Richard Blome’s Description of Jamaica; with the other Isles and Territories in America to Which the English Are Related... (London, 1672) is a book of exception. Although a long time Jamaica specialist, I’ve only held two copies so far, including the National Library of Jamaica’s, in Kingston, Jamaica—two are currently listed on the Internet for around $15,000. This small book was published 12 years after the English captured the island (1655), and it aimed at attracting new settlers to the British colonies in the New World. This political touristic guide captured the fledgling settlements in their prime—with words... and maps!

Although described as an in-8 volume, it’s rather an in-12 (title page, 3 pages, 192 pages, 3 folding maps) published in 1672 by Richard Blome (1635-1705). According to Ashley Baynton-Williams (mapforum.com), Blome was “one of the most interesting, and most active, publishers of illustrated books in post-Restoration London”—but he was no traveller. Thus he relied upon “notes from my honoured friend Sir Thomas Lynch Knight, about the description of the island of Jamaica, whose worth and ingenuity hath lately merited from His Majesty the government of the said isle.” Thomas Lynch knew Jamaica well, indeed. After the untimely sack of Panama by the Jamaican buccaneer Henry Morgan—war with Spain had just ended—, he was sent to replace Governor Thomas Modyford, and to put an end to buccaneering. This was but a political move and the said Modyford was actually involved in the writing of this “small treatise” dedicated to Charles II—this partly explains the special attention paid to Jamaica (64 pages out of 192), but not only. The island then occupied a crucial geopolitical position in the New World, being the stronghold of the dreaded buccaneers; as such, it was at the heart of the negotiations with Spain. With the Treaty of Madrid (1670), not only did the Spaniards officially cede Jamaica to the English, but they also entitled them to trade with their settlements in the New World. Jamaica was becoming a very lucrative trade hub—and it included slave trade, as the Royal African Company was founded in England in 1672. Thus the island was looking for new, and recommendable—meaning no buccaneers—settlers.

Richard Blome gives short but instructive descriptions: climate, vegetation, diseases... At times, his indications are almost like a business plan: “I shall (...) give you an account of the management of a Cocoa Walk,” Blome writes, “with a calculation of its costs, and profits, as it was lately estimated by (...) Sir Thomas Modyford.” 600 acres of land, 6 Negroes (3 men and 3 women), 4 white servants, some material, food for everyone—a £257.5 investment was all one needed to make it in Jamaica in 1672. We learn that a Negro slave cost £20 and a good horse £6—Blome here underlines that horses were plenty on the island, and thus quite cheap. In a word, up to natural resources, everything in Jamaica seemed to concur to the wealth of the newcomer—be he white and not poor, that is; else, this little paradise was a tropical hell.

Blome’s descriptions of the other colonies such as Barbadoes (sic), Maryland, Carolina, Virginia, New England, etc., are also very interesting, and quite amazing. The time lag makes it almost unreal at times. New York, for instance, has only one considerable town called New Amsterdam, located “in a small isle called Mahatan (sic).” It is “large, containing about five hundred well-built houses.” The “country is also possessed with sundry sorts” of Natives amongst whom “fornication is permitted,” and who “worship the Devil whom they greatly fear.” Three pages only are dedicated to what has become one of the most important cities in the world.

The English Short Title Catalogue (British Library) lists three editions of our book for 1672: one “sold by Robert Clavel,” a next one “by J. Williams”, and the last one “by the booksellers of London, and Westminster.” This is the same edition with different title pages; and it actually came in 1673. “An advertisement in March 1673,” Ashley Banton-Williams writes, “announced that it would not be available until Easter of that year.” It was reprinted in 1678 together with The Present State of Algiers by Dorman Newman (the edition of the National Library of Jamaica) and in 1687; the latter under the title The Present State Of His Majesties Isles And Territories In America, “with the text greatly expanded, and adding a set of maps acquired from Morden, previously used in the First Edition of the latter's Geography Rectified (London, 1680),” Banton-Williams underlines. It was translated into French in 1688 as L’Amérique Angloise... (Amsterdam), with seven maps—4 signed Morden, and 3 carefully copied from the originals.

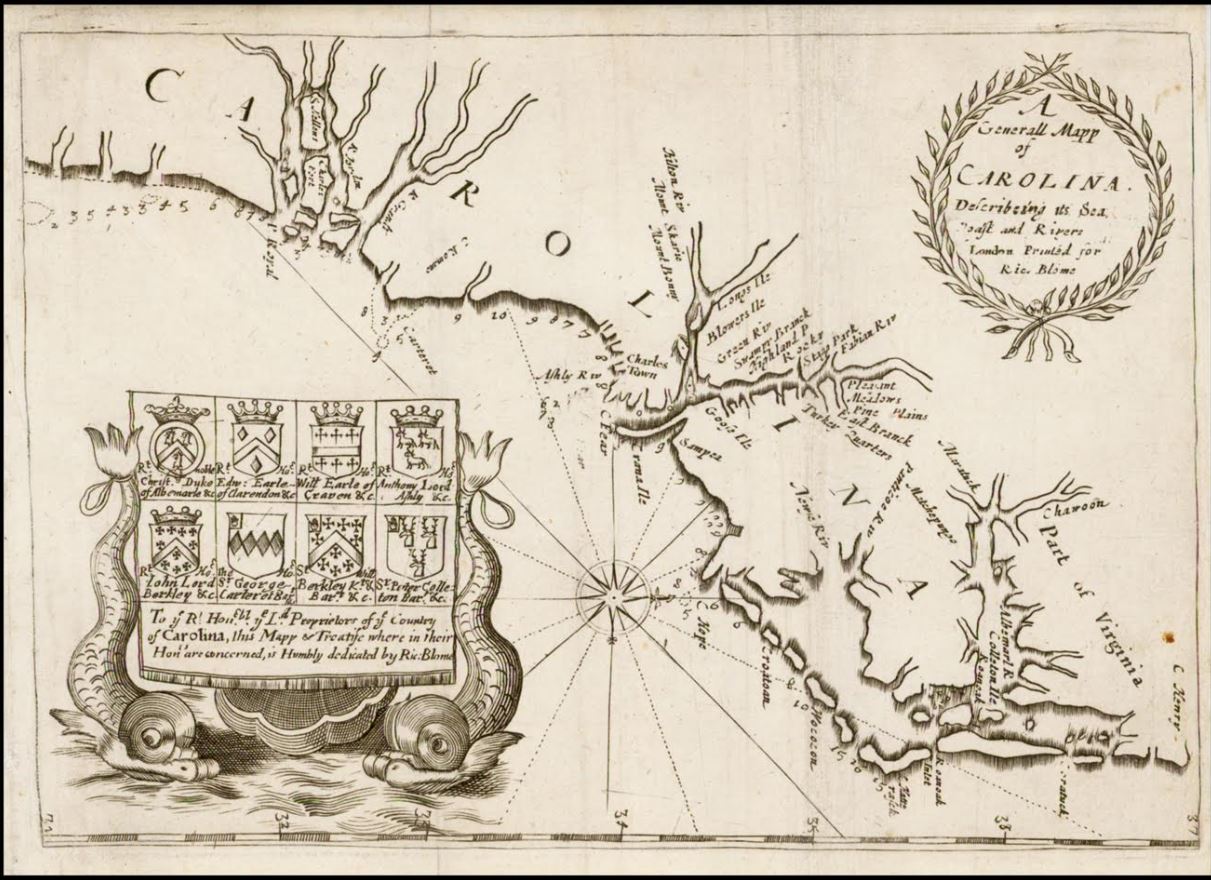

No matter how exciting the reading, the true value if this book lies in its three folding maps. “A new & exact mapp of y. isle of Jamaica” was engraved by Hollar after the map Novassima & Accuratissima Jamaicae Descriptio by John Ogilby (1671), “the prototype of most of the early maps of the island.” (National Library of Jamaica). According to the Royal Collection Trust, it was printed separately by Blome as soon as 1671. “A Generall Mapp of Carolina, Describing Its Sea, Coast and Rivers” is, Ashley Banton-Williams says, “the second printed map of the English Colony of Carolina, pre-dated only by the rare Robert Horne map of 1666.” As far as “Draught of the Sea Coast and Rivers, of Virginia, Maryland, and New England” is concerned, it is “the first English map to illustrate the middle and north-eastern colonies.” In The Mapping of North America (1996), Philip D. Burden explains: “This map is important as it illustrates the region just prior to the great expansion of cartographic knowledge which would commence with the Augustine Herman VIRGINIA AND MARYLAND map of 1673[74] and the John Seller map of New England in 1676.”

Blome’s work wasn’t that appreciated at the time. “Unfortunately, judgements passed by (...) early commentators on one of Blome's principal publications, the Britannia... (Atlas) have oft been repeated as summaries of Blome's career,” Banton-Williams deplores. Bishop W. Nicholson was the most virulent of all, calling it “a most notorious piece of theft out of Camden and Speed—two other cartographers.”

No matter what Bishop Nicholson said 300 years ago—today, these maps determine the value of this book. As a matter of fact, a copy was listed on eBay.com a few weeks ago: nicely bound in contemporary—or 18th century—full leather binding, good to very good condition. And this $15,000 book sold for a few hundred bucks—oh yeah, I forgot to mention: the three maps were missing.

Thibault Ehrengardt

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> ROALD AMUNDSEN: «Sydpolen» [ The South Pole] 1912. First edition in jackets and publisher's slip case. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> ROALD AMUNDSEN: «Sydpolen» [ The South Pole] 1912. First edition in jackets and publisher's slip case.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/0a99416d-9c0f-4fa3-afdd-7532ca8a2b2c.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> AMUNDSEN & NANSEN: «Fram over Polhavet» [Farthest North] 1897. AMUNDSEN's COPY! <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> AMUNDSEN & NANSEN: «Fram over Polhavet» [Farthest North] 1897. AMUNDSEN's COPY!](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/a077b4a5-0477-4c47-9847-0158cf045843.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> ERNEST SHACKLETON [ed.]: «Aurora Australis» 1908. First edition. The NORWAY COPY. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> ERNEST SHACKLETON [ed.]: «Aurora Australis» 1908. First edition. The NORWAY COPY.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/6363a735-e622-4d0a-852e-07cef58eccbe.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> SHACKLETON, BERNACCHI, CHERRY-GARRARD [ed.]: «The South Polar Times» I-III, 1902-1911. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> SHACKLETON, BERNACCHI, CHERRY-GARRARD [ed.]: «The South Polar Times» I-III, 1902-1911.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/3ee16d5b-a2ec-4c03-aeb6-aa3fcfec3a5e.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> [WILLEM BARENTSZ & HENRY HUDSON] - SAEGHMAN: «Verhael van de vier eerste schip-vaerden […]», 1663. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> [WILLEM BARENTSZ & HENRY HUDSON] - SAEGHMAN: «Verhael van de vier eerste schip-vaerden […]», 1663.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/d5f50485-7faa-423f-af0c-803b964dd2ba.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> TERRA NOVA EXPEDITION | LIEUTENANT HENRY ROBERTSON BOWERS: «At the South Pole.», Gelatin Silver Print. [10¾ x 15in. (27.2 x 38.1cm.) ]. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> TERRA NOVA EXPEDITION | LIEUTENANT HENRY ROBERTSON BOWERS: «At the South Pole.», Gelatin Silver Print. [10¾ x 15in. (27.2 x 38.1cm.) ].](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/fb024365-7d7a-4510-9859-9d26b5c266cf.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> PAUL GAIMARD: «Voyage de la Commision scientific du Nord, en Scandinavie, […]», c. 1842-46. ONLY HAND COLOURED COPY KNOWN WITH TWO ORIGINAL PAINTINGS BY BIARD. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> PAUL GAIMARD: «Voyage de la Commision scientific du Nord, en Scandinavie, […]», c. 1842-46. ONLY HAND COLOURED COPY KNOWN WITH TWO ORIGINAL PAINTINGS BY BIARD.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/a7c0eda0-9d8b-43ac-a504-58923308d5a4.jpg)

![<b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 11:</b> Darwin and Wallace. On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties..., [in:] <i>Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnean Society,</i> Vol. III, No. 9., 1858, Darwin announces the theory of natural selection. £100,000 to £150,000. <b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 11:</b> Darwin and Wallace. On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties..., [in:] <i>Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnean Society,</i> Vol. III, No. 9., 1858, Darwin announces the theory of natural selection. £100,000 to £150,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/00d5fd41-2542-4a80-b119-4886d4b9925f.png)