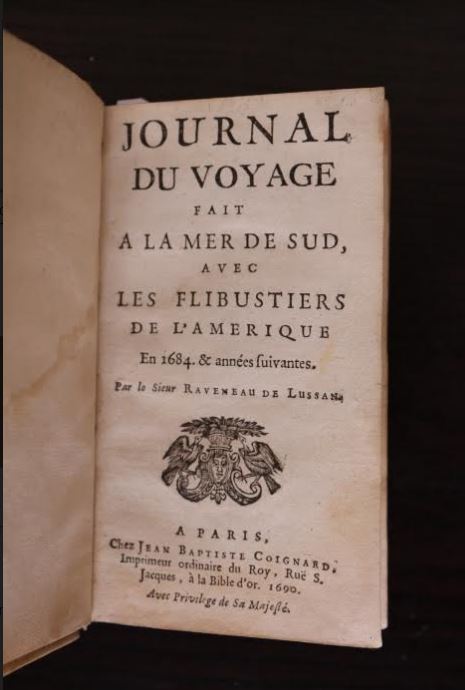

Twenty severed heads, on a buccaneer's bark, yo-oh-oh! Welcome to the merciless world of the buccaneers* (or flibustiers), those terrible people who swarmed the Spanish Americas in the second half of the 17th century. Raveneau de Lussan's Journal du Voyage Fait à la Mer de Sud avec les Flibustiers de l'Amérique en 1684... (Coignard, 1689) is arguably the best account of its kind after Esquemeling's. Smells of blood, sweat and tears arise from the pages of the first edition published a few months after the events. Get on board, mate – but be prepared! It ain't no fairy tale.

Let's make it clear, Esquemeling's Bucaniers of America (Jan ten Hoorn, 1678, for the very first edition in Dutch/Crook, 1684, for the first English edition), which describes the “exploits” of the first generation of those bold West-Indian warriors, is the best book about buccaneering ever. The buccaneers were the terror of the Spaniards in America, who feared them beyond reason. Their reputation crossed the ocean, and attracted legions of villains from all over the Old World. Raveneau de Lussan was, on the contrary, from an “honest family”, and nothing forced him to turn buccaneer: “I couldn't explain my deep inclination,” he confesses, “except that I have always been fond of traveling. (…) With this, I had what I dare not call a martial mind, but let's say the burning desire to partake in some battle or siege. As soon as I heard the beating of the drums in the streets (of Paris), I was carried away with such strength that I'm still transported with joy and excitement at the simple memory of it.” He first joined the army, and then embarked for America in 1679, aged roughly 16. “My parents spared nothing their tenderness for their unruly son dictated them, but they were unable to make me change my mind.” The first 3 years he spent in Saint Domingue (Haiti) left him with so many debts that he decided to borrow some money from the Spaniards. “What's convenient with those particular loans,” he says, “is that no one expects you to repay them.” In 1684, our man joined the famous French buccaneer Laurent de Graff and left Petit Goâve, Saint Domingue (Haiti), on November 22 - “one of the happiest days of my life!”

In March 1685, he walked across the Isthmus of Panama with 263 buccaneers to raid Panama, located on the shore of the South Sea (or Pacific Ocean). The Jamaican buccaneer Henry Morgan had already led a successful expedition across the Isthmus some twenty years earlier. Before that, the Spanish settlements on the West coast of the continent had been spared by the buccaneers, mainly because they were remote and difficult of access. As a result, the Spaniards from this region hardly fortified their rich cities, and were almost unable to sustain a battle. Thus, although they usually outnumbered their assailants by far, they were regularly defeated. They tried to defend themselves, even hiring the skills of mercenaries from various nations to assist them – they were called “the Greeks” - but their main strategy consisted in running away with their riches as soon as they sighted a buccaneer. As Raveneau puts it, “our safety lied as much in our boldness than in their cowardice.”

A modern critic wrote that had this account been less confused, it would have been a very good adventure novel. But it is much more than that! Reading it is like entering a dog-eat-dog world full of villains, gold and blood. Long ago, the “pirates” had their “fun” in the burning sun, indeed. And Raveneau de Lussan's relation is genuine, as testified by the letters of recommendation from the French Governor of Saint Domingue added to his relation. His journal was first published in 1689 by Jean-Baptiste Coignard**, known for putting out quality books. In 2015, Christie's sold a copy of the first edition bound in full morocco and featuring the arms of Louis XIV for more than 16,000 pounds. But this an exceptional price for an exceptional copy. A common, and very nice copy of the first edition, can usually be found between 1,500 and 1,800 euros

The second edition - though the third one of 1693 (Coignard's widow and son) reads “second edition” -, published as soon as 1690 by the same Coignard, is worth a few hundred euros less. It is a small in-12 volume printed on thick paper with small but quite readable fonts − Elsevier style. Upon opening it, the smell of powder rushes your nostrils! Raveneau de Lussan takes you to the very heart of the action. Plundering, torturing to death, murdering, kidnapping or beheading, everything is here exposed (except rape, which was apparently forbidden by common agreement before each expedition, but this particular point is suspicious, isn't it?). Upset by the Spaniards who fired poisoned bullets at them, the buccaneers killed twenty prisoners and then sent their severed heads to the President of Panama on a bark. “A somewhat violent expedient, I must say,” Raveneau confesses, “but the only way to bring the President to a better state of mind.” It is, indeed, always difficult to discuss with an unreasonable man.

The buccaneers saw themselves as legitimate soldiers, since they acted on commissions – as a matter of fact, Raveneau's relation was published by Coignard, “ordinary printer for the King”, with due “privilege of His Majesty”, and dedicated to Secretary of State Marquis de Seignelay. It was obviously no shame to be associated with such a book. The buccaneers were good Catholics, too – they chanted the Te Deum on the bodies of their victims, and the French ones always fought the English ones whenever the latter disrespected Catholic symbols while looting a city. Yet, they led a bizarre kind of war. Crossing back the Isthmus in 1688, Raveneau rages against the mosquitoes that filled the air: “You can feel them rather than see them, and their poisoned darts are like fiery stings (…). Enduring their harassment is an ordeal (…). We grew desperate under their attacks, and they literally drove us out of our senses with rage.” A Spaniard could have said just the same about the buccaneers!

These restless and swarming enemies were elusive, and although in want for everything – they mended the sails of their miserable embarkations with their own shirts –, they were tireless and ever motivated. The caimans, the snakes, the burning sun, hunger or thirst – nothing could discourage them. The Spaniards feared them because, as Raveneau says, “they would risk everything to gain almost nothing”. They were thoughtless people, too; many survived several years of want and war, only to leave the South Sea with empty pockets after they had lost their ill-gotten booty on gambling! When the weary troops decided to go back to the North Sea (or Atlantic Ocean), Raveneau realized that all the money he had thus earned was now a threat to his life: “Those who had lost their share by gambling plotted to murder those among us who had won the most.” He then entrusted a large part of his booty to other buccaneers, who agreed to carry it across the Isthmus providing that they would keep half their charge on arrival. “Quite a high price to pay,” he says. “But what won't we do to keep death away?” He was right to be careful. A buccaneer, especially a broke one, was a wolf to a buccaneer.

The buccaneers usually abode by some rules known as “chasse-parties”, or preliminary agreements, that notably defined the conditions of compensation for the future wounded fighters. After several months spent fighting in the Bay of Panama, “there were fourteen maimed persons, and six badly injured. We gave six hundred pieces of eight to each of the latter, and a thousand to the others, as we had always done. All the money we had so far gained was thus spent on these compensations.” But “brotherhood” had its limits. To go back to the North Sea, the buccaneers walked to the Yara river and descended it on makeshift rafts made of two or three tree trunks tied together with creepers. Some drowned in the rapids, others were ambushed by their own folks: the aforementioned broke buccaneers. “Those villains had sailed before us, and they hid behind some rocks on the bank, knowing that we all had to pass them. (…) They waited for five English men, known to be the richest among us, and slaughtered them, and stripped them of everything. (…) With a friend, we found their bodies lying on the river bank.”

Though they kept on boasting about their skills and their many victories, many buccaneers suffered post traumatic stress. Back to Saint Domingue among their French peers, some were still at war in their heads. “Some of us had been so mentally disturbed and weakened by all the miseries we had endured, that their heads were full of Spaniards; in so much that, seeing riders on the shore from the desk of our boat, they would run to their rifles and fire at them, identifying them with enemies although we told them that they were friends!” At the time, personal feelings weren't as exposed as they are today. But a few words are sometimes more meaningful than a thousand ones; especially when they are the last ones of an account: “As for myself, I had been so convinced that I would never return, that I spent fifteen days thinking I was living an illusion; to such an extent that I refused to sleep, fearing that I might wake up in the middle of the countries I had left.” Adventure novels? Sissy stuff, mate!

(c) Thibault Ehrengardt

* The English term “buccaneer” comes from the French “Boucaniers”, who were cooking meat according to the West Indians tradition of smoking it on a “boucan” - sort of barbecue. They were, at first, illegal colonists, who lived in small groups in the “savannas” (or plains) of St. Domingue, far from all social life. The Spaniards, who were the only legitimate owners of these lands since Columbus had discovered them in the name of the Queen of Spain, decided to chase them away by slaughtering all the savage cows they fed upon. Some of them then jumped on small boats to attack the Spaniards and became the “Flibustiers” - or “free-booters”, a word deriving from Dutch. Very soon, they became dreadful warriors used by the colonies such as St. Domingue or Jamaica (where they kept the name of “buccaneers”) to act as soldiers during conflicts. The Governors issued “commissions”, which gave them permission to attack the enemies of the colony and differentiated them from pirates. In Jamaica, they became so important that their most infamous leader, Henry Morgan, was eventually appointed Governor of the island.

** His beautiful family mansion in Nogent-sur-Marne, in the suburbs of Paris, was once a dull and dark police station. It has recently been rehabilitated and is now a cultural center.

*** In France, Raveneau de Lussan's account was separately published several times: in 1689 and 1690 by Coignard; in 1693 (by Coignard's widow and son); and then by Lefebvre in 1705. Afterwards, it became part of the famous collective edition in 4 volumes about buccaneering (Trevoux, 1744), which also contains Esquemling's Bucaniers of America and A General History of the Pyrates.

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> ROALD AMUNDSEN: «Sydpolen» [ The South Pole] 1912. First edition in jackets and publisher's slip case. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> ROALD AMUNDSEN: «Sydpolen» [ The South Pole] 1912. First edition in jackets and publisher's slip case.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/0a99416d-9c0f-4fa3-afdd-7532ca8a2b2c.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> AMUNDSEN & NANSEN: «Fram over Polhavet» [Farthest North] 1897. AMUNDSEN's COPY! <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> AMUNDSEN & NANSEN: «Fram over Polhavet» [Farthest North] 1897. AMUNDSEN's COPY!](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/a077b4a5-0477-4c47-9847-0158cf045843.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> ERNEST SHACKLETON [ed.]: «Aurora Australis» 1908. First edition. The NORWAY COPY. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> ERNEST SHACKLETON [ed.]: «Aurora Australis» 1908. First edition. The NORWAY COPY.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/6363a735-e622-4d0a-852e-07cef58eccbe.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> SHACKLETON, BERNACCHI, CHERRY-GARRARD [ed.]: «The South Polar Times» I-III, 1902-1911. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> SHACKLETON, BERNACCHI, CHERRY-GARRARD [ed.]: «The South Polar Times» I-III, 1902-1911.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/3ee16d5b-a2ec-4c03-aeb6-aa3fcfec3a5e.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> [WILLEM BARENTSZ & HENRY HUDSON] - SAEGHMAN: «Verhael van de vier eerste schip-vaerden […]», 1663. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> [WILLEM BARENTSZ & HENRY HUDSON] - SAEGHMAN: «Verhael van de vier eerste schip-vaerden […]», 1663.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/d5f50485-7faa-423f-af0c-803b964dd2ba.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> TERRA NOVA EXPEDITION | LIEUTENANT HENRY ROBERTSON BOWERS: «At the South Pole.», Gelatin Silver Print. [10¾ x 15in. (27.2 x 38.1cm.) ]. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> TERRA NOVA EXPEDITION | LIEUTENANT HENRY ROBERTSON BOWERS: «At the South Pole.», Gelatin Silver Print. [10¾ x 15in. (27.2 x 38.1cm.) ].](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/fb024365-7d7a-4510-9859-9d26b5c266cf.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> PAUL GAIMARD: «Voyage de la Commision scientific du Nord, en Scandinavie, […]», c. 1842-46. ONLY HAND COLOURED COPY KNOWN WITH TWO ORIGINAL PAINTINGS BY BIARD. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> PAUL GAIMARD: «Voyage de la Commision scientific du Nord, en Scandinavie, […]», c. 1842-46. ONLY HAND COLOURED COPY KNOWN WITH TWO ORIGINAL PAINTINGS BY BIARD.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/a7c0eda0-9d8b-43ac-a504-58923308d5a4.jpg)

![<b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 11:</b> Darwin and Wallace. On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties..., [in:] <i>Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnean Society,</i> Vol. III, No. 9., 1858, Darwin announces the theory of natural selection. £100,000 to £150,000. <b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 11:</b> Darwin and Wallace. On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties..., [in:] <i>Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnean Society,</i> Vol. III, No. 9., 1858, Darwin announces the theory of natural selection. £100,000 to £150,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/00d5fd41-2542-4a80-b119-4886d4b9925f.png)