When was America great? Maybe in its infancy, just after the glorious War of Independence? Wasn’t it then a promising land of freedom and opportunity? A New Jerusalem, and a shelter for those who lived in poverty in Europe. In 1795, the young Irish Isaac Weld (1774-1856) went there to find out for himself. He came back after a three years’ tour that took him from Philadelphia to Washington to Canada, and he published his journal, Travels Through the States of North America and the Provinces of Upper and Lower Canada During the Years 1795, 1796 and 1797 (London, 1799). His last words are: “I shall speedily make my departure from this continent (...) without a sigh, and without entertaining the slightest wish to revisit it.” As if he had foreseen, the evils are still at work 220 years later.

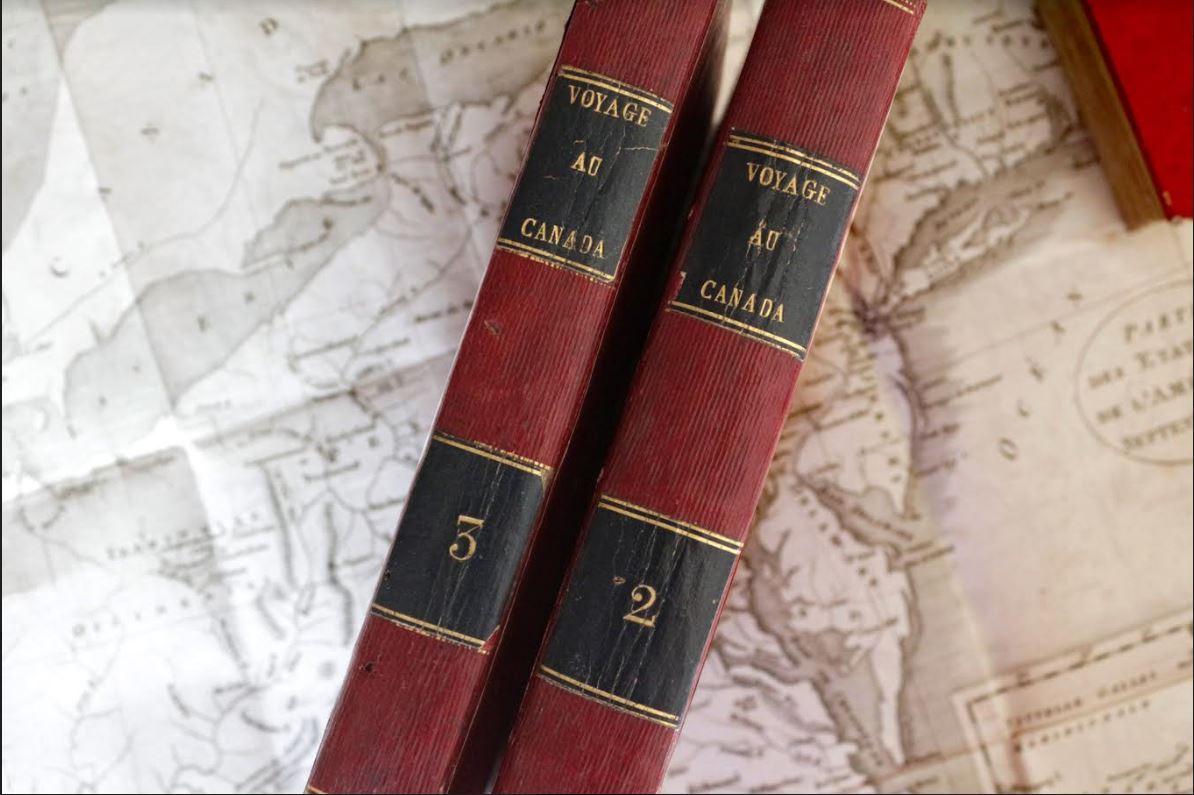

I recently came across a copy of the French translation of Weld’s relation, Voyage au Canada, dans les années 1795, 1796 et 1797 (Paris, chez Gérard—XI/1803)—the first French edition came out in 1800. Our copy is a three in-8° volume set, complete with a gorgeous folding map and 11 full-page engravings. “The author explains (...) that he went there to see whether the various reports telling us of how happy and flourishing this country is were accurate or not,” the French publisher writes. America was quite fashionable at the time as the war of Independence (1775-1783) had had a tremendous impact in Europe, and especially in France (the French troops had sided the Americans against the English)—the birth of this new and formidable nation was a fascinating event. Would America be a New Jerusalem where Man could redeem himself and start anew? Isaac Weld wanted to see it with his own two eyes, and he was disappointed. Interestingly enough, the evils he points out in 1795 are almost the same that American society has to cope with today.

In Money We Trust

Travelling in America at the time meant sleeping in scattered inns along the way, and meeting ordinary people. And Weld wasn’t much impressed with the “American way of life.” “I hardly know whether to ascribe to their love of making money, or to their real indifference about fare; (...) certain it is, however, that their mode of living is most wretched.” In those inns, people were kind of rude—and not even money could help it. “The people will pocket your money with the utmost readiness, though without thanking you for it. Of all beings on the earth,” Weld writes, “Americans are the most interested and covetous.” Here, the French edition adds: “And politeness is unknown to them.” Weld also portrays those he meets as generally ignorant and prompt to quarrel over politics, or anything else. He is also surprised at the scarcity of food, which he blames on the farmers’ “desire of making money.” Americans, he adds, are ready to suffer any inconvenience to make more profits. “If he has built a confortable house for himself, he readily quits it, as soon as finished, for money, and goes to live in a mere hovel in the woods. (...) Money is his idol, and to procure it he gladly foregoes every self-gratification.” In God We Trust, as modern banknotes read.

Speculation

New settlers needed land—but some “interested men” controlled access to land. America was an open country only to a certain extent—as land speculation was spreading West like wildfire, an incredible financial bubble was created. In 1793, America was already a gambler’s paradise. “It is notorious fact,” Weld says, “that(...) land jobbing has led to a series of the most nefarious practices. (...) By the machination of a few interested individuals, who have contrived by various methods to get immense tracts of waste land into their possession, fictitious demands have been created in the market for land, the price of which has consequently been enhanced much beyond its intrinsic worth.” He concludes: “Speculation and land-jobbing carried to such a pitch cannot but be deemed great evils in the community.” It also partly explains why the treaties with Native Americans were broken the one after the other—the thirst for money was always stronger. Isaac Weld also chronicles the terrible downfall of Native Americans, linking it to their taste for alcohol. “The Indians prefer whisky and rum to all other spirituous liquors; but they do not seem eager to obtain these liquors so much for the pleasure of gratifying their palates as for the sake of intoxication.” Once hooked, they “will use every means to gain more; and to do so they at once become mean, servile, deceitful, and depraved, in every sense of the word. Before their acquaintance with (liquors), they were distinguished beyond all other nations for their temperance in eating and drinking.” But that was before the Europeans came—but wait a minute before you carve Natives’ faces in Mount Rushmore! Weld writes: “You could not possible affront an Indian more readily, than by telling him that you think he bears some resemblance to a negro; or that he has negro blood in his veins: they look upon them as animals inferior to the human species, and will kill them with as much unconcern as a dog or a cat.”

(White) Men (only) were created equal.

Isaac Weld went to meet General Washington—and the view of his house in Mount Vernon was tarnished by the unexpected spectacle offered by the slaves’ cabins. “Happy would it have been,” Weld states, “if the man who stood forth the champion of a nation contending for its freedom, and whose declaration to the world was “That all men were created equal, and that they were endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights amongst the first of which were life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness;” happy would it have been, if this man could have been the first to wave all interested views, to liberate his own slaves, and then convince the people (...) it was their duty (...) to give freedom to those whom they had themselves held in bondage.” His remarks are interesting because he hardly ever blames unilaterally. He always tries to understand, even what he dislikes—as a matter of fact contradictions are at the root of every human enterprise. Weld fell in love with the landscapes, and some descriptions are simply breathtaking. But a country is not about landscapes only. Weld went back to Ireland and, as promised, never returned.

The seeds of today’s discontent in America were already sowed in 1793. Of course, this is just one man’s perspective—although backed by some relations from the same period, as Chastellux’, it is to be read with caution. It is interesting but let’s bear in mind that many of the ‘evils evoked by Weld are not typically American. He was looking for a terrestrial Paradise—but this was lost long ago. Wherever you’ll find Man, you’ll find a mixture of good and bad. Men will be men—and they are no better, I’m afraid, in America.

T. Ehrengardt

![<b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 11:</b> Darwin and Wallace. On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties..., [in:] <i>Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnean Society,</i> Vol. III, No. 9., 1858, Darwin announces the theory of natural selection. £100,000 to £150,000. <b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 11:</b> Darwin and Wallace. On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties..., [in:] <i>Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnean Society,</i> Vol. III, No. 9., 1858, Darwin announces the theory of natural selection. £100,000 to £150,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/00d5fd41-2542-4a80-b119-4886d4b9925f.png)

![<b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633. <b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/8caddaea-4c1f-47a7-9455-62f53af36e3f.jpg)