Paul Krugman in his book The Conscience of a Liberal, published in 2007, describes the economic history of America since the Civil War as a succession of changing perspectives on taxation. This led me to wonder if tax rates, which are unusually low today, are having an impact on book collecting and rare book valuation.

The Gilded Age that emerged in the 1870s and that lasted until the Great Depression was a time where wealth was highly concentrated, easily maintainable, and not taxed on the top 10% of taxpayers at unusually onerous rates. During the Depression, after FDR became President, his goal became to radically shift wealth back to the masses though the gradual escalation of tax rates. This lead over the next three decades to greatly elevated tax rates on the wealthy, eventually topping out at nearly 80% around 1955. Twenty-five years later, Ronald Reagan undid this high tax paradigm, replacing it with a two-tiered approach that reduced the rates for all taxpayers but particularly reduced the rates on high incomes. These tax cuts, now embedded in the American tax system, continue to vastly favor the wealthy. As a result, the percentage of assets held by those with the highest income has soared while income earned by the middle class has eroded.

In a comparison between tax rates and rare book pricing as expressed in AE’s auction outcomes over the past 150 years, it is difficult to correlate prices and tax rates in the United States in any of these periods, at least in part because other events consistently intervened; in particular, the Great Depression followed by World War Two, both extraordinary economic periods of stimulus, with the war years also a period of enforced personal saving. Post WW2, these earnings surged into the economy providing a solid ten years of economic stimulus and creating an enormous middle class that often used the GI Bill to attend college, thus supporting and encouraging institutions to build monumental libraries with vast and important special collections that over the next fifty years would dominate rare book acquisition.

Today such broad based rare book acquisition is in decline, many institutions now maintaining but no longer aggressively building their collections. Their focus has shifted to gifts, narrowing collections and repurposing facilities.

Since the early eighties in addition to lower tax rates we also have seen the rise of the Internet, the extraordinary connectivity tool that makes inventories and the contents of printed material accessible. Both aspects have transformed the world of old and rare books. Whether declining tax rates or increasing access is the most important factor is unclear. Databases such as Abe Books now warehouse the descriptions and prices of material from all over the world – permitting in a few keystrokes the searching of more than a hundred million books that are available for purchase. As well, Google Books and others now provide full access to the texts of out of copyright material.

These changes have then led to a redefining of what is rare and also made it appropriate to ask librarians if their job is to provide fully searchable text or the original printed texts. About ten years ago librarians by a margin of 70/30 said their job was to provide the searchable text. A few years ago the numbers shifted to 85/15, and one well-placed dealer said the numbers were shifting to 90/10. The role of rare books is changing.

The cost to maintain such collections is also rising, while the flow of visitors is declining. The costs of rising security, preservation, and personnel are now being gauged against traffic that is falling as researchers increasingly use electronic access to full texts rather than make time consuming and sometimes expensive trips to view printed copies first hand.

This will eventually lead to the dismantling of many library collections. Not all, but many will be redistributed within the library world and/or sold to dealers or sent to auction. The cost of maintaining such libraries is becoming too high to justify the many related and unavoidable expenses that are attendant to such collections so it seems a certainty that many will be disposed. But the stages of acquisition, holding, refocusing, and dispersal will be measured in decades, not years. Most of what will happen will happen well into the future, and the reasons seem less to do with economic periods than with increased information and changing technologies that recalculate the access/ownership equation and increasingly favor access over object. This suggests a tsunami of new collectors will be needed over the next twenty years to offset library outflows, something I think is achievable because collecting possibilities have probably never been better.

But how do we make the case to the book collectors of tomorrow once they are identified? It will require every hand; the booksellers associations, the auctions, the listing sites, the libraries, and the rare book research sites all to play their part. Those involved with old and rare books understand its power. The challenge is to convey that power.

In 2015, and in the years ahead, we need to make that case clearly and with conviction. It will be an act of kindness to them and to ourselves.

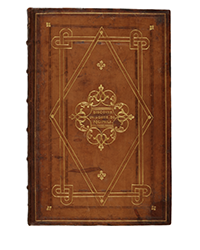

![<b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 16:</b> [Austen, Jane]. A handsome first edition of <i>Sense and Sensibility,</i> the author's first novel. $60,000 to $80,000. <b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 16:</b> [Austen, Jane]. A handsome first edition of <i>Sense and Sensibility,</i> the author's first novel. $60,000 to $80,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/9a74d9ff-42dd-46a1-8bb2-b636c4cec796.png)

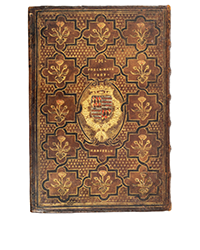

![<b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633. <b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/8caddaea-4c1f-47a7-9455-62f53af36e3f.jpg)