Medical and Scientific History from James Tait Goodrich Antiquarian Books and Manuscripts

- by Michael Stillman

Medical and Scientific History from James Tait Goodrich Antiquarian Books and Manuscripts

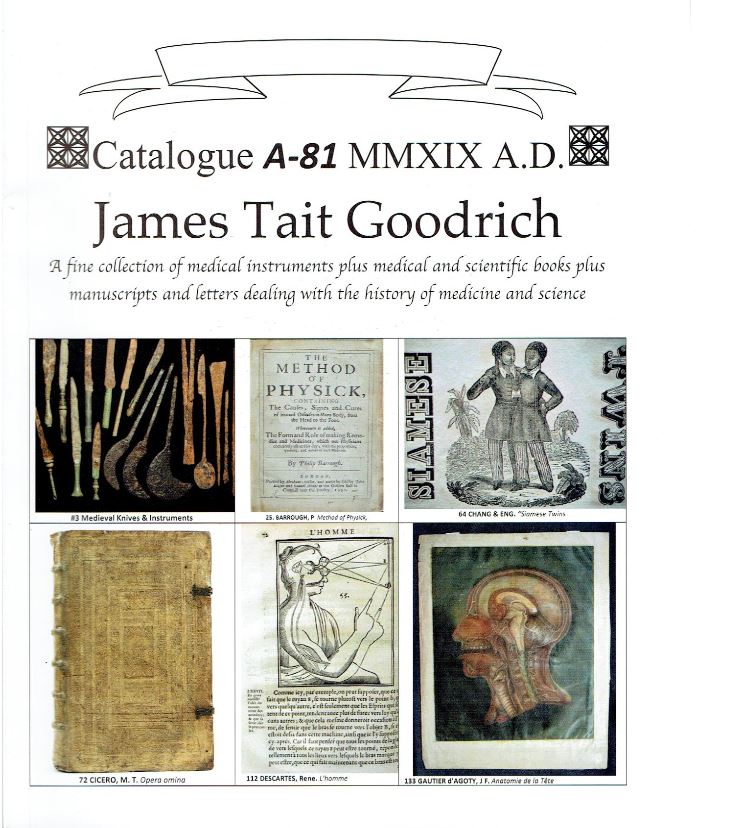

James Tait Goodrich Antiquarian Books and Manuscripts has issued their Winter 2019 Catalogue A-81, History of Medicine and Science, Pre-Columbian Artifacts, Medical Instruments and Antiques. While that covers several types of material and subjects, the great majority of what is offered are books, magazines, offprints and other paper related to the history of medicine. There is much in the way of early medical discoveries, and views of how it was practiced centuries ago. There are also a few very old surgical tools available that will make you thankful you did not live back them. Here are a few samples from this latest Goodrich catalogue.

We will begin with one of the most important figures in the history of medicine, though his discovery which has saved millions of lives came about quite by accident. He was not a notable researcher or scientist in 1929 when he was working in his lab. Alexander Fleming was simply trying to find some better antiseptics. Therefore, he had some petri dishes with bacterial cultures in them. One day, he left a window open and some outside air got into one of his cultures. Fleming noticed that all of the bacteria in one section of his petri dish died. He began looking for the cause and discovered it was a mold growing in the dish. Fleming had discovered penicillin, the first antibiotic. In 1929, the discovery did not have much practical effect. Penicillin could not be produced in sufficient quantities to be of use. However, when the war came around a decade later, governments threw their full resources into figuring out how to produce the drug in large quantities as it could save the lives of many thousands of injured soldiers. The problem was solved, and antibiotics have become essential in the practice of medicine ever since, saving countless lives everyday. Item 128 is a letter from Fleming to a Mr. Derwent dated April 11, 1945 (the year he won the Noble Prize). By then, volume manufacturing had been achieved and large quantities of the drug would soon be available to the public. Evidently, Mr. Derwent was hopeful that penicillin would be beneficial in treating arthritis. Fleming was doubtful. He writes, “In reply to your letter, we have tried penicillin on a few cases of arthritis with very little success and we have not pursued it as we thought it unjustifiable until the supply becomes ample. It will not be very long, however, before there is plenty of penicillin and then you will be able to try it but the chances are it will not be successful.” Priced at $9,000.

Next we have an account of a bizarre case that led to some of the most important discoveries concerning digestion. The title is Experiments and Observations on the Gastric Juice, and the Physiology of Digestion, and it was published in 1833 in the small, far northern New York town of Plattsburgh. The author was William Beaumont, an army physician on the frontier in the Michigan Territory. It was there that a French-Canadian woodsman named Alexis St. Martin walked in with a serious accidental gunshot wound to the stomach. He was in bad shape, but Beaumont was able to save him. The doctor fashioned a skin flap to cover the bullet hole, but then made an unusual request of his patient. Would he permit the physician to use the flap to gain access to and observe the actions of his stomach? Since St. Martin was in no shape to go back to the woods, he consented and became Beaumont's assistant. For the next ten years, Beaumont observed what was going on in St. Martin's stomach, at times putting food inside on a string, then pulling it out to see the effects of the gastric juices. Among Beaumont's discoveries was that emotions could effect the gastric juices, a precursor to Pavlov's findings with his dogs. Eventually, St. Martin did return to the woods, and lived a long life, either to his late 70s or 80s. Item 34. $2,000.

This is not at all typical of what is found in this catalogue, but there is a reason. Item 64 is an advertising broadside for Siamese Twins For ___ Day only United Brothers, Chang-Eng. This was for a show displaying the twins joined at the chest. The place and date are not filled in, but they toured during the 1830s. The twins were discovered by a merchant in Siam in 1829, hence the name “Siamese Twins” for conjoined twins. They were taken to America and made a decent amount of money appearing for display over the next decade. The price of admittance was 50 cents, which was a lot of cash in the 1830s, indicating how popular a draw they were. However, the brothers were not freak show types, and after putting away some money, bought a farm, married sisters, and had 21 children between them. Chang suffered a stroke in 1870, while Eng remained healthy through life. Chang died on January 17, 1974, and Eng followed him two hours later. $2,500

This leads us to the medical texts. Item 62 is An Account of the Siamese Twins United Together from Birth, in The American Journal of Medicine, volume 5, 1829. The account was written by Harvard Medical School professor John Collins Warren, who performed a thorough physical exam after the twins arrival in America that year at the age of 17. Warren felt it would be valuable to learn about whether their circulatory system would transfer medicines and disease between the two. He also posed “Another question which has presented itself in relation to them, is, whether it would be possible to separate them from each other safely.” Warren is noted as the first physician to perform surgery on a patient under ether anesthesia, which he accomplished in 1846. $750.

This next item also relates to Chang and Eng, but comes at the other end of their lives. The author of this report, published in 1875, the year after the twins died, was Dr. William H. Pancoast of Philadelphia. Pancoast answered the question Warren posed earlier in a report of the Surgical Considerations in Regard to the Propriety of an Operation for the Separation of Eng and Chang Bunker, Commonly Known as the Siamese Twins, in Transactions of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Philadelphia. Pancoast came to the conclusion that the band which connected them could only have been safely cut during their childhood. Item 63. $750.

Now we have a couple of those medical sets you can be thankful will never be used on you. Item 1 is a traveling amputation set produced in Germany circa 1790s. As the note about Dr. Warren performing the first surgery under anesthesia in 1846 attests, there was no anesthesia beyond maybe a stiff drink of whiskey that accompanied these amputations. The set, held in a leather covered wooden box, features an amputation saw and several other tools, including a bullet extractor. There is some rusting to the blades, so you will want to get a tetanus shot first if you choose to use them. This is a traveling set, meaning it probably was not being used in hospitals, but more likely in a doctor's office or the patient's home. $1,295.

Here is an even less useful medical set from the early 19th century. Item 2 is a bleeding and cupping set, held in a leather bound travel box. It contains two glass cups of different sizes and a brass scarificator. If you are unfamiliar with the term “scarificator,” it is probably because your doctor doesn't have one. If he does, stay away. It is a device with several spring-loaded blades that would instantly deliver several lacerations to your body. The cups would then be used to collect the bad blood that was being bled from your body. Of course, your better physicians no longer employ this practice. It had been used for many centuries, the theory being to remove bad spirits or whatever in your body that was making you ill. However, by the middle of the 19th century, most physicians realized the procedure was useless and could weaken the patient from blood loss, making it counterproductive to curing illness. $500.

James Tait Goodrich Antiquarian Books and Manuscripts may be reached at 845-359-0242 or James.Goodrich@Einstein.yu.edu.