A record price has apparently been paid for a photograph – a whopping $6.5 million. We say “apparently” as it was a private sale, and it is impossible to know for certain whether there has been a larger such sale in the past, though it is quite unlikely. This was not a picture from the dawn of photography, a photographic equivalent of a Gutenberg from Daguerre's Brownie. It is a fairly recent photo from the camera of Peter Lik, a photographer who melds scenic views with art. He is sort of a contemporary Ansel Adams, except he isn't afraid of color. Ironically, the winning photo is a black and white, perhaps a bow to Adams.

The photograph is titled Phantom, and it was taken in Antelope Canyon, Arizona. The canyon is on Navajo land, near Page, Arizona, and the Utah border. It is a spectacularly scenic canyon, and at this particular spot, an opening above the walls enables a shaft of light to penetrate to the floor. In this shot, dust within the shaft of light creates a ghostly image, the “Phantom.” It is a black and white version of the photograph Ghost.

Speaking of his photography, Mr. Lik said, “The purpose of all my photos is to capture the power of nature and convey it in a way that inspires someone to feel passionate and connected to the image.”

The buyer has chosen to remain anonymous, but is already a collector of Lik's photographs. He was represented by a Los Angeles law firm, which may or may not tell us something.

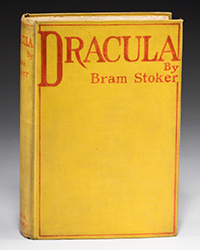

This sale is an important milestone even for a site about books. It taps into two major trends within the field, which is evolving and expanding. The field is becoming more one of “works on paper,” rather than just traditional “books” alone. Whether it is what dealers are selling or collectors collecting, we find pamphlets, broadsides, manuscripts, photographs, prints, and other forms of ephemera added to the mix. Collectors today often desire objects that can be hung on a wall to complement those that are placed on a shelf.

The other trend is to the concept of “books as art.” Books are functionally a vehicle for ideas, which is usually expressed in text. However, even as far back as Gutenberg, and you can't go farther back then that in the world of printed books, his type was designed to be aesthetically appealing, rather than simply relaying words. This soon expanded to beautiful bindings. Barely a half century after Gutenberg, the most famous of collectors of fine bindings, Jean Grolier, began having his books bound as works of art, rather than of function.

Late in the 19th century, spurred on by William Morris and his Kelmscott Press, we saw the development of the private, fine press movement. The focus of the private press works was the artistic qualities of the book – type, colors, paper, etc., rather than the underlying text, which often would be a familiar title readily and inexpensively available in ordinary-looking editions for those who wanted to read them. If anyone ever tried to read a Kelmscott Chaucer, the immediate question would be, “why?”

The melding of different forms of works on paper, art, and books can be seen in the forms in which Mr. Lik makes his photographs available. For those who can afford $6.5 million, a standalone photograph is an option. For those not quite so financially endowed, Peter Lik's photography can be enjoyed in the books of photographs he has published. Yes, Peter Lik is an “author” too, even if he lets his images do most of his speaking for him.

Book collecting may not be quite as widespread today as it once was. Technology and a desire for the visual have, if not changed our interests, certainly broadened them. Books today are more likely to be part of a collection rather than the collection. It's all good. There is room for everyone. Peter Lik can publish books, and book readers can appreciate art and other forms of paper. And, who could look at a Lik photograph of a beautiful scene and not want to read more about that spectacular place?

Peter Lik's books of photography are available on his website: www.lik.com/shop/books.html.

![<b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 11:</b> Darwin and Wallace. On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties..., [in:] <i>Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnean Society,</i> Vol. III, No. 9., 1858, Darwin announces the theory of natural selection. £100,000 to £150,000. <b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 11:</b> Darwin and Wallace. On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties..., [in:] <i>Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnean Society,</i> Vol. III, No. 9., 1858, Darwin announces the theory of natural selection. £100,000 to £150,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/00d5fd41-2542-4a80-b119-4886d4b9925f.png)

![<b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633. <b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/8caddaea-4c1f-47a7-9455-62f53af36e3f.jpg)