African Americana from Langdon Manor Books

- by Michael Stillman

African Americana from Langdon Manor Books

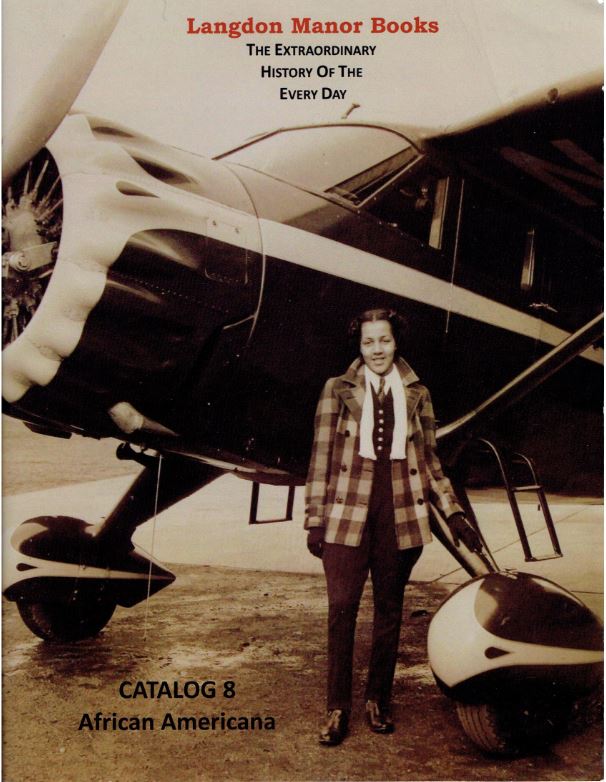

Langdon Manor Books has released their Catalog 8: African Americana. This collection contains much of the sort of material one would expect when it comes to the experiences of African Americans. Unfortunately, so much of that revolves around discrimination, from limited opportunities and segregation all the way to lynchings. There are many items related to the struggle for human rights, as well as living within the system imposed on them during the past century. Many are accounts of black American soldiers, people expressing their patriotism and love for America while facing the reality that not all of our rights were shared by them.

Also to be found in this collection are personal archives containing scrapbooks, letters, personal documents and photographs. These are the collections of regular people, living normal lives within the boundaries of segregation. It's hard not to wonder what became of these families, how personal memories collected over the years ended up with no family to speak for them anymore. The families drifted away, dispersed by time. Time changes us all, regardless of race. Here are a few selections from this catalogue.

Auto travel has been one of America's favorite pastimes since the invention of the automobile and the building of roads to accommodate them. However, it was not so easy for all. Whites could hop in their car, stay at any motel, eat at any restaurant, visit any establishment along the way. It was not so for African Americans. In the South, it could be dangerous, some towns outlawing blacks on the street after dark, the threat of the KKK and similar types of people always present. Even in parts of the country not quite so dangerous, discrimination was legal and widespread and the sheer embarrassment of being turned away was always there. It led to several publications that found out which establishments would welcome black guests so African American travelers would know where they could stop. The best known of them is the "Green Book," published from the 1930s to the 1960s. Here is one less well-known, Go Guide to Pleasant Motoring. It began in 1952 with the purpose "to save Negroes embarrassment and trouble on their vacations." It listed only establishments that "welcome all guests regardless of race, religion or nationality." Along with local advertising, it carried promotions for Amoco and Phillips Petroleum, and the travel accoutrement, Coca-Cola. Item 6 is a 1964 edition. The Go Guide, like the "Green Book," closed down in the 1960s after the passage of the Civil Right Act made discrimination in public accommodations illegal. Priced at $3,250.

Black Americans did have one power they could wield at times, the power of the purse. They were consumers, too, and some businesses, though white owned, largely catered to black audiences. Item 10 is a handbill published by the Negro Labor Relations League of Chicago in 1959-1960. This one called for a boycott of products from the Agar Packing Co. They produced various pork products that were widely sold in African American neighborhoods. The handbill tells readers, "Don't Buy Agar Products. Don't Buy Agar Chitterlings." Why? The heading explains, Agar Waxes Fat, Loud and Wrong. More specifically, "Agar Packing Co. Refuse to Hire Negro Women." An illustration depicts a humanized Agar meat tin telling a black woman, "We'll take your money...but we don't need you!" The boycott began in 1959, and the company reported average weekly losses of $44,000. They gave in in 1960, hiring black as well as white women to work in their plant. Item 10. $450.

Since the passage of the 14th Amendment after the Civil War, white politicians have often sought the black vote, realizing it could be crucial in a close election. They rarely gave much in return, a bone here and there, perhaps a few nice words with little behind them. African American voters had to figure which one might do a little for them, or at least, be less harmful. Republicans had a natural advantage for years, being the party of Lincoln, but the party differences on race relations tended not to be that much, more dependent on local factors than national beliefs or strategies. In 1912, the presidential election was a three-way race. Former President Theodore Roosevelt had made some early overtures toward more equal rights, but largely abandoned them in response to white hostility. His successor, Republican William Howard Taft, didn't do much either. Democratic nominee Woodrow Wilson stirred some hope, but ultimately proved, if anything, more unfriendly than the other two. Item 49 is a handbill published by the Republican National Committee Woman's Department headed, Afro-Americans Stop! Read! Think! It's primary arguments are historical, reminding black voters of Abraham Lincoln and the freeing of slaves, then almost 50 years in the past. It does claim Taft's sympathy for their cause and having provided some jobs. The notice is attributed to Helen Varick Boswell. Ms. Boswell was a white woman who promoted equal rights, but those were primarily equal rights for women, not African Americans. She had been appointed in 1907 by then Secretary of War Taft to go to the Panama Canal Zone to set up women's organizations for the benefit of the wives of canal workers. The situation had become stressful for them with little to do. However, Ms. Boswell's main cause was the Republican Party, and for 50 years she loyally promoted the interests of the party regardless of who was their nominee. Item 49. $400.

Item 27 is a notebook kept by a young African American student from the mid-1890s - 1902. It would have covered his teenage years to early 20s. His name was Walter Alexander and he lived in Ironton, Ohio. It contains 124 handwritten pages, including school work for chemistry, music and government. There is a three-page Latin translation. Of greater interest are some essays he wrote, which express the frustration of people working to better themselves and contribute to society, but still being treated poorly. He advocates more independence, patronizing fellow African Americans in business and other endeavors. He makes an observation which could still be made today with regard to too many whites: "White people do not measure the good deeds done by the negro, but instead they ferret out the very worst things and by the bad deeds they measure the entire race. Isn't it strange? They don't measure themselves this way." Langdon Manor has not been able to find much of anything out about Mr. Alexander, only that he divorced in 1907 and died in 1910 at the age of 29. $850.

Next we have a pair of scrapbooks. These were kept by a white man, but one who was of importance during some of the most significant days in the history of the civil right movement, 1962-1965. The keeper was Nicholas deBelleville Katzenbach. Katzenbach served as Deputy Attorney General under President John Kennedy, beginning in 1962. In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson elevated him to Attorney General. He served until 1966, when he was appointed Under Secretary of State. These thick binders are filled with newspaper clippings, photographs, teletype reports, and other ephemeral items. About one-third of the items pertain to civil rights issues. He participated in one of the most notable incidents of the era, the Stand in the Schoolhouse Door. President Kennedy had ordered the integration of the University of Alabama. On July 11, 1963, as the first two black students attempted to enter the university, Governor George Wallace stood in the doorway, blocking access. Standing across from him was Nicholas Katzenbach, there with federal marshals to assure that the students were able to enter. Wallace spoke for a while, but then had no choice but to back down and step aside. Wallace and Katezenbach facing off against each other is one of the more notable photographs of the era. Item 7. $875.

Langdon Manor Books may be reached at 713-443-4697 or LangdonManorBooks@gmail.com. Their website is found at www.langdonmanorbooks.com.