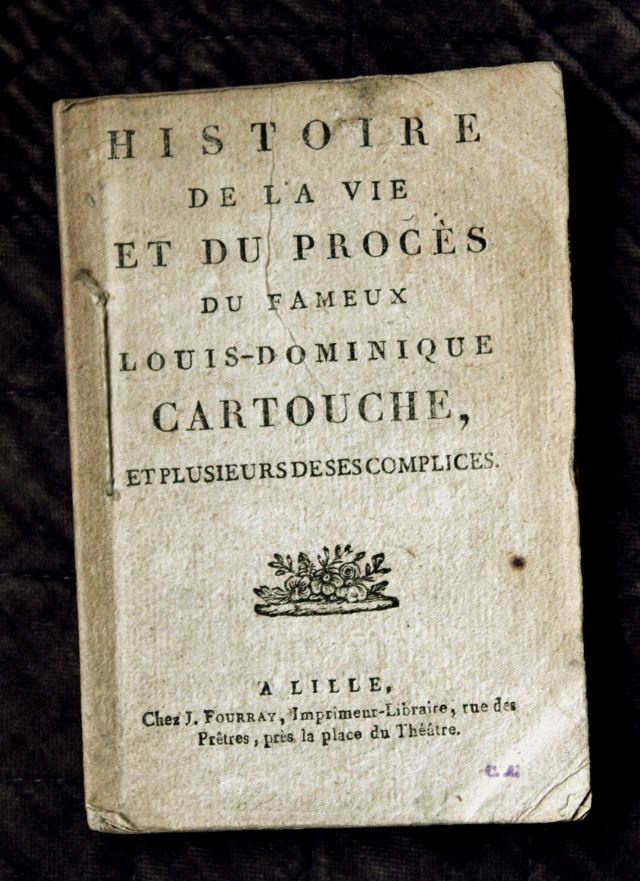

The other day, passing in front of a bookshop in Paris, I noticed a lovely little book in the window. Beside a lot of gorgeous full morocco bindings, it never looked that attractive, being a small and thin in-18 volume from the 19th century, unbound as issued (the 72 pages being bound together with a mere length of string), printed on a low quality paper and with no wrappers. The title read, in French : History of the Life and Trial of the Notorious Louis-Dominique Cartouche, and of Several of his Accomplices... printed in Lille, in the North of France, by one J. Fourray. This is one of the most famous titles of the editions of “colportage” or peddling books, retracing the career of a French bandit who terrorized the country until being executed in 1721. Regarded as a “Robin Hood” by some, allegedly linked to a lot of powerful people of his time, Cartouche stands amongst the most romantic villains of France. As a child, I used to watch his exploits in a movie featuring the irresistible Claudia – Ô Claudia! - Cardinal. I entered the shop.

Diogenese the Cynic claimed to live happy in poverty. Socrates came to him one day: “I see vanity through the holes of your coat.” I see almost the same thing in a religious book bound in an expensive binding... God deserves the best, I guess. Anyway, that’s what is so exceptional about this particular book, it has the look of what it talks about. This is the book of raw life, adventure and badness. In both senses of the term, this is a popular book. “Louis-Dominique Cartouche was born in Paris in 1693," reads the book, "in the quarter of La Courtille.” Sent to the Jesuits, the little boy started to rob to buy clothes that could match those of his wealthy school mates. One evil leading to another, he eventually had to run away from the wrath of the law a few years later. He was then sheltered by a bunch of Bohemians who taught him all the tricks in the game.

Back to Paris he became an informer and a recruiter for the army, then a soldier against his will. The peace of Utrecht sent him back to idleness. “As a cunning, skilful and robust man," reads the dictionary of F.X. de Feller (Liege, 1793), "he soon took the lead of a bunch of robbers who illustrated themselves by numerous robberies and murders.” In fact, Cartouche motivated some of his former soldier friends, and set up a confederacy of 200 men (by the end of his career, he was said to control over 2,000 men). “He dedicated himself to teach his subjects by hardening their spirits," continues the book; "he taught their hands to steal and their hearts to murder. Soon after, you heard nothing in Paris but stories of people being robbed, thrown into the river, and murdered on the Pont-Neuf.” The book also mentions a few tricks Cartouche allegedly invented, including the wax hand that pretended to pray at church while the real one was digging into the pocket of the nearest penitent. A technique I thought for years was invented by Benny Hill for his English TV comedy show but which was in practice since the 17th century.

“The public became incredible fond of Cartouche," say the forewords. "Had a Gazette nothing else to say but that Cartouche was nowhere to be found, people would be glad to read it.” Such was the craze over this dark man. Cartouche loved robbing the rich. He would attack the stagecoach between Paris and Versailles, where the Court was residing, and loot some private mansions, thus earning the reputation of a Robin Hood in a very corrupted time. He became powerful once paper money was established, as “the simple wallet he robbed with his friends put them at their ease.” He went to a banker one day, very well dressed, gave him 4,000 gold louis and obtained a “lettre de change” (the ancestor of cheques) that, he said, he would cash in Lyon where he was expected. One of his accomplices left for Lyon at once with a counterfeit letter while Cartouche went back to the banker the next day, claiming that his journey had been postponed and thus got his money back at the same time his villain friend was being paid in Lyon.

![<b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 11:</b> Darwin and Wallace. On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties..., [in:] <i>Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnean Society,</i> Vol. III, No. 9., 1858, Darwin announces the theory of natural selection. £100,000 to £150,000. <b>Sotheby’s, Dec. 11:</b> Darwin and Wallace. On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties..., [in:] <i>Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnean Society,</i> Vol. III, No. 9., 1858, Darwin announces the theory of natural selection. £100,000 to £150,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/00d5fd41-2542-4a80-b119-4886d4b9925f.png)