The world of books, maps, manuscripts and ephemera seems to have always lived within its own reality. Decades ago rare and unusual examples were often obscure and required experts to first find, explain and then place material in important library and private collections. It was business but often a scholarly field populated by celebrated luminaries on both sides of the transaction. Taken together the field, steeped in history, was also soaked in prestige. The heyday was arguably the later decades of the 19th century. Families were creating fortunes but often lacked social recognition to match their economic standing. Many became the great collectors of their age and in some cases, among the greatest collectors of all time.

Today success is measured in many more ways. The wealthy tend to be better educated and to sometimes achieve financial success that dwarfs their ability to spend it. Some choose printed material as a collecting focus but it is simply one option among many. Some buy airplanes or boats. Paintings seem to be very important, both for their visibility and emotional appeal. Across all categories, It’s widely said that the best sells best, suggesting that the finest examples find new homes while lesser copies struggle to some extent. In the works on paper category particularly this is widely reported.

Availability and pricing, be what they may, we are entering a new phase, the era of the highly-focused collector/collection and this will further transform how material is understood and marketed.

Books, as well as manuscripts, maps and ephemera are desirable but it is increasingly possible to contextualize and “place” material in contexts that will further define appropriateness for collecting generally and some collections specifically. Whether offered at auction, by a dealer or marketed directly by a collector there will be two distinctly different valuations; the general valuation and the value of an item to a specific collector/collection.

Some dealers work hard to contextualize their material, a process that often begins with the question; is this important and if so why? They then go onto telling its story. They do not necessarily charge more but they are more likely to make sales because, context, for the acquirer, is very valuable.

Most dealers though rely on would-be buyers to know it’s of interest to them. Sellers simply pick up the bibliographic details that make the “finding” easy. And if a scholarly dealer has explained the significance they’ll often crib the details without ever really knowing the story. In this difference is the very essence of what separates the best rare book sellers from used book sellers: knowing the material.

In this transition, many more sellers will need to become scholarly in their approach. Auction houses have been adjusting to this rising bar for decades and this is part of the reason that their sales have strengthened. The emerging next generation of collectors will have more knowledge and acquire more narrowly. For the dealer then the challenge will be to explain their material in fresh incisive ways.

The RBH Transaction Database will help. Now in its fifteenth year this database includes more than eight million records that span auction and, to a lesser extent, dealer activity over the period 1860 to yesterday. Relative pricing is interesting and probability of reappearance now essential facts that the would-be serious seller needs to be mindful of. As to why? It’s because buyers increasingly know some of the story and expect dealers to complete it.

For that, we are an extraordinary resource. It’s where the best dealers have long been and it’s where the next generation of scholar-booksellers, collectors and institutions are today.

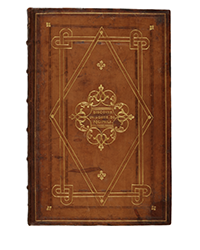

![<b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633. <b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/8caddaea-4c1f-47a7-9455-62f53af36e3f.jpg)

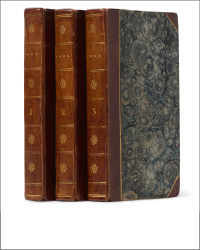

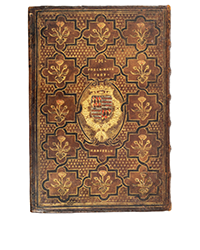

![<b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 16:</b> [Austen, Jane]. A handsome first edition of <i>Sense and Sensibility,</i> the author's first novel. $60,000 to $80,000. <b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 16:</b> [Austen, Jane]. A handsome first edition of <i>Sense and Sensibility,</i> the author's first novel. $60,000 to $80,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/9a74d9ff-42dd-46a1-8bb2-b636c4cec796.png)