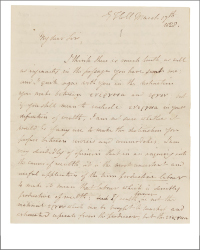

The Alta California,

Washington street, Portsmouth Square.

TERMS—One dollar a number, with an allowance of 124 per cent, to purchasers of not less than 25 copies. Half yearly subscription, in advance, $10.00 ADVERTISEMENTS will be inserted at the usual rates.

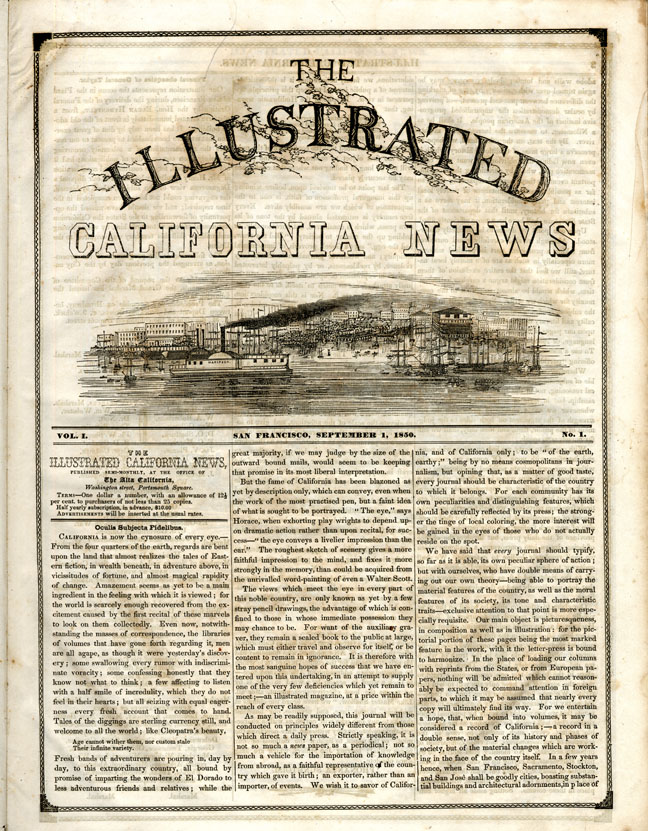

CALIFORNIA is now the cynosure of every eye.— From the four quarters of the earth, regards are bent upon the land that almost realizes the tales of Eastern fiction, in wealth beneath, in adventure above, in vicissitudes of fortune, and almost magical rapidity of change. Amazement seems as yet to be a main ingredient in the feeling with which it is viewed; for the world is scarcely enough recovered from the excitement caused by the first recital of these marvels to look on them collectedly. Even now, notwithstanding the masses of correspondence, the libraries of volumes that have gone forth regarding it, men are all agape, as though it were yesterday's discovery; some swallowing every rumor with indiscriminate voracity; some confessing honestly that they know not what to think; a few affecting to listen with a half smile of incredulity, which they do not feel in their hearts; but all seizing with equal eagerness every fresh account that comes to hand. Tales of the diggings are sterling currency still, and welcome to all the world; like Cleopatra's beauty,

Their infinite variety.

Fresh bands of adventurers are pouring in, day by day, to this extraordinary country, all bound by promise of imparting the wonders of El Dorado to less adventurous friends and relatives; while the great majority, if we may judge by the size of the outward bound mails, would seem to be keeping that promise in its most liberal interpretation.

But the fame of California has been blazoned as yet by description only, which can convey, even when the work of the most practised pen, but a faint idea of what is sought to be portrayed. "The eye," says Horace, when exhorting play wrights to depend upon dramatic action rather than upon recital, for success—" the eye conveys a livelier impression than the ear." The roughest sketch of scenery gives a more faithful impression to the mind, and fixes it more strongly in the memory, than could be acquired from the unrivalled word-painting of even a Walter Scott. The views which meet the eye in every part of this noble country, are only known as yet by a few stray pencil drawings, the advantage of which is confined to those in whose immediate possession they may chance to be. For want of the auxiliary graver, they remain a sealed book to the public at large, which must either travel and observe for itself, or be content to remain in ignorance. It is therefore with the most sanguine hopes of success that we have entered upon this undertaking, in an attempt to supply one of the very few deficiencies which yet remain to meet;—an illustrated magazine, at a price within the reach of every class.

As may be readily supposed, this journal will be conducted on principles widely different from those which direct a daily press. Strictly speaking, it is not so much a news paper, as a periodical; not so much a vehicle for the importation of knowledge from abroad, as a faithful representative of the country which gave it birth; an exporter, rather than an importer, of events. We wish it to savor of California, and of California only; to be "of the earth, earthy;" being by no means cosmopolitans in journalism, but opining that, as a matter of good taste, every journal should be characteristic of the country to which it belongs. For each community has its own peculiarities and distinguishing features, which should be carefully reflected by its press; the stronger the tinge of local coloring, the more interest will be gained in the eyes of those who do not actually reside on the spot.

We have said that every journal should typify, so far as it is able, its own peculiar sphere of action; but with ourselves, who have double means of carrying out our own theory—being able to portray the material features of the country, as well as the moral features of its society, its tone and characteristic traits—exclusive attention to that point is more especially requisite. Our main object is picturesqueness, in composition as well as in illustration: for the pictorial portion of these pages being the most marked feature in the work, with it the letter-press is bound to harmonize. In the place of loading our columns with reprints from the States, or from European papers, nothing will be admitted which cannot reasonably be expected to command attention in foreign parts, to which it may be assumed that nearly every copy will ultimately find its way. For we entertain a hope, that, when bound into volumes, it may be considered a record of California; — a record in a double sense, not only of its history and phases of society, but of the material changes which are working in the face of the country itself. In a few years hence, when San Francisco, Sacramento, Stockton, and San Jose shall be goodly cities, boasting substantial buildings and architectural adornments, in place of adobe walls and lumber sheds, our pages may be again turned over with curiosity, by way of marking the difference between past and present,—of proving by ocular demonstration the unparalleled progressive instinct of the American people. It shall be as a Nilometer, to measure the increase of a mighty river. By the text, on the other hand, we hope to preserve a large mass of traditional history, which is even now fading into oblivion for want of a commemorative pen, while by chronicling the more important events as they pass, and separating them, so far as possible, from circumstances of merely local interest and party consideration, it may serve as a substitute for history, until that department of the State literature shall have been more efficiently filled.

Upon one point we desire to be distinctly understood. Although we shall carefully guard ourselves from taking a prominent part in political matters, more especially in such as are of a merely local nature, still we feel that the entire exclusion of them from consideration might argue a careless indifferentism, which would be almost an affront to the community for which we write. Systematically to reject the subject, confining ourselves to descriptions of locality and literary disquisitions, would throw a damp upon our pages, a flatness of effect, that no power of language, or refinement of style could overcome.— To use a homely, but expressive phrase, it would be offering "porridge without salt.".

Whenever we happen to believe ourselves capable of subjecting a broad question to the test of logical reasoning, not in the spirit of advocacy or partisanship, but in style of a judicial summing up;— whenever we see a chance of presenting the full strength of the argument on both sides to the judgment of the public, then, and then only, shall we suffer ourselves to speak.

With regard to party, we link ourselves with none, and interfere with none. Of course we cannot be without our own private political predilections; no man whose blood runs warm in his veins, who has a spark of social feeling or impressionable temperament about him, can venture to believe himself entirely free from party bias; we shall nevertheless make a point of suppressing it, inasmuch as that the expression of any such feeling not only intrudes upon the province of the daily press, but involves the chance of being drawn into controversy, a challenge which we shall resolutely decline to entertain. We shall endeavor to keep a straight forward course, casting off to the right and left, as irrelevant, every thing that does not directly tend to the advancement of the State.

Our claim to attention shall be based on the most rigidly punctilious regard to accuracy of fact.— Hackneyed as we are in public writing, swept along as we have often been in the full tide of the bitterest political controversy, we pride ourselves upon having never published a single line in the truth of which we did not religiously believe. There is no vain glory in the boast; any one can acquire a right to make the same, if he have only the will to win that right. We may be mistaken from time to time,— led astray by placing over-ready confidence in statements that we are unable to verify by personal experience; but will vouch for guarding as far as possible against every such mishap, by care in the selection of correspondents, and close comparison of opposite accounts. No monster gold stories, no ex parte statements, no crying up of one location at the expense of another, nothing but what shall have been first touched with the spear of Ithuriel, will ever fine place in these colum[n]s. Setting aside all higher considerations, we firmly believe that it is the ultimate interest of a public journal to keep this principle uppermost in view. In spite of the Hudibrastic warning, that

The world is naturally averse

To all the truth it sees and hears;

But swallows darkness, and a lie,

With greediness and gluttony;

we are still convinced that the confidence of the pubic is the first object to secure, and that the public will not be long in finding out where that confidence may be securely placed.

The last point to be touched upon, before winding up this inaugural profession of faith, is one to the importance of which we are sensibly alive. Every free country is estimated abroad by the tone of its own press, which is considered, not unreasonably, as holding up the mirror to society. "Bad the crow, bad the egg," says a Greek proverb, of immemorial antiquity; and wherever journalism is marked by violence, by recklessness, or by palpably interested motives in expression of opinions, the blame will be justly attached, not so much to itself, as to the community that supports it. Nor is this consideration, that it is not the sole sufferer by its own misdeeds, the only one to be kept in prominent view. "Upon the press of this country," observes the writer of a very remarkable article in the Marysville Herald, "rests a great responsibility. For good and evil it has a great power. The newspaper, therefore, should be more than a price current of the markets, a reporter of crimes and events, a chronicle of gold diggings, or a 'snapper up of unconsidered trifles.' It should be the book from which may be drawn instructions and incentives to those moral and social qualities, which will more than any thing else tend to elevate the scale of the affections, and give to society in California that character which can alone secure its permanency as a State." Let us therefore pledge ourselves—so far as ability may allow—to make common cause with our elder brethren of the craft in supporting the principles, and working out the precepts, so eloquently insisted on in the article from which we quote; in maintaining a high standard of writing, both as regards morality, dignity of expression, and abstinence from unnecessary personalities. And though it beho[o]ves us to be chary of engaging for performance, we may safely promise never to offend.

Let it not therefore be supposed that we intend to indulge in lecturing, or to be guilty of any such unwarrantable assumption. "Never moralize without spectacles," quoth Doricourt in the Belle's Stratagem, to a tiresome adviser, with more practical wisdom in a single phrase than the other could command in the length of a sermon. To be merry as well as wise :—

Polla men geloia ei-(why is there no Greek type to be had in California?) after the fashion of Aristophanes, who doubtless had his private reasons for the commixture of style which he adopted when addressing an Athenian audience— to back a word in season by a word in jest, is by no means the least effective preachment, after all. Like Master Shallow, "we have heard the chimes at midnight" in our time, and promise our heartiest thanks to any one who will enrich us with a characteristic anecdote, or racy witticism, "fire-new from the mint," or the mines, to lighten the dullness of our pages withal; barring Joe Millers, which are long since obsolete.

pein, polla de spoudaia,

![<b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633. <b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/8caddaea-4c1f-47a7-9455-62f53af36e3f.jpg)