Matthews and friends

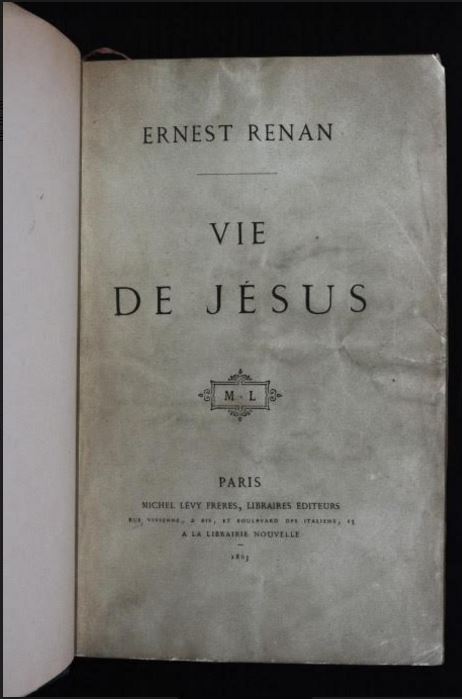

For many, Renan’s book was a renegade’s work—at the time, Jean Guéhenno wrote that it was “the chronicle of God’s agony within one of the most religious, yet clear-sighted, souls ever.” Indeed, Renan had lost his faith. “To write the history of a religion,” he states in his preface, “it is necessary, firstly, to have believed it (otherwise we should not be able to understand how it has charmed and satisfied the human conscience); in the second place to believe it no longer in an absolute manner for absolute faith is incompatible with sincere history.” Renan had a “modern” approach. His book was the first chapter in a series entitled The History of the Origins of Christianity1. In the second volume, The Apostles (Paris, 1866), he explains: “To shake the faith of someone is what I really do not intend to do. This kind of works must be executed with supreme indifference, just as if one was writing for an uninhabited planet.” A learnt man, he gives a precious and reasonable overview of the four Gospels: Matthew deserves our full trust as far as the discourses of Jesus are concerned; Luc was less an evangelist than a biographer; Marc’s Gospel is the firmest, the more precise—compiled from to the memories of an eyewitness, probably Peter himself; and John’s Gospel continuously displays the ulterior motives of a sect willing to convince, and though featuring “admirable gleams, some traits which truly come from Jesus,” is more into metaphysics and dark dogmas. But what really makes his book different is that Renan had travelled to the holy land—with his sister, in 1861. That’s where he wrote his book, as a matter of fact, contemplating the countries he was talking about. It gave him a carnal approach to the Bible. His description of Galilee is haunted by the luminous spectre of Jesus, who once walked this ground. “The first task of the historian,” he says, “is to sketch well the environment in which the events he recounts took place.” His geographical approach of history (inherited from the German school) is limpid in this book—and indeed, it seems like Renan had “secular”, or “historical” visions while he was there. As a matter of fact, not only was his biography of Jesus historical, but it was also very emotional.

A Few Historical Facts

The infallibility of the Scriptures was way behind Renan: “That the Gospels are in part legendary is evident,” he writes, “since they are full of miracles and of the supernatural.” He goes on: “Jesus was born at Nazareth, and it is only by a rather embarrassed and round-about way that, in legends respecting him, he is made to be born at Bethlehem.” Renan also calls a myth the famous Massacre of the Innocents, supposedly ordered by Herod the Great to get rid of Jesus.

Jesus, Renan says, was a simple man, and “although born at a time when the principle of positive science was already proclaimed, he lived entirely in the supernatural.” In fact, under his pen, Jesus appears like stranger to the low occupations of the Pharisees of Jerusalem. He wasn’t into analysing the Law (Torah), but he believed “that by praying he could change the path of clouds, arrest disease, and even death.” He had, Renan adds, an exaggerated belief in the power of man, and profound idea of the familiar relations of man with God—“beautiful errors, which were the secrets of his power.”

The Gospels portray Jesus as a “reformer”, constantly challenging the religious Law. He was clearly a man of rare understanding, but he was no intellectual. Jesus was a man of action, and a man of joy. His relationship with “the austere” John the Baptist also appears with an unprecedented clarity. When they met on the bank of the Jordan, Jesus became “during some weeks at least, the imitator of John.” The influence of the Baptist on Jesus was more hurtful than useful, Renan says, as “it checked his development; for everything leads us to believe that he had, when he descended towards the Jordan, ideas superior to those of John, and that it was by a sort of concession that he inclined for a time towards baptism. Perhaps, if the Baptist (...) had remained free, Jesus would not have been able to throw off the yoke of external rites and ceremonies, and would then have remained an unknown Jewish sectary.” But he soon developed what Renan calls the “transcendent disdain” that placed him above all things. My kingdom is not of this world, as he said—probably, argues Renan, his most genius statement.

Renan also revisits the foundation myth of the resurrection of Lazarus—“perhaps the ardent desire of silencing those who violently denied the divine mission of Jesus, carried his enthusiastic friends beyond all bounds. It may be that Lazarus, still pallid with disease, caused himself to be wrapped in bandages as if dead, and shut up in the tomb of his family.” When Jesus arrived, surrounded by an important crowd, Lazarus suddenly walked out of the tomb, and people shouted “Miracle!” Yes, this founding myth might come from Lazarus’ “ardent desire” to support his friend—who would deny the key role human emotions have played in the history of humanity?

The Style and the Historian

“The style is the man himself,” Buffon once said—and he said it all. Renan wrote in such a tender and melancholic style! Some passages of his book are like Christian lullabies, and you will feel like being rocked in the bosom of Jesus Christ at times. His incredible power of evocation makes his book fascinating. Perrine Simon-Nahum says: “The argument that proved the most harmful to Renan was, curiously, the only positive point upon which both his enemies and supporters agreed: his style, the poetry of his evocation, his fluid and charming writing.” Jesus suddenly ‘appears’ to us—appetizer, any one?—as a man of exception, full of tenderness and joy, surrounded by a small “family” of enthusiastic young disciples and devoted women; as the end draws nearer, the burden of his destiny falls on his shoulder, he becomes a grave, almost dark figure—we are entering into the intimacy of Christ, and this is quite exciting. “Renan saved the Gospel from dust; laziness, indifference and ignorant bigotry had overwhelmed it and it was suffocating,” wrote J. Orth (Simon-Nahum). This compliment was coming from one of Renan’s worst opponents—indeed, the more he was praised as a popularizing author, the less convincing he appeared as a historian.

At the end of the day, Ernest Renan was rehabilitated, elected to the Académie Française, and even appointed administrator of the same Collège de France. “But make no mistake!’ warns Simon-Nahum. “As soon as dead, he sank into oblivion—mostly because of his ‘Vie de Jésus’.” Indeed, his peers never understood his project—or did they understand it too well, on the contrary? Though he “succeeded in assuaging one of the great anxieties of his time, the antagonism between science and religion,” according to Encyclopedia Britannica, he probably gave too much room to feelings. And History had another agenda. “In the 1880s,” Simon-Nahum concludes, “History was placed under the sign of the historical method—not of feelings.” The French historians would rather focus on facts, not on style—the letter that kills, rather than the Spirit that gives life. The Pharisees had won again. Poor Buffon! Poor Jesus! Poor us!

(c) Thibault Ehrengardt

1 It is composed of the following titles: Vie de Jésus (1863)/Les Apôtres (1866)/Saint Paul (1869)/L’Antéchrist (1873)/Les Evangiles et la seconde génération chrétienne (1878)/L’Eglise chrétienne (1879)/Marc Aurèle (1883)/Index général (1883).

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> ROALD AMUNDSEN: «Sydpolen» [ The South Pole] 1912. First edition in jackets and publisher's slip case. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> ROALD AMUNDSEN: «Sydpolen» [ The South Pole] 1912. First edition in jackets and publisher's slip case.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/0a99416d-9c0f-4fa3-afdd-7532ca8a2b2c.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> AMUNDSEN & NANSEN: «Fram over Polhavet» [Farthest North] 1897. AMUNDSEN's COPY! <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> AMUNDSEN & NANSEN: «Fram over Polhavet» [Farthest North] 1897. AMUNDSEN's COPY!](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/a077b4a5-0477-4c47-9847-0158cf045843.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> ERNEST SHACKLETON [ed.]: «Aurora Australis» 1908. First edition. The NORWAY COPY. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> ERNEST SHACKLETON [ed.]: «Aurora Australis» 1908. First edition. The NORWAY COPY.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/6363a735-e622-4d0a-852e-07cef58eccbe.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> SHACKLETON, BERNACCHI, CHERRY-GARRARD [ed.]: «The South Polar Times» I-III, 1902-1911. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> SHACKLETON, BERNACCHI, CHERRY-GARRARD [ed.]: «The South Polar Times» I-III, 1902-1911.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/3ee16d5b-a2ec-4c03-aeb6-aa3fcfec3a5e.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> [WILLEM BARENTSZ & HENRY HUDSON] - SAEGHMAN: «Verhael van de vier eerste schip-vaerden […]», 1663. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> [WILLEM BARENTSZ & HENRY HUDSON] - SAEGHMAN: «Verhael van de vier eerste schip-vaerden […]», 1663.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/d5f50485-7faa-423f-af0c-803b964dd2ba.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> TERRA NOVA EXPEDITION | LIEUTENANT HENRY ROBERTSON BOWERS: «At the South Pole.», Gelatin Silver Print. [10¾ x 15in. (27.2 x 38.1cm.) ]. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> TERRA NOVA EXPEDITION | LIEUTENANT HENRY ROBERTSON BOWERS: «At the South Pole.», Gelatin Silver Print. [10¾ x 15in. (27.2 x 38.1cm.) ].](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/fb024365-7d7a-4510-9859-9d26b5c266cf.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> PAUL GAIMARD: «Voyage de la Commision scientific du Nord, en Scandinavie, […]», c. 1842-46. ONLY HAND COLOURED COPY KNOWN WITH TWO ORIGINAL PAINTINGS BY BIARD. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> PAUL GAIMARD: «Voyage de la Commision scientific du Nord, en Scandinavie, […]», c. 1842-46. ONLY HAND COLOURED COPY KNOWN WITH TWO ORIGINAL PAINTINGS BY BIARD.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/a7c0eda0-9d8b-43ac-a504-58923308d5a4.jpg)

![<b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 11:</b> Darwin and Wallace. On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties..., [in:] <i>Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnean Society,</i> Vol. III, No. 9., 1858, Darwin announces the theory of natural selection. £100,000 to £150,000. <b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 11:</b> Darwin and Wallace. On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties..., [in:] <i>Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnean Society,</i> Vol. III, No. 9., 1858, Darwin announces the theory of natural selection. £100,000 to £150,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/00d5fd41-2542-4a80-b119-4886d4b9925f.png)