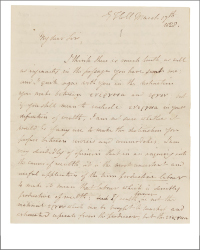

We were fortunate enough to receive a fascinating catalogue published earlier this year by the UCLA Library in Los Angeles, six hundred years in the making, so to speak. Its title is Crime and Punishment in Paris, 1412, and it is the result of much research by Richard and Mary Rouse. The thought of crime and punishment in 1412 sounds like something barbaric, but this is an account of low level crimes, the kind of things a court was more interested in making go away than in exacting severe retribution. It is a picture of the daily conflicts and disputes that go on quietly in courtrooms everywhere today, the sort of things most of us avoid, but others perhaps not so fortunate deal with on a regular basis. It is a record that one would expect long ago to have been lost to history. It would have been but for a fortuitous stroke of good luck.

The story of how this record managed to survive is almost as exciting as the find itself. As the catalogue notes, the record UCLA researchers found is 75 years older than any others from the Chatelet, a prison and court for less serious crimes in Paris in the 15th century. No one thought such records worth preserving. Indeed, they were so little regarded that a bookbinder centuries ago trimmed them down and used them to stuff the binding of another book. That book eventually made it from France to UCLA where, in the 1940s, it was determined it needed to be rebound.

When the old binding was removed, six leaves from the Chatelet records from the spring of 1412 were discovered. The binder thought the pages worthless and tossed them in the trash. Fortunately, an assistant, J.R. McClurkin, found them interesting, retrieved the leaves, and took them home. Forty years later, now retired, McClurkin gave them to UCLA library's special collections. It was there that Richard and Mary Rouse, along with the late John Benton of the California Institute of Technology, identified the leaves. A translation was published in 1999, and now with this catalogue, we have a translation along with detailed information about the settings of the various crimes described.

Since the size of the binding was smaller than the original records, the leaves were trimmed. The result was that some copy was lost. Fortunately, enough remains to get a good look at what was happening in 1412 – what were the lower level crimes, and what was the punishment. The punishment, it turns out, was not severe. Most “criminals” were released either the same day or within a day. One-quarter of the cases were the result of debts, but these debtors weren't being sent off for long stretches in debtors' prison, as happened regularly many centuries later. That may be explained by an interesting twist. The creditor was required to pay the debtor's room and board while in prison, encouraging them to reach settlements and payment schedules with those who owed them money quickly.

The records contain the name of the accused, the arresting officer, the reason for the arrest, and other details of the case, often including its disposition. It is likely that the records provide a look at what typically went on in the court as there are 71 records covering three random dates (April 24-25, May 20-21, and May 23-24, 1412). Here are a few examples from the “people's court” of Paris 600 years ago.

Record #2. Lorin de Clerc, a cobbler, was arrested at the request of Pierre du Fossé. De Clerc had pulled off the cloak du Fossé's wife was wearing and threw it in the mud. Evidently, this was meant as an insult to her, though the reason for this is unknown. The cobbler was held for two days.

Record #4. Since part of the record is missing, it is not certain who brought this complaint, but likely it was Jehan Grimault, a vineyard keeper from the countryside. Apparently, Jehannin Huet, a laborer, not only stole some of Grimault's belongings, but his wife as well. The pair ran off to Paris. Huguette Grimault received the honor of a two-day stay at the Chatelet, while Huet was held for 12 days, and then only freed conditionally (the conditions are not stated).

Record 8. Here is a dispute between two doublet-makers (a doublet was a kind of jacket worn during the Middle Ages). Jehan le Promoteur claimed that Alain du Val had taken a pair of scissors from him. Du Val responded that he wanted to get to the truth of the matter. This was a common response by those accused. Both were released the day of the arrest, presumably the right man in possession of the scissors.

Record #10. Regnaut d'Esply, a servant, was arrested on the request of Jehannette Patin, wife of Laurens Patin. Laurens was a blind beggar, who was given a spot at Notre Dame to pursue his trade. It seems that d'Esply had a scam where he would give a blind beggar some coins but take back in change currency worth more than he had given. He was released on some unstated condition (presumably to return the money and stop doing this).

Record #13. Five ladies engaged in the world's oldest profession were arrested. Prostitution was legal, but only within certain zones, and if carried out in a reasonably discreet manner. These ladies must have created too much of a disturbance, upsetting their neighbors. They were all conditionally released.

Record #32. Henryet du Pré, a servant, was arrested at midnight for breaking down the door of Cardine Sebile, a prostitute, and for wearing a sword. Carrying swords was illegal in Paris, there being no right to bear swords at the time.

Record #44. Robert Charles approached the court, not because he had committed a crime, but to seek absolution for a past one. His past crime was attempted suicide, also illegal in Paris. He had stabbed himself repeatedly with a knife, though evidently not in the right places to accomplish the task. Charles had a letter of pardon from the King, but that needed to be officially confirmed by the court.

Record #49. Guillaume de Saint George, an innkeeper, was taken in on a charge of assault against Jehannin Coiffart. However, Saint George did not assault Coiffart. His wife, Perrette, did. Evidently, Coiffart believed Saint George needed to do a better job of keeping the little lady under control. The court must not have been too upset by his role because despite this charge and one of renouncing God, Saint George was set free the same day.

If Jerry Springer were around in 1412, he probably would have had a field day with the Chatelet. They dealt with lots of disputes that would have made great fodder for afternoon television. If there is one conclusion to be drawn from these 600-year-old records, it is that the more things change, the more they remain the same.

![<b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633. <b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/8caddaea-4c1f-47a7-9455-62f53af36e3f.jpg)