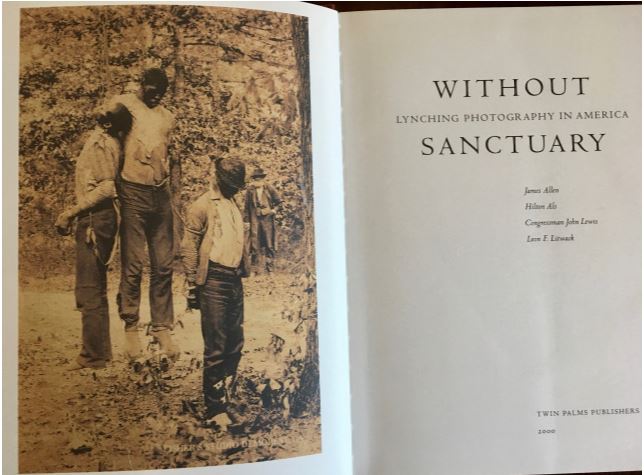

Without Sanctuary; Lynching Photography in America (Twin Palms Publishers) by James Allen is a dark book; so dark you will never forget the first time you opened it nor the terrible 98 pictures it contains. According to the Bible, a tree shall be known by its fruits; what can we say, then, about the ‘poplar trees’ from the ‘gallant South’ that bore 4,000 ‘strange fruits’ (black bodies) between 1877 and 1950? They were lynched by white mobs during barbaric ceremonials that bordered on collective madness. Photographs of the mutilated bodies were taken and used as... postcards! Yes, you read it right. These images are sickening—but the contemptuous smiles of the white folks in the mobs are actually unbearable. So racism in America has a specific story, which is part of a larger history of violence, as lynchings were never reserved to black people. It was a sort of... tradition.

Notwithstanding the opportunistic claims of some European Black organizations, George Floyd’s story is specifically an American drama—this book makes it clear. In certain parts of the country, black lives have never mattered much. Most Southern States did not accept the outcome of the Civil War (1861-65); they resented defeat as a humiliation and their former slaves became a threat to their privileges. Lynching was used as a terror tool, and some 4,000 Black people were lynched between 1877 and 1950 in Alabama, Florida, Tennessee, Louisiana, Arkansas or Mississippi. “For the last 20 years,” Benjamin Schwarz writes (The Killing Fields—Los Angeles Times, 2000), “historians and sociologists have offered various explanations for the ferocity that took hold of the region, elucidating and debating a complex set of factors ranging from changes in crime rates to population movements, to the fluidity and mercurial nature of white and black racial attitudes, to attitudes toward sexuality and gender, to the social relations that grew out of different forms of agriculture.” Horror feeds on horror—soon, lynching wasn’t good enough.

May 15, 1915. Waco, Texas. A Black teen-ager named Jesse Washington confessed to the murder of a White man. A furious mob dragged him outside the courtroom, beating and stabbing him. They tied him with a rope above a fire, bringing him up and down to slowly ton burn him alive. Then people took souvenirs: a bone, the genitals. A kid broke Jesse’s teeth and sold them around—yes, you read it right. Souvenirs also included postcards. James Allen, as an antique dealer, has collected them over the years before compiling them in a book in 2000. In the preface, Member of Congress John Lewis underlines that those murders were characterised by unprecedented sadism and voyeurism; some lynchings lasted up to seven hours! Lynching was like a party, and the grins on those white faces testify that these guys enjoyed every minute of it. On one of those pictures, a skinny white man embraces his girlfriend while pointing at two “strange fruits” hanging in the background—namely Thomas Shipp and Abrama Smith, lynched in Marion, Indiana, in 1930. This particular photograph inspired Abel Meerepol, a white teacher from New York, to write the song Strange Fruit, later sung by Billy Holiday.

June 26, 1919. The front page of the New Orleans State reads: “3,000 WILL BURN NEGRO. The officers have agreed to turn him over to the people of the city at 4’ o’clock this afternoon when it is expected he will be burned. Sheriff and authorities are powerless to prevent it.” Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) is a non-governmental militant association based in Alabama. On its website, we can read: “Extrajudicial mob violence operated hand-in-hand with legal execution as a means of exercising lethal social control over the black population. Neither lynching nor “legal executions” required reliable findings of guilt, and complicit law enforcement officers handed over prisoners to the lynch mob.” According to the same source, these murders were politically motivated: “These lynchings were designed for broad impact—to send a message of domination, to instil fear, and sometimes to drive African Americans from the community altogether.” That’s why these executions were turned into ceremonials, or rather spectacles. And it worked to a great extent, although, as stated by Robert A. Gibson (Yale), “there are records of numerous instances of individual and collective acts of Black retaliatory violence. Although retaliatory violence seemed unreasonable, and often led to more lynching and violence, Blacks frequently armed themselves and fought back in self-defence.”

Reviewing Allen’s book for the Los Angeles Times, Benjamin Schwarz underlines: “Of the victims whose race was known, the vast majority (2,314) were blacks killed by white lynch mobs, but whites also killed 284 whites and black lynchers killed 155 people, all but seven of whom were black.” The Tuskegee Institute confirms that 1,297 White people were lynched between 1882 and 1968—and several ‘strange white fruits’ are to be found in Allen’s book. The postcards phenomenon is also to be put into perspective. “The morbid popularity of lynching postcards actually coincided with a larger postcard craze in the United States between the late 1890s and WWI,” Amy Louise Wood writes in Lynching and Spectacle (The University of North Carolina Press, 2009). “As many newspapers did not have the technology to print high-quality images until the 1920s, postcards also presented for the public a visual record of newsworthy events (...). By 1902, Kodak had issued postcard-size photographic paper on which images could be printed directly from negatives (...) for 10 cents a card.” Nevertheless, all these subtleties must not obscure the openly racist dimension of most lynchings. On a postcard featuring Jesse Washington’s burnt body, one Joe Meyers wrote to a friend of his: “This is the barbecue we had last night.”

In 1980, the US postal service refused to convey offensive images any more. Lynching postcards were now sold under the table. Meanwhile, lynching started to get less fashionable. How come? Did men grow less fierce, and wiser? The EJI has another explanation: “The death penalty in America is a “direct descendant of lynching.” Racial terror lynchings gave way to executions in response to criticism that torturing and killing black people for cheering audiences was undermining America’s image and moral authority on the world stage.” So the death penalty would actually be a progress in the Southern states? A bittersweet fruit, indeed—but what else could have grown on those Southern “poplar trees”?

James Allen’s book is a dark book—and it matters. Just like Las Casas’ La Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias (1552), it reveals the darkest part of the human soul. It is a testimony. And we should all deeply resent it. From my European point of view, those lynchings were not only crimes against Black people but against humanity at large. As the poet once said, and Mr Meerepol later confirmed with his song: “Any man's death diminishes me, because I am involved in Mankind.” Therefore never send to know for whom the rope is tied; it’s tied for thee and me.

Thibault Ehrengardt

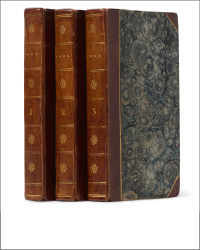

![<b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 16:</b> [Austen, Jane]. A handsome first edition of <i>Sense and Sensibility,</i> the author's first novel. $60,000 to $80,000. <b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 16:</b> [Austen, Jane]. A handsome first edition of <i>Sense and Sensibility,</i> the author's first novel. $60,000 to $80,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/9a74d9ff-42dd-46a1-8bb2-b636c4cec796.png)

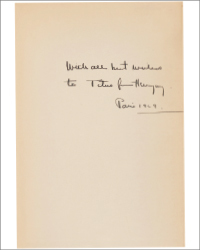

![<b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633. <b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/8caddaea-4c1f-47a7-9455-62f53af36e3f.jpg)