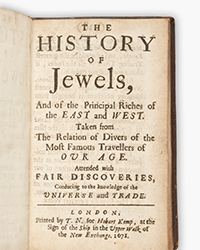

Eight years ago, a request to see an old map of the Mississippi River from a patron at the Royal Library of Sweden led to the unraveling of one of the greatest book and map thefts of recent memory. The map wasn't there. So weren't a lot of other books. It set off an internal investigation, with evidence pointing to an inside job. It would not be long before the head of the Royal Library's manuscript department, Anders Burius, confessed. He had taken 56 old and valuable books from the library between the time he was hired in 1995, and what was then the present, 2004. Evidence discovered at his home indicated he had been stealing books from other sources for ten years prior to his appointment to the Royal Library.

Burius' modus operandi was to take the books and scratch off the library markings. He would remove cards from the card catalogue so that no one would miss the books. He then took them to the auction house of Ketterer Kunst and its predecessor to be put up for sale. Fellow librarians were surprised by such things as Burius' expensive clothes on a library salary, but no one really knows how much money others have from legitimate sources, so no undue suspicions were aroused.

Burius did not stick around long enough to face the music. On a temporary release from custody while awaiting a court hearing, Burius went to his apartment, slit his wrists, and severed a gas main. Eventually, a spark set off the escaping gas, resulting in a major explosion. The walls of his apartment were demolished, with debris scattered everywhere. Around a dozen people were injured, many more were forced from their homes. Burius died.

That seemed to be the end of the story. The Swedish government issued a report about the case in 2008, and a documentary was broadcast over Swedish radio in 2009, but essentially, the case was forgotten. However, one element remained missing – the books. None of the 56 books stolen from the Royal Library were ever recovered. Why this fact seems to have been placed on the back-burner is unclear, since Burius had told officials where he had taken them, but perhaps everyone concluded it was too difficult to pursue them further. This part is hard to understand.

Finally, last summer, a member of the library staff noticed a copy of the rare Wytfliets Atlas, one of the 56 stolen books, posted for sale at Arader Galleries in New York. The Swedish Library contacted the Arader Galleries with their suspicions. The Arader Galleries requested photographs of the Royal Library's copy, and after comparing them with the copy in their possession, realized what they had was the library's stolen copy. The firm's owner, Graham Arader, had purchased it at a Sotheby's auction on May 7, 2003, for $100,000.

Mr. Arader was mystified as to why the Royal Library had not posted a list of missing items long ago. That is another aspect of this case that is hard to explain. Sometimes, libraries can be embarrassed by having their items stolen. It may make them look lax. Whatever the reason, Mr. Arader, who is noted in the field as a hawk about tracking down map thieves, was unaware that he had a stolen atlas in his possession. Indeed, for years he had openly advertised it on his website with no one notifying him that it might be a stolen copy until eight years later.

Once ownership was established, the Arader Galleries quickly returned the book to Sotheby's. They held it, performing whatever due diligence was necessary, and presumably attempting to track down the book's history, returning the book to the Royal Library this June 27 past. Sotheby's reimbursed Mr. Arader his purchase price. It has not been released whether Sotheby's has been reimbursed its losses by anyone else in the chain of possession. Presumably, someone is out a substantial sum of money, as it is unlikely there is much if anything left of what Burius obtained. It should be noted that there are still 55 more such books out there, so there is still a substantial amount of losses to be realized if the Swedish library continues to locate more of its missing books.

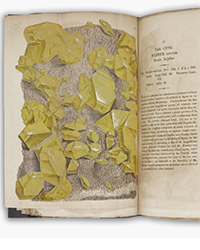

Map Librarian Greger Bergvall described the Wytfliets Atlas as the first atlas devoted exclusively to maps of North and South America, and the first to include a printed map of California. The atlas was published in 1597. National Librarian Gunilla Herdenberg added, “We could not be more thrilled that this national treasure has finally been returned.” The Royal Library, along with legal representatives it has hired, and government agencies on both sides of the Atlantic, plan to pursue the remaining 55 volumes aggressively now. A list of the missing books has been published and can be found at the following link: wytflietatlas.

![<b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633. <b>Heritage, Dec. 15:</b> John Donne. <i>Poems, By J. D. With Elegies on the Author's Death.</i> London: M[iles]. F[lesher]. for John Marriot, 1633.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/8caddaea-4c1f-47a7-9455-62f53af36e3f.jpg)