No. 9., 1858, Darwin announces the theory of natural selection. £100,000 to £150,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/00d5fd41-2542-4a80-b119-4886d4b9925f.png)