The prison of la Bastille, which once stood in the middle of Paris, is the ultimate symbol of the French Revolution. When an angry mob captured it on July 14th, 1789, it became a landmark in French history. Many books had been written about la Bastille, the tool of the “tyrannical” Ancien Régime, but when M. Linguet published the relation of his two-year imprisonment in 1783*, he did something none of his illustrious predecessors had done: he gave a physical description of the belly of the beast.

La Bastille was no ordinary prison; it was a “state prison.” A simple “lettre de cachet”—an order coming directly from the King—could send you there ad vitam aeternam, regardless of your position or condition. These letters had a tremendous power. Simon-Nicolas-Henri Linguet (1736-1794), for instance, remained at la Bastille for 20 months between 1781 and 1782, almost losing his life there, and until the day he died on the guillotine in 1794, he never knew why. Well, he had a slight idea—but without any official act of accusation, there was no way he could defend himself. “On which ground had I been sent to prison?” he asks. “Had someone only told me? Will someone ever tell me?” In an article published in 2007, the historian Michel Biard describes M. Linguet as “a founder of journalism in France, who published “Journal de politique et de littérature”, from 1774 to 1776, and then “Annales politiques, civiles et littéraires du XVIIIe siècle.” He probably had a few enemies, indeed—he was, furthermore, a fiery young man with a contradictory spirit, and his misbehaviour had already cost him his position as a lawyer.

“There’s nothing remarkable about his memoirs,” states the stern Dictionnaire historique of Chaudon & Dandeline (Lyon, 1804). As often, this dictionary is wrong. Like a modern Jonas thrown into the belly of the beast, Linguet went through a psychological ordeal—and he renders it with eloquence. In fact, his memoirs are unique, because they give us a description of everyday life inside la Bastille—and no other book of the period does. Furthermore, his memoirs “are essential,” adds Michel Biard, “to whom seek to understand how the myth of la Bastille took on proportions in the 1770s, at a time when the prison was less and less active; as a matter of fact, Louis XVI had approved, in 1784, the project of its demolition—which was never carried out.”

My heart and soul

The French never liked la Bastille, which was built in the 14th century, and became a state prison 300 years later; but Linguet gave it an even worse name. Several modern historians have recently questioned the fantasized severity of the conditions of detention in this prison. But M. Linguet, who almost perished in his tiny, smelly, dark and uncomfortable cell, would probably have a lot to say about that. Anyway, physical pains came second in this purgatory: “La Bastille will tear your flesh apart, only to reach your soul,” he says. Once swallowed up by the beast, the prisoners were denied their very existence, and were never tried. “My experience proves that many men are there incarcerated, whom the state does not wish to judge—and can not judge.”

Being state prisoners, they had no right to communicate with the external world, not even with their relatives, who sometimes remained years without knowing whether their prisoned parent was still alive. Isolated, treated like pariahs, the prisoners lived in limbo. When one of them “had the privilege to be heard by some inspector”, he was taken through the corridors of the prison; yet he “found nothing on his way but silence, deserts and darkness.” Worse, life fled from him as he passed like a ghost: “A dull croaking from the warden chases every living thing that the prisoner could have seen—or that could have seen him. The curtains of the kitchen or the blinders of the windows of the staff building (...) are drawn and shut when he arrives.” There was a time when the prisoners were granted the right to freely walk on the terraces of the towers; but these were the good old days. In the time of M. Linguet, there was only one place they could walk around, the inner yard of the castle. “It is a small square, surrounded by walls more than a hundred feet high, with no window. So that it resembles a deep well where cold becomes unbearable in winter, because of the freezing wind hurling into it; in the summer, the heat is terrible—the sun turns the yard into a baking oven.”

The Cabinet

The prisoners went to the walk one after the other, so that they remained permanently alone. There, sentinels and “a universal silence” surrounded them. Except when someone from the outside—a carpenter, some supplier, etc.—crossed it. “When a stranger arrives,” says Linguet, “we are forced to run to what we call the “Cabinet”: a 12 feet-long and 2 feet large corridor, dug into an old vault. We are required to shut the door behind us, and the slightest suspicion of curiosity leads to the suppression of the walk. These intrusions are frequent.” And most of them had nothing to do with state secrets—including when it regarded the bath of the Governor’s wife. “The bathroom of Madam being inside the castle, she needs to cross the yard to get to it—so do her lackeys, who carry the buckets of water; as well as her “femmes de chambres”, who carry the shirts, the towels and the slippers of Madam; everything would be lost, indeed, should a prisoner take a look at all these state secrets! Here comes Madam herself! She isn’t light; she walks slowly, she has quite a way to go; the zealous sentinel shouts “To the Cabinet!” as soon as he sees her; we have to run until Madam reaches her bathroom.” One day, the sentinel forgot to give the signal and Linguet caught a glimpse of “Diane in her negligee”; the sentinel was sent to jail for eight days. State secrets were no plaything.

Sartine’s clock

There was also a clock, overlooking the yard. Linguet hated it: “Guess what is the ornament of this clock?” he asks. “Some finely carved irons!” A man and a woman, both chained, thus look at the unfortunate prisoner, and “a huge inscription in golden letters engraved in black marble, tells him that he owes this clock to Mr. Raymond Gualbert de Sartines.” Sartines (1729-1801) was the lieutenant general of police.**

Linguet gives interesting details of everyday life in la Bastille. Only a few could assist to the mass—in a Chapel, located under the dovecote of the Lieutenant of the King, some tiny alcoves awaited the prisoners, who could watch the celebration through a wire netting. “I felt so ashamed and miserable that I never wished to go back.” The prisoners could confess, too. “This is but a trap, a joke! shouts Linguet. How dare they suggest you to open your soul to a coward and corrupt preacher, who is prostituting his office.” And when a prisoner died in la Bastille, his body seemed to vanish. “One thing is for sure, it is never returned to his family.”

The size of the gun

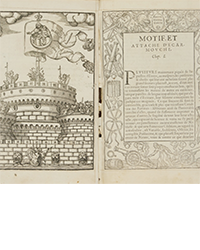

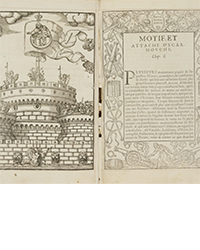

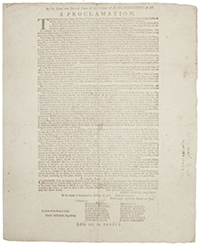

Linguet was eventually released, on condition: “Despotism, which turns silence into a torment inside la Bastille, wants to turn it into a religious duty outside; all the “Jonas” are forced to swear they will never reveal, directly or indirectly, anything they learnt or suffered during their imprisonment.” That’s why he went to London to publish his memoirs. The first edition, dated 1783, comes with a striking frontispiece: some freed prisoners kneel at the feet of a statue of Louis XVI, which kindly stretches his hand towards these grateful creatures—a somewhat obsequious scene as Linguet was careful never to blame the King for his turpitudes, but the “ill-intentioned” people around him instead—he had learnt to be suspicious. In the background, we can see Sartine’s clock, hit by a bolt of lightning.

Six years later, la Bastille was indeed destroyed by “a bolt of lightning”: the French Revolution. Linguet’s book played its part in this historical event. La Bastille had become the symbol of a rogue regime, using the institutions for the sake of a few privileged rather than to protect the citizens. “If the Bastilles of France are not filled with guilty people, then who are these prisoners?” asks our author. “Do we have to tell? All this tyranny falls upon peaceful fathers and irreproachable citizens.” Linguet’s book, laying on a shelf in 2017, may look quite insignificant. But in its time, it came out of the press like a bullet from a musket, aiming at the belly of the Ancien Régime—and it hits its target. “Reading these memoirs,” confirms Michel Biard, “will help to understand how the 14th of July 1789 (the day la Bastille was taken—editor’s note) (...) became a key event in the summer of 1789—a symbolic one, which has been holding a special place in the collective imagination of the French for the past 200 years.”

Linguet—who was born on a 14th of July—came back to France, where he was eventually beheaded on June 27th, 1794. Our author, a discreet and modest architect of the fall of the Ancien Régime was convicted of... treason! By a revolutionary court. Regardless of the regime, reasons of state prevail.

* Mémoires sur la Bastille et sur la détention de M. Linguet (Londres, 1783). In-8°, frontispiece, title page, 157 pages.

** This clock, placed on the main wall of the inside building in 1764, was spared on July 14th. It was sold to the foundry of Romilly-sur-Andelle, where it was saved from destruction. After many tribulations, the French government bought the bell in 1989. It is now displayed in a Parisian museum.

![<b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 16:</b> [Austen, Jane]. A handsome first edition of <i>Sense and Sensibility,</i> the author's first novel. $60,000 to $80,000. <b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 16:</b> [Austen, Jane]. A handsome first edition of <i>Sense and Sensibility,</i> the author's first novel. $60,000 to $80,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/9a74d9ff-42dd-46a1-8bb2-b636c4cec796.png)

![<b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633. <b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/8caddaea-4c1f-47a7-9455-62f53af36e3f.jpg)