-

Sotheby’s

New York Book Week

12-26 JuneSotheby’s, June 25: Theocritus. Theocriti Eclogae triginta, Venice, Aldo Manuzio, February 1495/1496. 220,000 - 280,000 USDSotheby’s, June 26: Fitzgerald, F. Scott. The Great Gatsby, 1925. 40,000 - 60,000 USDSotheby’s, June 26: Blake, William. Songs of Innocence and of Experience, Printed ca. 1381-1832. 400,000 - 600,000 USDSotheby’s, June 26: Lincoln, Abraham. Thirteenth Amendment, signed by Abraham Lincoln. 8,000,000 - 12,000,000 USDSotheby’s, June 26: Galieli, Galileo. First Edition of the Foundation of Modern Astronomy, 1610. 300,000 - 400,000 USD -

Finarte

Books, Autographs & Prints

June 24 & 25, 2025Finarte, June 24-25: ALIGHIERI, DANTE / LANDINO, CRISTOFORO. Comento di Christophoro Landino Fiorentino sopra la Comedia di Danthe Alighieri poeta fiorentino, 1481. €40,000 to €50,000.Finarte, June 24-25: ALIGHIERI, DANTE. La Commedia [Commento di Christophorus Landinus]. Aggiunta: Marsilius Ficinus, Ad Dantem gratulatio [in latino e Italiano], 1487. €40,000 to €60,000.Finarte, June 24-25: ALIGHIERI, DANTE. Il Convivio, 1490. €20,000 to €25,000.Finarte

Books, Autographs & Prints

June 24 & 25, 2025Finarte, June 24-25: BANDELLO, MATTEO. La prima [-quarta] parte de le nouelle del Bandello, 1554. €7,000 to €9,000.Finarte, June 24-25: LEGATURA – PLUTARCO. Le vies des hommes illustres, grecs et romaines translates, 1567. €10,000 to €12,000.Finarte, June 24-25: TOLOMEO, CLAUDIO. Ptolemeo La Geografia di Claudio Ptolemeo Alessandrino, Con alcuni comenti…, 1548. €4,000 to €6,000.Finarte

Books, Autographs & Prints

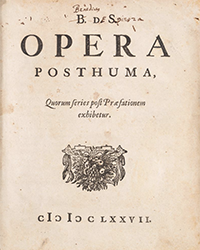

June 24 & 25, 2025Finarte, June 24-25: FESTE - COPPOLA, GIOVANNI CARLO. Le nozze degli Dei, favola [...] rappresentata in musica in Firenze…, 1637. €6,000 to €8,000.Finarte, June 24-25: SPINOZA, BARUCH. Opera posthuma, 1677. €8,000 to €12,000.Finarte, June 24-25: PUSHKIN, ALEXANDER. Borus Godunov, 1831. €30,000 to €50,000.Finarte

Books, Autographs & Prints

June 24 & 25, 2025Finarte, June 24-25: LIBRO D'ARTISTA - LECUIRE, PIERRE. Ballets-minute, 1954. €35,000 to €40,000.Finarte, June 24-25: LIBRO D'ARTISTA - MAJAKOVSKIJ, VLADIMIR / LISSITZKY, LAZAR MARKOVICH. Dlia Golosa, 1923. €7,000 to €10,000.Finarte, June 24-25: LIBRO D'ARTISTA - MATISSE, HENRI / MONTHERLANT, HENRY DE. Pasiphaé. Chant de Minos., 1944. €22,000 to €24,000. -

Bonhams, June 16-25: 15th-CENTURY TREATISE ON SYPHILIS. GRÜNPECK. 1496. $20,000 - $30,000Bonhams, June 16-25: THE NORMAN COPY OF BENIVIENI'S TREATISE ON PATHOLOGY. 1507. $12,000 - $18,000Bonhams, June 16-25: FRACASTORO. Syphilis sive Morbus Gallicus. 1530. $8,000 - $12,000Bonhams, June 16-25: THE FIRST PUBLISHED WORK ON SKIN DISEASES. MERCURIALIS. De morbis cutaneis... 1572. $10,000 - $15,000Bonhams, June 16-25: BIDLOO. Anatomia humani corporis... 1685. $6,000 - $9,000Bonhams, June 16-25: THE NORMAN COPY OF DOUGLASS'S EARLY AMERICAN WORK ON INNOCULATION AND SMALLPOX. 1722. $20,000 - $30,000Bonhams, June 16-25: LIND'S FIRST TREATISE ON SCURVY. 1753. $15,000 - $20,000Bonhams, June 16-25: RARE JENNER SIGNED CIRCULAR ON VACCINATION. 1821. $4,000 - $6,000Bonhams, June 16-25: MOST BEAUTIFUL OF MEDICAL ILLUSTRATIONS. BRIGHT. Reports of Medical Cases... 1827-1831. $10,000 - $15,000Bonhams, June 16-25: FLORENCE NIGHTINGALE PRESENTATION COPY TO HER MOTHER. 1860. $6,000 - $8,000Bonhams, June 16-25: LORENZO TRAVER'S MANUSCRIPT JOURNAL OF BURNSIDE'S NORTH CAROLINA EXPEDITION. TRAVER, Lorenzo. $2,000 - $3,000Bonhams, June 16-25: ONE OF THE EARLIEST PHOTOGRAPHIC BOOKS ON DERMATOLOGY. HARDY. Clinique Photographique... 1868. $3,000 - $5,000

-

Dominic Winter Auctioneers

June 18 & 19

Printed Books & Maps, Children's & Illustrated Books, Modern First EditionsDominic Winter, June 18-19: World. Van Geelkercken (N.), Orbis Terrarum Descriptio Duobis..., circa 1618. £4,000-6,000.Dominic Winter, June 18-19: Moll (Herman). A New Exact Map of the Dominions of the King of Great Britain..., circa 1715. £2,000-3,000.Dominic Winter, June 18-19: Churchill (Winston S.). The World Crisis, 5 volumes bound in 6, 1st edition, 1923-31. £1,000-1,500Dominic Winter Auctioneers

June 18 & 19

Printed Books & Maps, Children's & Illustrated Books, Modern First EditionsDominic Winter, June 18-19: Darwin (Charles). On the Origin of Species, 2nd edition, 2nd issue, 1860. £1,500-2,000.Dominic Winter, June 18-19: Roberts (David). The Holy Land, 6 volumes in 3, 1st quarto ed, 1855-56. £1,500-2,000.Dominic Winter, June 18-19: Saint-Exupéry (Antoine de, 1900-1944). Pilote de guerre (Flight to Arras), 1942. £10,000-15,000.Dominic Winter Auctioneers

June 18 & 19

Printed Books & Maps, Children's & Illustrated Books, Modern First EditionsDominic Winter, June 18-19: Austen (Jane, 1775-1817). Signature, cut from a letter, no date. £7,000-10,000Dominic Winter, June 18-19: Huxley (Aldous). Brave New World, 1st edition, with wraparound band, 1932. £4,000-6,000Dominic Winter, June 18-19: Tolkien (J. R. R.) The Hobbit, 1st edition, 2nd impression, 1937. £3,000-5,000Dominic Winter Auctioneers

June 18 & 19

Printed Books & Maps, Children's & Illustrated Books, Modern First EditionsDominic Winter, June 18-19: Rackham (Arthur, 1867-1939). Princess by the Sea (from Irish Fairy Tales), circa 1920. £4,000-6,000Dominic Winter, June 18-19: Kelmscott Press. The Story of the Glittering Plain, Walter Crane's copy, 1894. £3,000-4,000Dominic Winter, June 18-19: King (Jessie Marion, 1875-1949). The Summer House, watercolour. £4,000-6,000

Rare Book Monthly

Articles - October - 2010 Issue

The Collector Becomes a Seller

For this, my second auction, I've consigned to Bonham's who have been studying my American collection for months and preparing descriptions and images for inclusion in a hard-bound catalogue due to be released in late October. Just as a lawyer who defends himself has a fool for a client I long ago recognized that the organizing of a collection to sell requires intelligent, dispassionate perspective and description that are best provided by they who sell rather than they who own. To ensure impartiality I have, from the outset, ceded control of estimates to the house. I have asked only that the what, when, and from whom purchased details are included in the descriptions. In selling material I have valued I do not seek confirmation that I bought well or wisely. I'll return it to the market in the same spirit I acquired it - with great interest but no specific expectation. I understand the estimates will be consistently below what I paid ten to twenty years ago. The auction would not be interesting otherwise.

I am of course hopeful of a good outcome but if there is one, it will be overall. Some items will sell for a song while others do well. In either case the market will render a decision. I will not intrude with reserves that protect the lots from rejection. The material is extremely good, often exemplary, more than half purchased from or through the William Reese Company.

Now as I write this piece the collection is in the hands of Christina Geiger, Director of Books and Manuscripts in New York and two cataloguers, Adam Stackhouse and Matthew Haley, who together are creating a coherent narrative and telling the story of an emerging continent, whose boundaries and salient characteristics are, as the collection begins in 1630, yet to be fully described. In the collection what was then known is described in the different languages of the explorers as their backers and investors angle for control. The Dutch, English, Spanish and French all seeking, from great remove, to control by words what they barely comprehend, a geography two and a half times as large as Europe, itself still an incomplete idea. These early books both convey the story and suggest the posting of flags, the "hey we're here" implications that buttress aspirations and claims, the "we don't know what we have but we have it" perspective.

In the progression of the material, always in date order, the British become established in America, the French in Canada and the Spanish in Mexico. Development and control then becomes chess on a grand scale. For the home countries it is a losing game although it will take time to play out. Ultimately the increasingly ungrateful explorers, settlers and pioneers of America become its proprietors and demand independence, an outcome as inevitable as the timing is uncertain. Such large places are ungovernable without consent of the governed. We know this today. In breaking away, the Americans strike first, next the Canadians and then the Mexicans; the absence of cooperation and the leeway to govern locally mostly determining the inevitable divorces.

With the coming of the 19th century, industrial development, the spread of literacy and the suppression of fatal illness together make it possible for the landless indigent to reach American shores and find, in its vastness, a place to settle and prosper. This leads to the final portion of this collection, the western advance.

Through the century accounts, explanations, perspectives, maps and illustrations are transformed. Some books tell us of discovery. Others confirm common knowledge. More information is needed; more is gathered, and more distributed. Literacy, the lucky possession of a few at the turn of the century becomes the widely held essential skill of an America moving from farm to factory, from country to city. In the explosion of literacy, in the proliferation of printed material, we see the confirmation that more people can read and that they want to read more.

![<b>Finarte, June 24-25:</b> ALIGHIERI, DANTE. <i>La Commedia [Commento di Christophorus Landinus]. Aggiunta: Marsilius Ficinus, Ad Dantem gratulatio [in latino e Italiano],</i> 1487. €40,000 to €60,000. Finarte, June 24-25: ALIGHIERI, DANTE. La Commedia [Commento di Christophorus Landinus]. Aggiunta: Marsilius Ficinus, Ad Dantem gratulatio [in latino e Italiano], 1487. €40,000 to €60,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/4ee20109-25f3-42e8-93ab-bd4c8e17093a.png)

![<b>Finarte, June 24-25:</b> BANDELLO, MATTEO. <i>La prima [-quarta] parte de le nouelle del Bandello,</i> 1554. €7,000 to €9,000. Finarte, June 24-25: BANDELLO, MATTEO. La prima [-quarta] parte de le nouelle del Bandello, 1554. €7,000 to €9,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/5adfdf34-8a9a-47e5-9288-5e65dac5ce79.png)

![<b>Finarte, June 24-25:</b> FESTE - COPPOLA, GIOVANNI CARLO. <i>Le nozze degli Dei, favola [...] rappresentata in musica in Firenze…,</i> 1637. €6,000 to €8,000. Finarte, June 24-25: FESTE - COPPOLA, GIOVANNI CARLO. Le nozze degli Dei, favola [...] rappresentata in musica in Firenze…, 1637. €6,000 to €8,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/9a1b8605-a566-4fb7-8a4c-5fb72ac539bc.png)

![<b>Forum, June 19:</b> Euclid. <i>The Elements of Geometrie,</i> first edition in English of the first complete translation, [1570]. £20,000 to £30,000. Forum, June 19: Euclid. The Elements of Geometrie, first edition in English of the first complete translation, [1570]. £20,000 to £30,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/dbc5286a-4210-44e3-bbf0-6031c1c49801.png)

![<b>Forum, June 19:</b> Shakespeare (William). <i>The Tempest</i> [&] <i>The Two Gentlemen of Verona,</i> from the <i>Second Folio,</i> [Printed by Thomas Cotes], 1632. £4,000 to £6,000. Forum, June 19: Shakespeare (William). The Tempest [&] The Two Gentlemen of Verona, from the Second Folio, [Printed by Thomas Cotes], 1632. £4,000 to £6,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/655b361c-71c7-48ba-9455-09c14e8c7494.png)