The following is a text version of a talk I gave at the California Rare Book School and the Book Club of California on Monday 4.

Printing in the western world is an old thing. It traces to Gutenberg’s development of movable type, his first examples printed around 1440 and the most famous book ever printed, the Gutenberg Bible in 1454. It was a remarkable moment as moveable type opened a path to the printing of multiple copies. Early printing had a strong artistic component but the potential to communicate widely soon repurposed the invention leading toward efficient communication of ideas and information. For the next 250 years literacy rates would remain low but the utility of reading become firmly established.

Until the mid-18th century most people in England, the birthplace of the industrial revolution, engaged in subsistence farming. Those said to be literate mostly met a simple standard far below what we understand literacy to be today.

With improving farming techniques and a correspondingly greater food supply children in the mid 18th century began to live further into adulthood, some becoming excess to the requirements of maintaining family farms and plots from one generation to the next. Family size would fall by the late 18th century but not as quickly as farm output increased. Inevitably some children were encouraged into other endeavors and gradually cities became the destination of many. The times were auspicious, the increasing food supply produced by an ever smaller farm population, setting the stage for the industrial revolution.

In cities idle hands, wanting for food, provided a steady supply of cheap labor. Experiments in rudimentary manufacturing led to rising production through the substitution of increasingly complex machines for repetitive mechanical processes. These changes in turn required a better-trained work force. Education became entwined with economic advance and over time the English working class became its middle class, emerging first as process workers and later as builders of the efficient machinery that transformed national economies around the world in the 19th century. Less noticed in the changes sweeping the country, the emergence of libraries, book collectors and booksellers were the byproducts of increasing education and rising economic stability. ˜It was a trend that would take hold and in time sweep the world. Books, essential to the exchange of information, were sometimes also collectible. Every family had them and almost every family kept them safe and valued.

The success of the English economy brought moderate wealth to the middle class and it was this portion of England’s population and the populations of many other advancing countries that would make book collecting a respected field dependent more on intelligence and intellectual diligence than financial capability. Books were interesting, sometimes complex, often bibliographic jigsaw puzzles. They were satisfying to own and widely appreciated, interesting and complex but not terribly expensive. Great collections would be built with determination rather than money and many were.

Wars would ravage periodically and economic uncertainties plague the western world. In the pre-Keynesian world economic bubbles and collapses happened regularly and there seemed little could be done to avert them. Keynesian thinking and the post-Keynesian world embraced compensating government action to offset periodic economic decline.

This change created a more stable world and one that increasingly permitted the building of great collections, most of them by stalwarts of the middle and upper-middle class, this possible because the distance between the middle class and the top of the economic pyramid, while significant was, as late as the 1960s, only about 40 times, that is the difference between the janitor and the company president 40 times.

In the post World-War II period a surge in higher education brought wealth to colleges and universities and an outpouring of desire among faculty and administration to have great libraries and great collections. For the rare book business this was the beginning of an exceptional era, one of steep imbalance between supply and demand and lead, over the next 40 years, to prices achieving unimagined and ultimately unsustainable levels. The rise would be exhilarating, the decline unnerving, today unfolding into what is turning out to be a perfect storm of rising online visibility of full texts and copies for sale, declining institutional purchases, and a lost generation of collectors for whom collecting opportunities often never sufficiently materialized between 1970 and 2000 to impassion them to fight over and for the never imagined fresh heaps of material that drift into the market every quarter now.

In the 1990s, for dealers in the mid-range and lower, the chickens would come home to roost. Higher prices began to bring more copies out and it became difficult for sellers to maintain the illusion of ever-higher prices in the face of declining institutional interest and weak collector demand. Material in this sector held but volume declined until the Wall Street crisis in 2008 broke the decades-old 10-7 relationship between retail prices and auction realizations leaving us today with a 10-5 reality for solid but otherwise unremarkable copies that are common today.

This has left the market casting around for a direction and propelled a strong trend among dealers to refocus on unique material for which price is less defined by auction realizations. For premium dealers the adjustment has been less. Many, for a decade, prepared for what to them seemed obvious, that the markets for the best material would continue to prosper while the mid and lower levels fall into a buyer’s bonanza that is now daily re-defined in the auction rooms.

For less than exceptional material overall we are now in the stage where broad categories, once thought to be valuable only because no one would sell theirs’ cheaply, now find such material regularly re-priced in the auction rooms at steep discounts and attracting the serious interest for the first time in years.

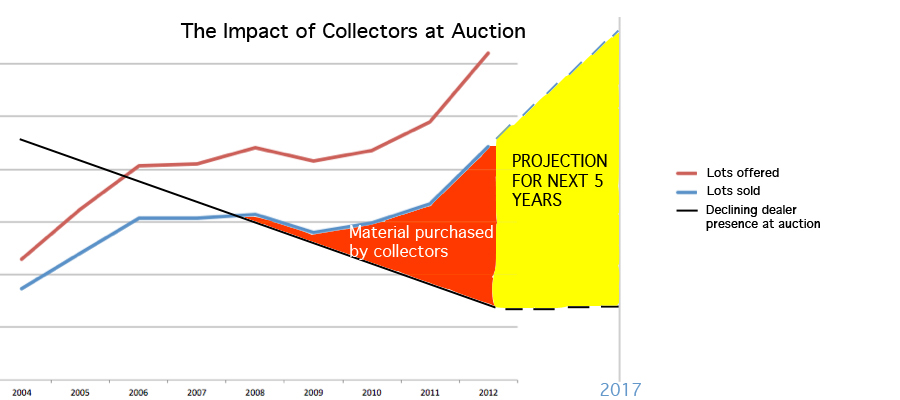

Lower prices are having a positive effect. Buyers who years ago grew cautious now increasingly buy at auction. Auction volume has surged, increasing on average around 15% a year over the past decade. Through this period dealers have been boarding up shops while new auction houses have been opening and existing firms adding events and increasing the size of their sales. It feels as if the shift portended for years, and only recently a trend, is becoming permanent. Price it turns out matters.

The number of lots passing through the rooms seems destined to further increase and I have prepared a chart of what I think may lie ahead. Most booksellers hope to quickly sell but are prepared to wait for the buyer willing to pay up. But older booksellers facing the additional issue of declining time are being forced to decide now because it takes time to wrap up a rare and used book business, the probable number now north of five years. Those that adjust pricing aggressively now stand a reasonably good chance to sell in that time. For those who chose to hold the line time may simply run out. This is a field that many have enjoyed but it is not the same field today it was when today’s greys and whites were in their primes.

History suggests that when the bookseller dies, so too often does the community comity that provided reassurance through the tough times. His or her material too will quickly go somewhere, the most desirable easy to place, and the balance to be carted away. Much of it was backdrop anyway. A significant aspect of bookselling has been the dealer’s personality. When that spark is gone there is only the scenery without Othello to command our attention for the best have been and always will be magicians who can summon, as in a time machine, the author and his circumstances as he wrote a book or penned a letter.

The shifting of focus from dealers to the rooms comes at a cost. For decades most collectors’ introduction to the field has come through the ministrations of dealers, who spotting a serious prospect, nurtured such possibilities. Booksellers of substantial intelligence and prodigious memory have always been able to talk birds down from the trees. In their once plentiful shops they had the opportunity to perfect salesmanship in their main street mahogany groves of rare volumes of rich bindings, wonderful illustrations and quaint and appealing histories. Today book fairs are their pale replacements and printed catalogues their less frequent emissaries. The rare book field struggles for better choices.

And the audience changes. Buyers at auction today appear to be about 10 years younger than typical dealer clients and there are many more of them than there used to be. Routinely hundreds of bidders sign-up and many bid at what is becoming a hundred sales a month. Realizations are consistent, less than what dealers ask for mid-level material and comparable for the best. These days the majority of the lots go to collectors and institutions, while the majority of the value goes to dealers who better understand the power of quality and are emerging as what the French style “les experts”. They are

So to the question that has been the burning issue for more than twenty years in the trade, “where are the new collectors?” We have the answer. They are in the rooms in surprising numbers and buying the best material dealers offer and showing a preference for prices confirmed in the marketplace.

As to the future it is difficult to say with clarity. We are at the end of the Gutenberg era and at the beginning of the Google search. Prices became terribly inflated and are returning to earth. We have a taste for printed works. Our heirs too will be collecting but whether they will appreciate what we like is a question yet to be answered.

What we will bequest to them is a market far more efficient than any prior iterations have been. Our contribution may ultimately be that we weathered the dealer – library bacchanalia and have emerged in tact and still in love with the material.

For some dealers the choices will be severe. Many will seek to avoid markdowns, see their sales decline as customers die or are weaned away, and still hold out, maintaining their above the market prices until the bloody end. And this is just as well because too much inventory, too soon, would weight down the market mightily. We estimate that a continuing 15% annual increase in auction volume can be absorbed with little disruption and know this because we have seen steady increases in auction volume for years while prices have remained reasonably steady.

Looking ahead we are in a delicate balance with rising auction volume and an aging dealer population on the one side and an increasingly efficient market on the other, Stalwarts of the passing generation that will sell the way they always have or not at all while an increasing proportion on both sides adjust to the emerging value consensus established in the auction rooms.

We have made it into the new world. All the books, manuscripts, maps and ephemera will too, if not immediately, then in time. Our grandchildren may look back upon our efforts and wonder what it was we liked so much. I hope so and further hope they see it as we have, that there is wisdom and perspective in these old things. About that there should be no debate. That then leaves only one variable to discuss: price.

And this is being established in the rooms as we speak.

![<b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633. <b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/8caddaea-4c1f-47a7-9455-62f53af36e3f.jpg)