The chance to visit New York City this past month reminded me anew that, for book collectors and those who do historical research both the New York Public Library and the New York Historical Society are exceptional resources. My subject for research: Abraham Tomlinson, who during the period 1840 to 1858 was an acquirer of Revolutionary War manuscripts and printings. And the reason for personal interest in his story: he was a once recognized and more recently a mostly forgotten acquirer/collector of material whose history has recently been illuminated by the sale of an inventory book he kept of a collection he hoped to sell to the Astor Library in 1859. The story is complex and hardly underway but already coming together because of the extraordinary records maintained by these important institutions.

I wrote a story in the July issue of RBM about the Tomlinson Collection and since spent a few days in New York City to examine related files. Here is an update and at the end of this brief article a link to my earlier story.

Mr. Tomlinson is long gone but records of his collecting/acquiring exploits live on in fragmentary files and references in libraries, online, and in the printed work he published in 1855: Soldier’s Journals – 1758 + 1775. He’s an acquired taste with a name that is distinctive enough that he becomes reasonably visible when searching the right places.

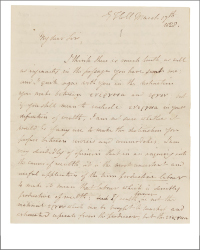

In the RBH Transaction History for Abraham Tomlinson we have 46 records. The most recent is an inventory of Mr. Tomlinson’s Revolutionary War manuscript and artifact collection. I purchased it at Swann’s this year and have since then been trying to understand where his material is today. In that pursuit I am enormously helped by notes that Radford Curdy, the great Dutchess County historian inserted, in the 1950’s or sixties, into the back of Mr. Tomlinson’s manuscript account. Said another way, for about $3,000 I bought a wonderful puzzle.

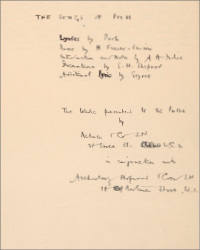

So I then recently went to the New York Public Library. I did not find any of the easily identified Tomlinson items, many, possibly most, which have the following mark:

Tomlinson Collection – Deposited by

Mercantile Library Association

They once did though and we know this as they have a file of seventy-two pages that relate to the Tomlinson Collection and their communications with various parties about it. We know for instance that NYP, which had the material as an uncatalogued deposit from around 1918 to 1946, wanted to buy the collection but could not agree with the Mercantile Library on a price.

These records include letters to and from the Mercantile Library as well as internal memos about the material, its value and New York Public’s offers to buy it. The material was eventually reviewed by Parke-Bernet in the mid 1940s, at the behest of the Mercantile Library, and some of it, 148 items and lots to be specific, eventually consigned to them. We also know that some of the material appeared in a Parke-Bernet sale in 1947 but have not yet connected most of the material to other PB sales. That will become clearer once a careful transcription of the original inventory submitted to the Astor is complete. The handwriting though is a challenge.

As to the Mercantile Library, the collection’s owner from about 1860 to about 1947, they issued periodic lists of holdings but so far I have found no references to Tomlinson manuscripts or to any other manuscripts in them. Perhaps such a publication of manuscripts was issued separately but this is only speculation. For the moment that’s a dead end.

What has emerged is New York Historical Society’s relationship to the Tomlinson collection. In their online collection there are references to holdings that include the Tomlinson/Mercantile mark and an afternoon there proved enormously valuable. They have nineteen items with the Tomlinson mark, all of which I examined and photographed, and as importantly they listed in their records the source and date of purchase. Deep into their 1950 records are two references to Tomlinson purchases from the Carnegie Book Shop for which they paid about $1,400. Voila! Another lead.

The nineteen items are broadsides and documents, a category somewhat ignored by earlier generations and not one highlighted in earlier descriptions of the collection.

I will now try to trace the Carnegie material back to its transfer from the Mercantile Library and cannot yet say if it was at auction, then which auction or auctions, or whether it might have been by private sale.

When available I’ll search the Carnegie catalogues from the period 1945 to 1955 but do not yet know how these items will be described.

In the meantime, we have now identified the nineteen Tomlinson items that have passed through the auction rooms and turned up in RBH records, another nineteen lots held by New York Historical, and roughly 18 that were, in the mid 1930s in the collection of Washington Headquarters in Newburgh, New York. There will certainly be other items in the Carnegie catalogues or offer letters that will further identify material handled by this source.

In conclusion, I know that institutions as a general rule do not indelibly mark collectable material but this effort to reconstruct the Tomlinson collection would be infinitely more difficult, and possibly impossible without such marks so I’m grateful for them.

In the meantime an item with the Tomlinson mark has come up at auction and I’ve bought it. I did so believing there won’t be many. The collection may have a thousand parts but I’m already convinced they are mainly in institutional collections. We’ll see.

Link to article on the Tomlinson Collection.

![<b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633. <b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/8caddaea-4c1f-47a7-9455-62f53af36e3f.jpg)