Last month we wrote about a contentious dispute between the Internet Archive and four large book publishers over the use of digitized copies of printed books (click here). The Internet Archive holds over a million digitized copies of printed books in its Open Library. They make these digital copies available for electronic “loan” to patrons, but only in the number of physical copies they actually possess. If the Open Library owns only one copy, patrons can only borrow one copy at a time.

A library may lend a copy of physical books in its possession without violating copyright law under something known as the “First-Sale Doctrine.” It says that as long as you own a book, you may do what you please with it (short of copying it) without making further payments to the publisher or author. However, copyright law provides, with certain exceptions, that you may not copy a book in your possession and sell or lend that copy to someone else. The publishers argue that this is what the Internet Archive is doing when it lends a digital copy of a book they possess. The Internet Archive argues that they are, in effect, lending the physical copy, just in a form consistent with modern technology. Instead of lending the physical copy, they are lending a facsimile, while keeping the physical copy locked away in their inventory so that only one copy is ever actually lent.

The Internet Archive really upset the publishers when they opened something they called the National Emergency Library in response to the novel coronavirus pandemic. Since most regular libraries were closed and could not lend out their physical books, the Internet Archive made more copies available to the public then they possessed. This led to the publishers suing the Internet Archive, which quickly closed down their National Emergency Library. However, the question remaining to be resolved is whether it is legal to lend out a digital copy of a physical book instead of the book itself, so long as you lend out no more copies than you own. This is an issue of enormous significance to libraries and patrons going forward as readers and researchers look more to digital resources for their information rather than visiting numerous libraries personally. The coronavirus has only accelerated the rate of change. This is especially important for rare and obscure books still under copyright for which the nearest library may be a thousand miles away, or in another country.

While the publishers have been battling the Internet Archive over the principle of whether lending digitized copies of your physical books violates copyright law, the same thing has been going on in a more reserved, less public place. The HathiTrust has been doing the same thing, but only as an emergency measure while libraries are closed or limited by the pandemic. They have stuck to a limit based on physical copies, and plan to stop even that when the crisis is over, but the principle is still the same.

For those unfamiliar with the HathiTrust, it is a consortium of university libraries that loaned their books to Google to scan for Google Books. Part of the libraries' deal with Google was not only would Google do the scanning of their books, but that Google would provide them with a copy of their scans. The libraries then combined forces to put each of their sets of scans into one cooperative digital library, known as the HathiTrust. Like Google, they normally only provide access to books that are out of copyright protection. However, during the pandemic, they are now making digital copies of in-copyright books available.

This is how it works. Unlike their out-of-copyright books, you can't access these digital books directly from the HathiTrust website. You can only get it from a member university library. Only U.S. academic libraries that have experienced “an unexpected or involuntary, temporary disruption to normal operations, requiring the library to be closed to the public, or otherwise to have restricted print collection access services,” may participate. And, only students, faculty and staff may borrow these digitized books.

Unlike the Internet Archive, the HathiTrust has no physical books in its possession. Therefore, the determination of whether a library possesses a physical copy depends on each library's collection. Using each member library's inventory records, the HathiTrust determines whether a library possesses a physical copy, and only lets those libraries possessing that book lend a copy of it. If Yale has a copy of a particular book, but Harvard does not, Yale can lend a digitized copy of it from HathiTrust's database, but Harvard may not.

What HathiTrust has done is evidently less offensive to the publishers than what the Internet Archive did. They never lent more books than their members own physical copies, and even that will have a limited duration. The Internet Archive also appears to have more relatively recent books in its collection, perhaps 10-20 years old instead of 50. Nevertheless, the same principle is at play here. Is there a right to turn a physical copy into an equal number of digital copies without violating copyright law? While publishers and authors should have a right to protect their sales of recent and other books still readily salable, the extremely long copyright protection period (95 years) means obscure books, long out of print, are virtually unobtainable by the public. Good luck finding a 70, 80, 90-year old book that hasn't been in print for almost that long at a local library, or just about any library. Copyrights should protect authors, but not block the public's access to knowledge.

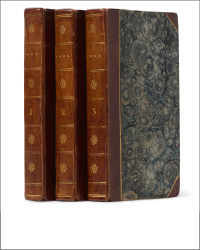

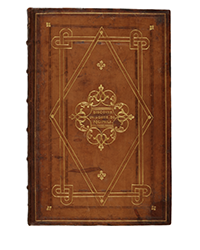

![<b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 16:</b> [Austen, Jane]. A handsome first edition of <i>Sense and Sensibility,</i> the author's first novel. $60,000 to $80,000. <b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 16:</b> [Austen, Jane]. A handsome first edition of <i>Sense and Sensibility,</i> the author's first novel. $60,000 to $80,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/9a74d9ff-42dd-46a1-8bb2-b636c4cec796.png)

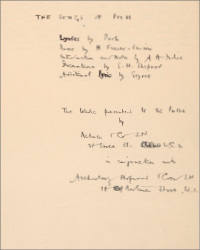

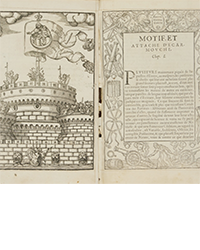

![<b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633. <b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/8caddaea-4c1f-47a7-9455-62f53af36e3f.jpg)