Was this a good deed to help students in particular when they are locked out of their schools in the time of the coronavirus, or a blatant stealing of authors' copyrighted works with no payment in return? It depends on your point of view. According to the Internet Archive, this is a public service. The Authors Guild sees it in a very different light.

The Internet Archive is a nonprofit website that provides free information. Its most notable service, and it is a fantastic one at that, is the Wayback Machine. It lets you look at websites as they appeared on earlier dates. You cannot hide your past from the Wayback Machine. However, they also offer a sort of online library. You can borrow electronic books from the Internet Archive's library, but they aren't the typical ebooks you would take out from your local library, or buy from Amazon. They are more like the electronic books you can read on Google Books. They are scans of pages from a printed book, rather than a true electronic book. You see a picture of the page from the printed book, rather than pages created digitally.

As such, the Internet Archive is not purchasing their ebooks from the publisher, and paying fees or royalties to them, at least some of which, presumable, makes its way to the author. They lend the books as they would a printed copy, rather than through a license like an electronic copy. A library simply buys a printed book, or is given a copy by some kind donor, and then loans that copy to others. What the Internet Archive normally does is take a scan of books they have purchased or been given, and loan the scan out as if it was the physical copy. As such, they normally only lend out one scan per book, and cannot lend their electronic copy to another until the last borrower has returned it. Only if they have multiple copies of a book will they lend out more than one copy, that number being equal to the number of physical copies they possess.

What is the Internet Archive's justification for lending these digitized printed books without paying a fee? It is the legal doctrine that allows libraries to lend physical copies, or allows you to lend a book you purchased to a friend, or sell it to someone else when you are done with it. It is called “fair use,” and it is a long-established legal principle. It says once you have purchased a book, you are free to do what you want with it without paying anything more to the copyright holder. This excludes, of course, making copies and selling/giving away those to others. Copying is a copyright violation. Since they are (normally) only lending digital copies equal to the number of hard copies they own, and have a right to loan, the Internet Archive argues that they are, in effect, lending their printed copy and therefore are covered by the “fair use” doctrine.

Not surprisingly, the Authors Guild does not accept this interpretation of the fair use doctrine. They believe that applies only to the printed books, and photocopying a book is still copying, and lending the photocopy instead is theft of an author's work. We will leave it to legal scholars, and perhaps eventually the courts, to decide this one. You may be wondering how Google gets away with this for their Google Books. Google limits their complete scans to older books that are out of copyright protection. For newer ones, they have reached an agreement with publishers and authors and only display a portion of their in-copyright books.

While the authors group was already highly displeased with what the Internet Archive had done, the stuff really hit the fan a few weeks ago when the the Archive did something especially generous for their readers during the time of the coronavirus epidemic. They call it the “National Emergency Library.” They eliminated the requirement that they not lend out more digital copies than they possessed of physical copies. The argument that this is “fair use” as they are lending no more electronic copies than they physically possess just went out the window. It is hard to see this as being more than copying someone's copyrighted work and handing it out to others. That sounds essentially the same as a pirated edition.

The Internet Archive provides some justifications for their behavior. The claims are based on this being the right, ethical thing to do, that it is a temporary measure only for the duration of the crisis, that the impact on authors is de minimus. These sorts of arguments may make the motivations of the Archive more sympathetic, but they don't address the legality of what is being done. They point out that many libraries, as recommended by the Board of the American Library Association, have been closed due to the virus. The Internet Archive is simply stepping in to provide the books library patrons would be borrowing locally in normal times without further compensation to the publishers and authors. They point out that this is particularly important to students, schooling from home, but not having access to the books they need from school or public libraries. The Internet Archive says that most of their books are not recent bestsellers, but rather, are books designed to promote education that were printed between the 1920s (when copyright protection begins) through the early 2000s. They claim 90% of the books are at least ten years old.

Other arguments include their statistics showing that the majority of books borrowed are viewed for less than 30 minutes. They believe this means that most viewers are looking at these books as if they were pulled off a library shelf, checking to see if it has pertinent information, and discovering it either does not, or what they seek is something small. The Archive also points out that this is a temporary, emergency action. They will go back to only loaning the number of copies of a book for which they have a physical copy at the end of June, or later only if the epidemic continues beyond that date. Finally, they point out that authors can opt to have their books removed from the Internet Archive's lending library.

These may be worthy points, but don't address the legality of what they are doing, or perhaps even fully its morality, considering that what they are generously giving away belongs to someone else. You cannot give away someone else's property no matter how worthy the cause or recipient. That is still theft. This is true even if it is older property, or not of particularly high value. Besides which, the Authors Guild notes that many writers are also in low income brackets and cannot afford to have others giving their work away. As to the option to opt out, that is nice, but I don't have to tell you in advance not to steal from me in order to legally prevent you from stealing from me. You must ask my permission to take my property first, not the other way around.

One can argue whether a crisis such as we currently face morally justifies temporarily lifting the monetary rights of authors and publishers. We can legitimately debate whether the “fair use” doctrine enables us legally to make a photocopy of a book and lend that out instead of the physical copy so long as we own a printed copy. What seems harder to argue is that it is legal (even if we believe it is moral) to do what the Internet Archive is doing, lending out more photocopies than they possess of hard copies. As to what if anything the authors will do, that is another question. They could take the matter to court, but courts do not work with haste. By the time they decide, it is likely the coronavirus will have disappeared, or we all will have died from it.

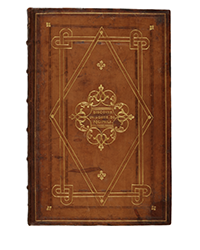

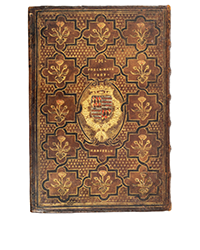

![<b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633. <b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/8caddaea-4c1f-47a7-9455-62f53af36e3f.jpg)

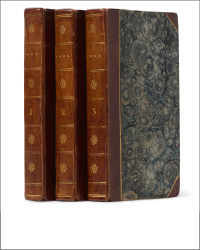

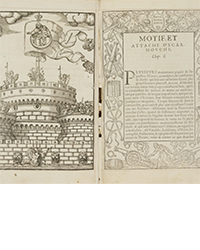

![<b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 16:</b> [Austen, Jane]. A handsome first edition of <i>Sense and Sensibility,</i> the author's first novel. $60,000 to $80,000. <b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 16:</b> [Austen, Jane]. A handsome first edition of <i>Sense and Sensibility,</i> the author's first novel. $60,000 to $80,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/9a74d9ff-42dd-46a1-8bb2-b636c4cec796.png)