There have been few victories for Google in the now 8-year-old lawsuit involving its massive Google Books digitization project. Google has now scanned and digitized over 20 million books. Google once reached a settlement with its major pursuer, the Authors Guild, only to have the settlement thrown out by a court. The court found even the compromise offered by its opponent too lenient. Therefore, it might be a bit surprising to find the same court giving Google a resounding victory in Google's latest battle with the Authors Guild. One never knows.

Over a decade ago, Google announced its project, now known as “Google Books,” to make digital copies of virtually every book, at least every older book ever published, available. It signed agreements with various university and public libraries to scan the older books on their shelves. Google agreed to pay the cost of scanning the books. The library and Google would each get a copy of the digital books created by the project.

There was an issue lurking behind this amazing project to preserve and make available older, often virtually “lost” books – copyrights. Copyrights on books published before 1923 have all expired. Google is free to copy them at will. Those published between 1923 and 1977 may, or may not still be under copyright, depending on whether copyrights were renewed years ago. Everything from 1977 on is still under copyright and will be for years to come.

While Google stayed away from newer books, it did scan many from the 1923-1977 period. It did not attempt to determine which were still under copyright and which were not. Even if it did, it would be essentially impossible to locate all of the copyright holders. That person may have died almost a century ago, and the copyright may now belong to dozens of impossible to find great-grandchildren, who aren't even aware that they own a copyright to a book that hasn't earned a nickel in 90 years. These books have earned the sobriquet “orphan books” in the trade. If Google had to seek the owners' approval first, as copyright law demands, it would be impossible for Google to make many books published after 1923 digitally available to the public.

Nonetheless, this was the issue over which the Authors Guild sued. You need the authors' permission first, no matter that doing so is essentially impossible, they said. That is what the letter of the copyright law says. So, Google and the Authors Guild reached a settlement. Google would sell digital access to books that might be under copyright. The copyright holder would get 63% of the proceeds, Google 37%. All the copyright holder had to do was step forward and claim their share. If they did not, their share would be held in abeyance for a few years and then donated to charity. Any copyright holder who did not like this deal could opt out and Google would immediately delete their books from its database.

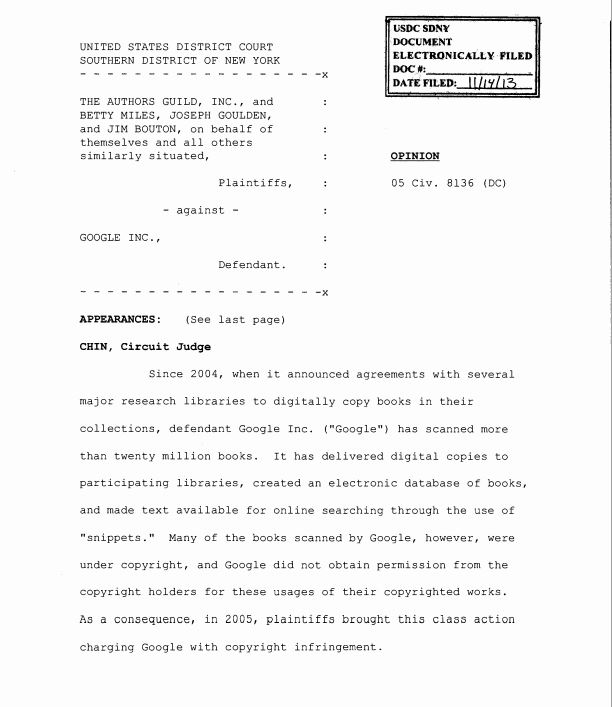

The settlement sounded reasonable enough, but others, including the U. S. Department of Justice, did not like the deal. It might be reasonable, they said, but it still violates the copyright law. The law is the law, and the law says you must receive permission to copy in advance, not after the fact. Ultimately, Judge Denny Chin of the District Court for the Southern District of New York agreed. You cannot reach a settlement that violates the law, he reasoned. He threw out the settlement, whereupon, the Authors Guild took up its suit against Google again.

This time, Google is no longer attempting to sell access to these “orphan books.” Instead, it allows Google searchers to see a short section, a “snippet” of text if it matches a visitor's search terms. This enables a searcher to find which books contain his search terms, and to see their context in a sentence or two. However, the person cannot then buy access to the book from Google. He is on his own. Google will point them to a book listing site if one has that book for sale, or to a library if it has the book on its shelves. You just can't get the book from Google, and Google does not receive advertising dollars from the book listing sites or from others on the page. It does not make any money from the copyrighted book.

The Authors Guild sued Google anyway. It is still copying and displaying parts of copyrighted books without the owners' permission. That is still a violation of copyright law, they argued. Google countered that what they were displaying represented what is legally known as “fair use” of copyrighted material. Without going into the details, or the official “four-pronged” test of fair use, an easy example of fair use is a book review. A reviewer can legally quote a couple of sentences from a book in her review. She just can't copy and quote the entire book. That is what Google said it was doing by displaying a “snippet.”

So, the suit was heard again in the same court in front of the same judge, but this time Judge Chin ruled in favor of Google. He concluded that Google's “snippets” constituted fair use. The Authors Guild pointed to the fact that Google, while only displaying a snippet, was, in fact, copying the entire book. And, if the searcher did enough searches using various terms, he could eventually see the entire book. Not so, said the Judge. First of all, Google leaves 10% of the copy out of its searches to prevent this. Secondly, in order to know what other terms to search to see the entire book, you would have to have a copy of the book in front of you. Accessing an entire book, or even the 90% available, is practically speaking, as likely as finding the copyright holders for books 90 years out of print. Google may continue to digitize books and display snippets to searchers on their website, ruled the Judge.

The Authors Guild is appealing. “In our view, such mass digitization and exploitation far exceeds the bounds of fair use defense,” Authors Guild Executive Director Paul Aiken said in a statement. “We plan to appeal the decision.”

We conclude with a quote from Judge Chin which puts this all in perspective, followed by a comment: “In my view, Google Books provides significant public benefits. It advances the progress of the arts and sciences, while maintaining respectful consideration for the rights of authors and other creative individuals, and without adversely impacting the rights of copyright holders. It has become an invaluable research tool that permits students, teachers, librarians, and others to more efficiently identify and locate books. It has given scholars the ability, for the first time, to conduct full-text searches of tens of millions of books. It preserves books, in particular out-of-print and old books that have been forgotten in the bowels of libraries, and it gives them new life. It facilitates access to books for print-disabled and remote or underserved populations. It generates new audiences and creates new sources of income for authors and publishers. Indeed, all society benefits.”

We agree completely with Judge Chin's summary, and yet, we can't help but note how much better the situation would have been had he ruled in favor of the earlier settlement. This decision allows people to locate potentially useful books online through Google, but to actually read it, they must order a copy online, likely through a site like Amazon or AbeBooks, providing one is even available, or find it in a library, the nearest one having their book perhaps hundreds or thousands of miles away. If the settlement had been upheld, they could have had instant access to a digital copy. And, as to generating “new sources of income for authors and publishers,” that will only be true of books still in print. Out of print books will be purchased used, meaning the author receives no further royalty, or read for free in a library. If Google were permitted to sell access, the author or publisher could have earned 63% of the selling price on the spot for a book they are otherwise unlikely to make another penny from ever again.

However, since the law is the law, the solution now is for Congress to change the copyright law to allow for a solution like the settlement to make “orphan books” accessible again. Congress just needs to get up off of their seats and do something useful, instead of whatever it is they are doing now.

![<b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633. <b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/8caddaea-4c1f-47a7-9455-62f53af36e3f.jpg)