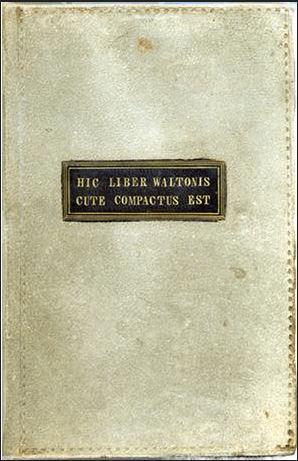

There is, in the vaults of the private library Boston Athenaeum (BA), a peculiar book with a creepy sentence written in Latin on its front cover: Hic liber Waltonis cute compactus est—this book is bound in the skin of Walton. This “skin book”, as it is affectionately referred to, tells the story of James Allen, alias George Walton, a notorious Bostonian highwayman, who died in prison in 1837; a guy who had crime under his skin.

This regular in-8° (25 x15 cm) book of 32 pages is entitled Narrative of the Life of James Allen, alias George Walton, alias Jonas Pierce, alias James H. York, alias Burley Grove, The Highwayman. Being His Death-bed Confession, to the Warden of the Massachusetts State Prison (Boston, 1837). It can be viewed on appointment only, since it is “one of the rarest books in the rare book collection of the Boston Athenaeum, America’s oldest private membership library (it was founded in 1807),” reads the website of the library. It is also available as a PDF file featuring, of course, the front cover—but the rest of the file apparently comes from another unbound copy. The BA is very proud of this curiosity—it is, to be honest, a fascinating and attractive artefact, especially in Boston, said to be “one of the most haunted cities in America.” (Ghosts & Gravestones Boston Frightseeing Tour).

The criminal life of a villain bound in his own skin will sure make you jump out of your skin! But is this story true? “Yes!” the Rialto website affirms, before telling us of a mysterious visitor, who paid the library a visit “a few months ago”: “The visitor’s grandfather, Peter Low, had come to Boston from London, where his father and grandfather were in the book business. Here he was engaged in bookbinding for the Old Corner Book Store and other clients. The grandson relates the story that the skin used for binding Walton’s book came from Massachusetts General Hospital on the very day of his death. Walton was a Jamaican mulatto, and the skin, taken from his back, had been treated to look like a greydeer skin.” Did the binder sign his work? The BA says nothing about it, and it is quite unlikely: “Peter Low had not realized at first the precise nature of the material placed in his hands. By the time his day’s work was done, however, he was in great distress of mind and nightmares filled the night that followed.” Oh boy, just like in a Gothic novel!

The society of the depraved

James Allen, alias George Walton, was a petty thief. Orphaned at a young age, he grew up on his own, in an unfriendly world. Things got worse when he was first incarcerated in October 1824, aged 15, for stealing a bundle of cloth: “In a short time, (...) jail scenes and the society of the depraved and vicious became familiar, and I lost, in a good degree, the tender feelings which influenced me on being first committed.” As a matter of fact, he mentions one Purchase, a jail mate incarcerated for burning his grandmother alive—for he’s a jolly good fellow! Released, he teamed up with William Ross, in Boston. “He was a famous rogue, and was afterwards executed in Canada (...) for robbing a priest,” he says. Under such tutorship, Allen became a regular burglar and highwayman—but he avoided killing people, unless necessary. Allen had principles. “No one but a coward would take human life,” he says. “Except in self defence (...); and even if I was robbing a man, and found it necessary to kill him in order to save my own life, I should not think it wrong; it would be merely acting in self defence”—for he’s a jolly good fellow!

In 1825, Allen was back to prison. But “I suffer nothing, if possible, to trouble my mind.” In 1831, he was sentenced to 2 years of hard labour in the State prison, where he “enjoyed the opportunity of reading many books, principally of moral and religious character.” Yet he made it clear in his memoirs that he “did not intend to lead an honest life. On the day of my discharge from prison, I purchased (…) a pair of pistols, of six inch barrel.” Shortly afterwards, while operating near the Salem Turnpike, he pointed them at one John Fenno, whom he intended to rob. Yet, Mr Fenno fought back, forcing his aggressor to shoot him—“not intending, however, to kill him”; though it looks like an obvious case of self-defence, doesn’t it? The victim suffered but a minor injury; yet his act of bravery “impressed Allen so much that he asked to have a copy of his memoir bound in skin from his own back and presented to Fenno.” How lovely! In fact, according to the catalogue of the BA, Fenno went to see Allen in jail before he passed away. “Soon after, possibly at Fenno’s urging, Allen began to narrate his story.” Their sources? A series of letters owned by the library between the librarian of the Boston Medical Library, John A. Fenno, and the grandson of John Fenno. Despite their accuracy, they are dated November through December 1921, almost a century after the events. On the other hand, that would explain why Allen sent this scary copy to Fenno.

A consumption terminated his life in 1837

The story of the “skin book” seems relevant enough. But some questions remain unanswered. For instance, the narrative of James Allen abruptly stops at page 30: “At this stage of the narrative, Walton becoming subject to a severe cough, and feeling unable to continue any further dictation,” resumes the narrator—the warden of the Massachusetts State Prison—, “requested it might be finished by those to whose authority he was subjected.” After a while, Allen “was admitted as a patient in the hospital, affected with influenza. It finally settled with a consumption, which terminated his life on the 17th of July, 1837.”

But how come he never mentions his desire to send his memoirs to Fenno—or that he dictated them on his demand? No doubt, that would have been an interesting thing to write. Not a word about his skin either. The catalogue of the BA gives further details: “Before his death, Allen asked that enough of his skin be tanned to provide bindings for two copies of these memoirs, one for John Fenno, Jr., and the other for his attending physician, Dr. Henry I. Bowditch. (...) A sufficient piece of skin was removed from Allen’s back and taken to a local tannery, where it was treated to look like grey deerskin and finally delivered into the hands of Peter Low.” But how did it end up at the BA? “Our records do not contain any precise information (...) about when it entered the collection,” confesses the catalogue. “Anecdotal sources suggest that this copy was John Fenno’s and that it was presented to the Library sometime before 1864 by his daughter, Mrs. H. M. Chapin.” So what about the story of Low’s grandson? This point is dubious, to say the least. Rialto’s website reads, in 2011, that Low’s grandson came to the library “a few months ago”. But such a scene should have taken place, if it ever did, in the late 19th century. At the end of the day, can we be sure that we have here a book bound in human skin? No matter how hard it might be to admit, it is very hard to tell a human skin from a goat one.

Bound in the skin of women’s breasts

Several other books are supposedly bound in human skin. One from the Wellcome Collection, London, was, according to a handwritten note slipped inside, bound in the “tanned skin of the Negro whose execution caused the war of Independence*”. But it turned out that it was not the case. Their online catalogue confirms: “Originally thought to be an example of anthropodermic bibliopegy (human skin binding). This is now known to be false.” On the contrary, Rambert, a French murderer, definitely had his memoirs bound in his own tattooed skin in the 1930s. The remains of the English murderer William Burke were also extensively exploited—his skeleton is still displayed at the University of Edinburgh. Shortly after his execution, in 1829, “there was a public dissection and it was reported that part of the skin went missing and then soon after this book turned up for sale in Edinburgh," declared Emma Black from the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh's museum to the BBC, which is no proof.

During the French Revolution, some books were allegedly bound in the skins of some beheaded Nobles—the revolutionaries loved to make pants with their skins, as it seems. The rumor had it that a tannery was then opened to deal with those specific skins. We know about at least one copy of the French Constitution (1791) bound in human skin—it is to be found at the Carnavalet library, Paris. The French bookseller from the Librairie Heurtebise recently drew an extensive list of various books bound in human skins. Among other things, he writes: “There are several attested erotic books bound in the skin of women’s breasts, the nipples being used as decorative elements.” Beauty is only skin deep, as they say.

Human flesh bindings do exist. They instill fear, disgust and fascination into our—yet living—hearts. As such, they have always been surrounded with mystery, suspicion and sometimes forgery. There are as many ways to attract attention as to skin a cat.

* A reference to Cripus Attucks, the first man killed by the British during the Boston Massacre (1770).

© T. Ehrengardt

Boston Athenaeum: www.bostonathenaeum.org

The University of Edinburgh: www.ed.ac.uk/biomedical-sciences/anatomy

The Wellcome Collection: catalogue.wellcomelibrary.org/record=b2124384

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> ROALD AMUNDSEN: «Sydpolen» [ The South Pole] 1912. First edition in jackets and publisher's slip case. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> ROALD AMUNDSEN: «Sydpolen» [ The South Pole] 1912. First edition in jackets and publisher's slip case.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/0a99416d-9c0f-4fa3-afdd-7532ca8a2b2c.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> AMUNDSEN & NANSEN: «Fram over Polhavet» [Farthest North] 1897. AMUNDSEN's COPY! <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> AMUNDSEN & NANSEN: «Fram over Polhavet» [Farthest North] 1897. AMUNDSEN's COPY!](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/a077b4a5-0477-4c47-9847-0158cf045843.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> ERNEST SHACKLETON [ed.]: «Aurora Australis» 1908. First edition. The NORWAY COPY. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> ERNEST SHACKLETON [ed.]: «Aurora Australis» 1908. First edition. The NORWAY COPY.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/6363a735-e622-4d0a-852e-07cef58eccbe.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> SHACKLETON, BERNACCHI, CHERRY-GARRARD [ed.]: «The South Polar Times» I-III, 1902-1911. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> SHACKLETON, BERNACCHI, CHERRY-GARRARD [ed.]: «The South Polar Times» I-III, 1902-1911.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/3ee16d5b-a2ec-4c03-aeb6-aa3fcfec3a5e.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> [WILLEM BARENTSZ & HENRY HUDSON] - SAEGHMAN: «Verhael van de vier eerste schip-vaerden […]», 1663. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> [WILLEM BARENTSZ & HENRY HUDSON] - SAEGHMAN: «Verhael van de vier eerste schip-vaerden […]», 1663.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/d5f50485-7faa-423f-af0c-803b964dd2ba.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> TERRA NOVA EXPEDITION | LIEUTENANT HENRY ROBERTSON BOWERS: «At the South Pole.», Gelatin Silver Print. [10¾ x 15in. (27.2 x 38.1cm.) ]. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> TERRA NOVA EXPEDITION | LIEUTENANT HENRY ROBERTSON BOWERS: «At the South Pole.», Gelatin Silver Print. [10¾ x 15in. (27.2 x 38.1cm.) ].](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/fb024365-7d7a-4510-9859-9d26b5c266cf.jpg)

![<b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> PAUL GAIMARD: «Voyage de la Commision scientific du Nord, en Scandinavie, […]», c. 1842-46. ONLY HAND COLOURED COPY KNOWN WITH TWO ORIGINAL PAINTINGS BY BIARD. <b>Scandinavian Art & Rare Books Auctions, Dec. 4:</b> PAUL GAIMARD: «Voyage de la Commision scientific du Nord, en Scandinavie, […]», c. 1842-46. ONLY HAND COLOURED COPY KNOWN WITH TWO ORIGINAL PAINTINGS BY BIARD.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/a7c0eda0-9d8b-43ac-a504-58923308d5a4.jpg)

![<b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 11:</b> Darwin and Wallace. On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties..., [in:] <i>Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnean Society,</i> Vol. III, No. 9., 1858, Darwin announces the theory of natural selection. £100,000 to £150,000. <b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 11:</b> Darwin and Wallace. On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties..., [in:] <i>Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnean Society,</i> Vol. III, No. 9., 1858, Darwin announces the theory of natural selection. £100,000 to £150,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/00d5fd41-2542-4a80-b119-4886d4b9925f.png)