Long Missing Lincoln Letter Returns Home

- by Michael Stillman

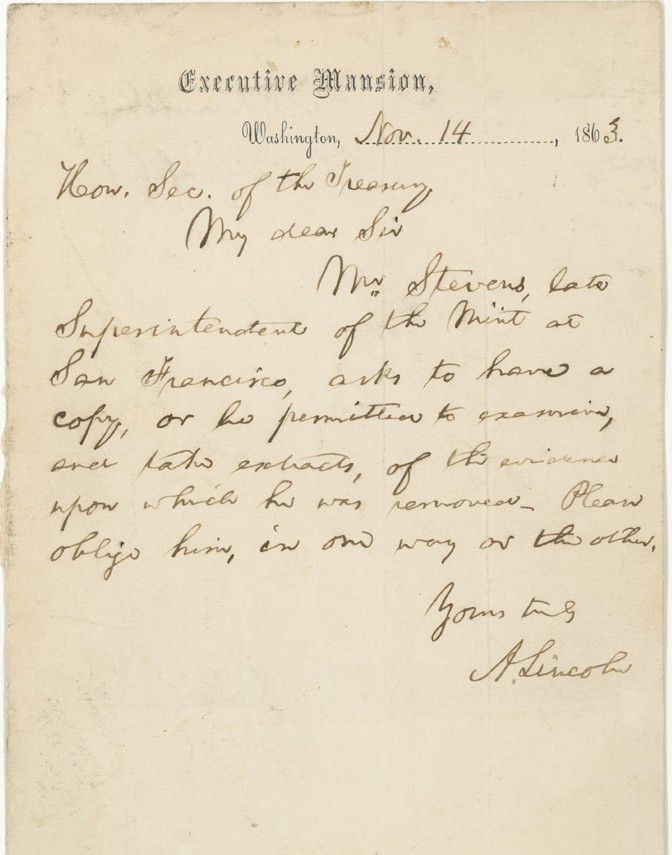

Long lost Lincoln letter from shortly before his Gettysburg Address.

By Michael Stillman

An interesting Lincoln letter, missing from the National Archives for many decades, perhaps longer, made its way home recently, a gift from a collector who purchased it from an online auction in 2006, unaware of its history. The letter was written on November 14, 1863, just five days before the President delivered his Gettysburg Address. While this letter is not so momentous, and is even briefer still than the famed, brief address, it too must have elicited sad emotions for the President. It related to an unpleasant event concerning the son-in-law of a great friend and colleague of Lincoln who had died in battle during the Civil War. To see this relative of a deceased close friend under an ethical cloud could only have been painful to a president in the midst of the terrible burdens of a terrible war.

The letter was written to Secretary of the Treasury Salmon Chase, and it pertains to charges made against the Superintendent of the San Francisco Mint, Robert Stevens. A special agent had been sent to San Francisco to investigate corruption charges against Stevens. He came back with a series of claims, such as hiring unqualified individuals, overpaying some employees and paying others for no-show jobs, overpaying for inferior supplies, encouraging insubordination by workers, and being arrogant and discourteous to his managers. Chase responded by firing Stevens. Stevens protested, and demanded to see the evidence against him. Evidently, he was not satisfied with Chase's response, as several months later, he wrote Lincoln asking help in seeing the evidence. Lincoln thereby wrote this letter to Chase, which states:

My dear Sir

Mr. Stevens, late Superintendent of the Mint at San Francisco, asks to have a copy, or be permitted to examine, and take extracts, of the evidence upon which he was removed. Please oblige him in one way or the other.

Yours truly,

A. Lincoln

Lincoln had appointed Stevens in 1861, a patronage job undoubtedly offered as a result of Lincoln's friendship with his father-in-law, Edward Baker. Baker had emigrated to America from Britain as a young child, lived during his teens in the utopian community of New Harmony, Indiana, and then moved to Illinois, where, like Lincoln, he became a lawyer in the early 1830s. Their paths crossed as a result of their legal careers and interest in politics. In 1844, Baker opposed Lincoln for the Whig nomination for Congress from their local district, and defeated the future president. However, the contest did not have any adverse effect on their relationship, as two years later, Lincoln named his second son, Edward Baker Lincoln, after Baker (young Eddie Lincoln died shortly before his fourth birthday).