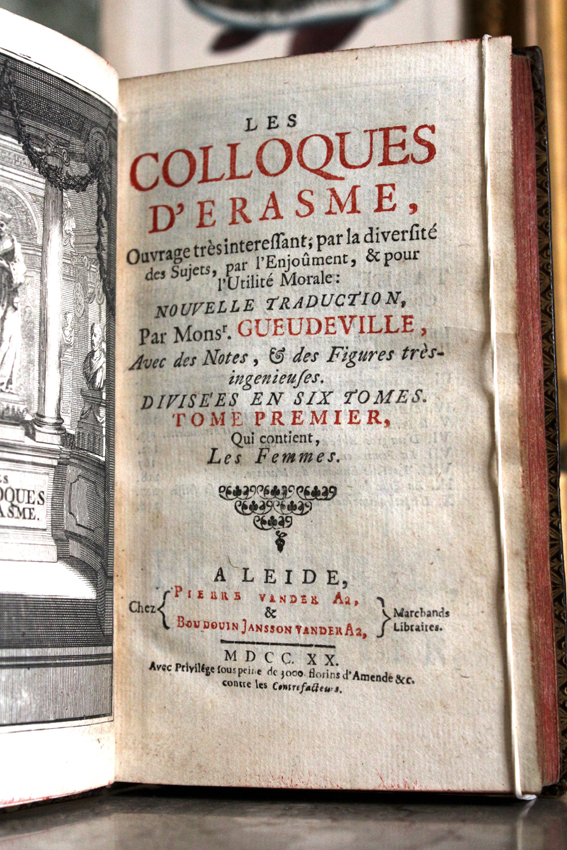

In Praise of Folly, by Desiderius Erasmus, is a masterpiece of the Renaissance. When I read it for the first time, I felt like I was infected by a virus, turning page after page, restlessly giggling. Folly had had the better of me. Erasmus was a moralist who feared not to explore the darkness of Man. “This book,” says his French translator Gueudeville in the Preface of the 1745 edition (Amsterdam), “is a declaration of war on Man.” Call me a masochist if you please, I decided to find more about Erasmus. I had heard about his Colloquies, but not reading Latin – poor me ! - I was to look for a French edition. I got a hold of the 1720 edition (Leide) and found out it had been translated from Latin by the same Nicolas Gueudeville.

Starting to read it, I tried to convince myself for a while that I had the fun of my life. Erasmus depicts different characters of his time through short dialogues... full of wit and irony? Some are indeed. But I soon had to admit that this book was not matching my expectations. I was puzzled by the lack of fierceness of the author and grew quite suspicious towards the numerous engravings that illustrate the text. “Without any historical consideration,” as I later read in the forewords of Develay’s translation, “the artist took the liberty to dress Erasmus’ characters with 18th century’s clothes.” So far from Holbein’s drawings joined to In Praise of Folly! In fact, it resembles a pale imitation, and that was no better omen to me. I started to wonder, what was the input of Gueudeville in this work? Had he respected the original, or tried to spread his own message using the name of a respected author, as he once did with Le Baron de Lahontan? In a word, was Gueudeville trying to fool me just because I can’t read Latin? Damn, this is something I was not ready to accept, even from a long time dead man.

Translation has become a sacred art. It was not so in the early days when publishers and translators would openly cut off the “weak parts” of any book, just to make it “easier to read”. It was no big deal, they proudly mentioned it in their forewords – it was even used as a marketing tool. That’s probably why I was so quick at suspecting Mr. Gueudeville. I had so far respected him for being involved in many interesting projects, including his translations of In Praise of Folly and Utopia by Thomas More. I knew he had also written an exciting follow-up to the Voyages du Baron de Lahontan dans l’Amérique Septentrionale (1703). Mr. Lahontan was sent to Canada in the late 17th century where he clearly got fascinated by the local “Savages”. Some accused him of speaking his own mind when he had an Indian saying about the death of Christ : “God, in order to please God, made God die.” This inspired Gueudeville, who decided to write an imaginary dialogue between the Baron and an Indian, entitled Dialogue de M. le Baron de Lahontan et d’un sauvage de l’Amérique (1728). It enabled him to freely criticize the Catholic doctrine but also to become a precursor of the “myth of the good Savage” (as opposed to the corrupt man living in society) that would later make Jean-Jacques Rousseau famous. It took some time before people realized it was a hoax. Leibtniz himself, as reported, thought Lahontan was the true author of this dialogue.

I started to read a few biographies of Gueudeville. Obviously, he was no recommendable man. He was born in Rouen, France, in 1652, and he started to study religion before entering the Congregation of Saint-Maur aged 17. Though a brilliant student, he had to run away from the wrath of his superiors after uttering some heretical theories – aaaah, here we are ! He soon became a Latin teacher in Rotterdam, Holland, where he turned Calvinist. He eventually settled in Leyde where he started to earn a living by writing and translating books. Mr. Gueudeville was clearly not a wealthy man, the Dictionary of Mr. Feller even states that he “died out of misery.” To Mr. Feller, Gueudeville was just an up-to-no-good so-called writer, who had given “lengthy and dull” translations of In Praise of Folly and of Utopia (More). His style, he writes, “was emphatic, low, full of vulgar expressions, obscene – in a word, perfectly fitting the rabble.” It is true that Mr. Gueudeville was not afraid to use derogatory words such as “merdard”, and that Mr. Fauche, in his 1777 edition (Neuchatel) of In Praise of Folly, confessed that the original translation of Gueudeville was a little bit rude, and that he had tried to correct it as much as possible. Nevertheless, Mr. Feller was an Abbot, deeply and stubbornly opposed to Voltaire and the philosophers of his time. I guess it was a compliment to be insulted by such a man. But even Chaudon & Delandine despised Gueudeville in their Historical Dictionary – in fact, Feller’s article is almost stolen word for word from Chaudon’s (and this man was giving lessons of morality). As far as Gueudeville’s translation of Plaute’s Comedies is concerned, Chaudon writes: “The text is drowned under a flow of pestilence.” The man himself? “A villain, who, being tired of drinking wine, spent the last years of his life drinking strong liquor.” Jump from the frying pan and end up in the fire!

I’ve also learnt to be suspicious towards the established writers of the 18th century (including those who wrote dictionaries). They were experts in the art of flattering and usually chose their targets, sparing the powerful while harassing the weak. Gueudeville was guilty of being, first of all, a Protestant. Worst than that, a former Catholic who had betrayed his faith and his King – and not any King, but the great Louis XIV. He published, from 1699 onwards, the famous Esprit des Cours de l’Europe, a periodical Gazette. Chaudon laughs: “It was written by a man who had never seen the Cabinet of a Minister.” He knew enough to upset le Comte d’Avaux, anyway, who “had the publication suppressed because France was often offended by it.” (Chaudon).

![<b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 16:</b> [Austen, Jane]. A handsome first edition of <i>Sense and Sensibility,</i> the author's first novel. $60,000 to $80,000. <b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 16:</b> [Austen, Jane]. A handsome first edition of <i>Sense and Sensibility,</i> the author's first novel. $60,000 to $80,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/9a74d9ff-42dd-46a1-8bb2-b636c4cec796.png)

![<b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633. <b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/8caddaea-4c1f-47a7-9455-62f53af36e3f.jpg)