When Theology and Philosophy Meet

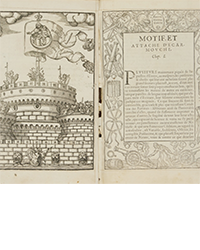

Swinden’s book was very popular—hence the French translation. In fact, it was part of a theological quarrel, summed up by Hasperg, who wrote to Leibnitz in 1714: “Monsr la Roche says in his Memoirs of Literature that a Spanish author is claiming that the sun is the eternal Paradise and shall be the dwelling place of the happy souls, and that Mr Swinden, an English Minister, situates hell in the sun, claiming it is the dwelling place of the devils and the unhappy souls (...). Isn’t it a pleasing dispute? The Spanish author sends the Roman Catholic to the sun, probably exclusive of others, and the English doesn’t want to go there. This English cession is quite prompt, and this dispute over the possession of the sun ended up more peacefully than the one regarding the trade of the world, that lasted for so long, and which was eventually settled to the advantage of the Spaniards, as it seems.” Other writers disagreed with Swinden, including Patuzzi (1700-1769), who published De sede inferni in terris quarenda in 1763 (Venice), to refute his theory.

Theology is like a luring pit of darkness, waiting for our spirits to fall in it. Isn’t it exciting to wonder about the Creation? For example, shouldn’t God take, after a (long) while, the tormented souls out of Hell? The ancient theologian Origen (185-253) thought so, as such a disproportionate punishment seemed opposed to God’s legendary meekness. As far as Swinden is concerned, hell is a place of no return! And also, how could the sun be both a positive thing—as the Bible says—and the dwelling of Lucifer? And is the divine fire made of the same substance as the ‘regular’ one? So many questions to query, yes... But beware! As Duvernet puts it: “We could talk for years about all these things, and yet say nothing of interest.”

As a matter of fact, the four founding fathers of theology in France were called “the four labyrinths.” Dozens of thousands of people have spent their lives roaming these labyrinths only to end up in a dead end. At least, these wretched and genuine theologians really tried to unravel the mysteries of the Creation; others used theology as a social weapon. Duvernet says: “It is with the help of theology that our bleak preachers, once living in a Biblical poverty and humility, have become powerful in honour, in credit (...) and in riches (...). It is with the help of the same theology, and by the illusions of these thinkers, that (...) the Church has kept its riches, increased by the ever revived fables of the coming of the Anti-Christ, of the imminence of Judgement Day; by various and infinite lies about Paradise, Hell and Purgatory.” Let’s notice that these lines were published in 1790, once “reason and courage had had the better of the walls of La Bastille”—meaning after the French Révolution of 1789. This was the triumph of reason over theology, when all the bizarre theories that had sustained the workers of iniquity for so long were eventually cast into the dark pits of... the sun?

Among the many archangels who fought this war, Voltaire (1694-1778) was no doubt the most influential of all. His bitter remarks over the many inconsistencies of the Bible and the theologians’ reveries brought the Church to its knees. All these fancy stories about Heaven and Hell were sure below his intelligence. Yet, he apparently understood the social importance of misleading the masses: “We are facing many rascals with little understanding,” he writes in his Philosophical Dictionary, “a lot of little people, being brutal, drunkards and thefts. Teach them if you please that there is no hell, and that the soul is mortal. As far as I am concerned, I will yell at their very ears that they shall be damned if they rob me.” Lord, what a weeping and a gnashing of teeth when Swinden and Voltaire meet!

(c) Thibault Ehrengardt

![<b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 16:</b> [Austen, Jane]. A handsome first edition of <i>Sense and Sensibility,</i> the author's first novel. $60,000 to $80,000. <b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 16:</b> [Austen, Jane]. A handsome first edition of <i>Sense and Sensibility,</i> the author's first novel. $60,000 to $80,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/9a74d9ff-42dd-46a1-8bb2-b636c4cec796.png)

![<b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633. <b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/8caddaea-4c1f-47a7-9455-62f53af36e3f.jpg)