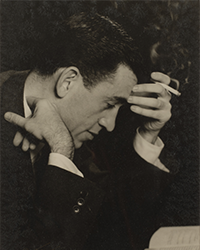

In March of 1850, a father and daughter took their places in front of the camera of J. T. (Jacques) Zealy of South Carolina. This story is not as heartwarming as that introduction sounds. They were not dressed in their Sunday best for this daguerreotype photo shoot. They were not dressed at all. Renty and Delia were slaves. They were there to help a white man “prove” his theory that Africans were an inferior race. They had no choice but to participate in their degradation.

While Zealy was the photographer, he was working at the behest of one of the most noted scientists of the day, Swiss-born Louis Agassiz. In his early years he studied fish, that is, he was an ichthyologist. He developed the most thorough classification of them yet as he identified not only living species but ancient ones through fossils. He then went on to focus on glaciers, concluding that certain rock placements were formed through the movements of glaciers. He correctly concluded that the earth not that long ago had been subject to an ice age.

Agassiz came to America in 1846 and stayed. By 1847, he was a professor at Harvard, and became one the country's most highly respected scientists. If only it ended there.

Agassiz first saw black people after arriving in America. He was disgusted by their appearance, their physical features. He quickly became a proponent of biblical polygenism. Preceding Darwin, it was a form of creationism, teaching that man was created by God as described in the Bible. However, that dealt with white men. Black people were created separately. Agassiz saw it all from a racist perspective. Whites must be a separate, superior race. That was just how God made it, and he stuck to those views even as other scientists changed theirs post-Darwin. He could not accept black people being of the same species as or equal to whites (or to himself). He was not a supporter of slavery per se, but his theory was used to justify that peculiarly awful institution. It would be nice if there was a way around it, but there isn't. Agassiz was a racist.

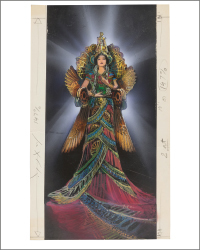

In 1850, Agassiz traveled to South Carolina to visit plantations and observe slaves. At his pseudoscientific best, Agassiz selected some slaves whose appearance he thought would show the inferiority of the African race, at least in accordance with the white perspective. Showing his complete lack of respect for the humans involved, he demanded that his subjects strip for the photographs, Delia included. Both straight on and profile pictures from the waist up were taken of this father and daughter, along with several other slaves. He had the photos sent back to Harvard where he could use them to “prove” white superiority.

The photographs would in time be forgotten, lying in a storage cabinet in the attic of Harvard's Peabody Museum for a century until rediscovered in 1976. Meanwhile, Tamara Lanier of Connecticut was researching her family, based on oral histories handed down by her mother. That history included a man called “Papa Renty,” an African-born South Carolina slave who would be her great-great-great-great grandfather. At some point, she became aware of the photographs at Harvard.

The daguerreotype says that Renty was born in the Congo. An 1834 list of the slaves of B. F. Taylor of Columbia, South Carolina, includes a Big Renty and Renty. Renty and Delia were slaves on the plantation of B. F. Taylor and slaves were typically given the last name of their owner in those days. Ms. Lanier's deceased mother had long told her daughter that their family name was Taylor. Ms. Lanier is confident that she is looking at her ancestors. There is one more thing she now seeks. She wants to bring her family home. She believes she and her family have a right to the likenesses of her ancestors. Harvard does not. About a year ago, Ms. Lanier sued.

She is asking the court to compel Harvard to turn the photographs over to her, as Renty and Delia's descendants and heirs. There are two issues to be decided. The first is whether Ms. Lanier is actually Renty and Delia's heirs. She has much in the way of family history on her side, mostly from her mother, including Renty's name and the family name of Taylor. This is primarily oral history, expressed publicly many years ago, but, unfortunately, the families of slaves don't have the types of family documentation that were created for free people. Personal documents weren't created for property, and that is all slaves were considered to be in Renty's time.

Harvard has denied that Ms. Lanier is Renty's descendant, which clearly and understandably incenses her, as oral tradition is all slaves could pass on. We aren't in a position to evaluate this claim, but the issue of concern for this website is the second one, ownership of paper, in this case, photographs. Assuming Ms. Lanier is the slaves' descendant, does she have the right to possess their photographs? Or, to put it another way, regardless of who their descendants may be, does Harvard have the right to own the photographs under these circumstances?

Normally, a photograph belongs to the person who takes it. These photographs were taken by Zealy, who was paid for them by Agassiz. From Louis Agassiz, they went to his son after his death, who then gave them to Harvard. This is not the first time the subject of a photograph, or those claiming thereunder, have contested rights to a photograph. That is usually a hard case for someone outside of the photographer's chain to win, particularly if the picture was taken in a public place. However, this case is unusual in that Renty and Delia were forced to pose for the camera. They would have had no right to dissent, were unlikely compensated, and even if they were, had no right to enter into a contract since they were slaves. Ms. Lanier's contention is that their images were effectively stolen from them, and through a practice soon outlawed by the 13th Amendment. As such, they should be returned to Renty and Delia's legal descendants/heirs.

This is not an easy case to decide from a purely legal standpoint. Certainly, you could not force someone to pose naked for a photograph today and keep the picture. But, slavery, involuntary servitude, was legal in South Carolina in 1850. There is no doubt how this case would have been decided in 1850, but does that mean it should be so decided today? Agassiz, and his claimant, Harvard, would certainly not have a right to such a photo taken today. If they don't have a right to it, then who better than Renty and his descendants?

The moral argument here is much clearer. Harvard is not standing on the high ground. One wonders why they are contesting this case, or at least not looking for a way out. Their history with this is abominable. They supported Agassiz in his racist work, honoring him for years (and still do) while showing little sympathy for the humiliated slaves he exploited. After the photographs' rediscovery in 1976, Harvard made them available for license, using them as a source of profit. Even their own students formed a group, Harvard Coalition to Free Renty, to get the university to turn over the photographs. Ms. Lanier says in her lawsuit, “Slavery was abolished 156 years ago, but Renty and Delia remain enslaved in Cambridge, Massachusetts.” You would think Harvard would want to extricate itself from this embarrassing situation, even more so now that racism finally has been forced to the forefront of public conversation.

I don't know whether Ms. Lanier is the rightful owner, or her home is the right place for these photographs to go. It is not clear that she has the facilities to properly care for what are monumentally important photographs. These are among, if not the first known photographs of American slaves. A logical landing place for them would be the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, though I don't know if this would be fair to Ms. Lanier or if there is a legal basis. Perhaps the museum could be appointed caretaker for slaves' rights. It would be nice if everyone agreed to this compromise.

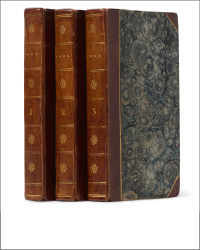

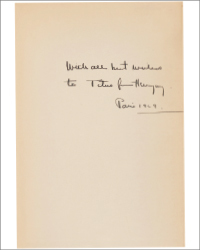

![<b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 16:</b> [Austen, Jane]. A handsome first edition of <i>Sense and Sensibility,</i> the author's first novel. $60,000 to $80,000. <b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 16:</b> [Austen, Jane]. A handsome first edition of <i>Sense and Sensibility,</i> the author's first novel. $60,000 to $80,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/9a74d9ff-42dd-46a1-8bb2-b636c4cec796.png)

![<b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633. <b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/8caddaea-4c1f-47a7-9455-62f53af36e3f.jpg)