At last, the code to the mysterious Voynich Manuscript has been broken. Stop me if you've heard this before. Many have tried to break this code, almost as many have claimed to, and yet the language of this extraordinary ancient document has remained unknown. Has the mystery finally been unraveled?

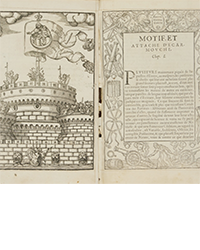

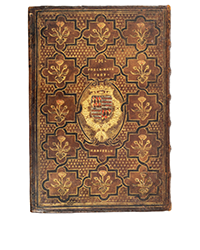

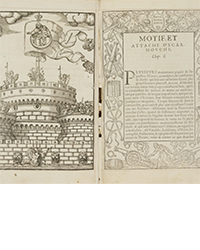

For those unfamiliar with the Voynich Manuscript, it is this beautifully illustrated document, written on vellum produced in the 15th century. The vellum has been carbon dated to 1403-1438. The manuscript depicts mainly plants, baths, and naked women. It is generally believed to be authentic, though some think it was created perhaps a century later in date. It is not thought to be some sort of forgery. Nonetheless, though written in some language, with recurring patterns, no one has yet been able to identify the language or produce a translation.

The Voynich Manuscript is named for Wilfred Voynich, an early twentieth century Polish bookseller. Obviously, he is not its creator, but he purchased it in 1912. Voynich did not sell the manuscript, but his widow later did, to New York dealer H. P. Kraus. Kraus gave the manuscript to the Yale University Library in 1969 where it remains today.

Some have tried to interpret the manuscript based on the illustrations, even if the language is indecipherable. One far-out theory is that it was produced in South America by a sect that escaped persecution in Europe pre-Columbus. That is based on perceived similarities between illustrated plants and those found in America. Another is that it is an herbal, a self-created physician's journal from the 15th century to be used in curing his patients. Others have tried to identify the manuscript based on perceived similarities to European languages, but those similarities have never been sufficient to provide a translation.

A year ago, Dr. Gerard Cheshire, associated with Bristol University, declared he had cracked the code in two weeks time. His theory was that it was in a proto-Romance language, compiled by Dominican nuns for Maria of Castile. The university announced that the code had been broken, but the following day retracted the claim, saying it was not so sure. I haven't seen any follow-ups on the theory since, though perhaps it is because a translation has not quite been completed. These are just some of the recent claims. Attempts to decipher the language go back to Voynich's time, and even World War II code breakers took a shot at it without success. So have some supercomputers.

So now stepping into the fray is Egyptologist Dr. Rainier Hannig, associated with the Roemer and Pelizaeus Museum in Germany. By examining the letters, he concluded that it was written in a Semitic language, Hebrew, Aramaic or Arabic. After further study (he has been working on this since 2017), Dr. Hannig concluded it is based on Hebrew. Hebrew was a language known to scholars in Europe at the time the manuscript was produced. However, it is not Hebrew lettering that can be read by someone familiar with the language or it would have been deciphered years ago. It must be some sort of derivation.

One thing Dr. Hannig's “translation” has in common with all the previous “translations” is that he has not actually translated the manuscript yet. He says it will take some diligent scholars and lots of work to actually produce a translation. None of the theories has actually enabled us to read the document. That would seem to be a basic requirement before we can conclude that Dr. Hannig or any of his precursors (or those that will inevitably follow) have actually broken the code. The proof is in the translation. Until then, we will skeptically withhold judgment.

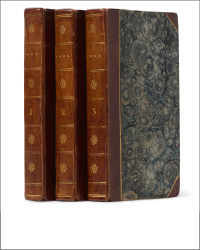

![<b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 16:</b> [Austen, Jane]. A handsome first edition of <i>Sense and Sensibility,</i> the author's first novel. $60,000 to $80,000. <b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 16:</b> [Austen, Jane]. A handsome first edition of <i>Sense and Sensibility,</i> the author's first novel. $60,000 to $80,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/9a74d9ff-42dd-46a1-8bb2-b636c4cec796.png)

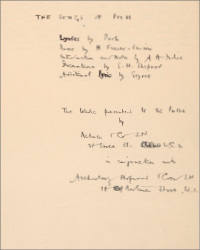

![<b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633. <b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/8caddaea-4c1f-47a7-9455-62f53af36e3f.jpg)