Shakers, Maine, and Everything Else A Visit with DeWolfe and Wood

- by Michael Stillman

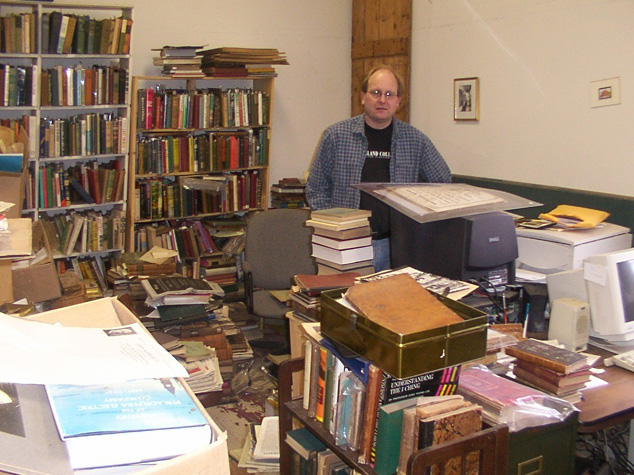

Scott DeWolfe in the quintessential bookseller’s office.

The Alfred community was one of the many to shut down. It closed its doors in 1931, with its members moving to Sabbath Day Lake, another Shaker community in Maine. Interestingly, Scott DeWolfe points out that it didn’t close for lack of members. Alfred was one of the communities still actively proselytizing in the 1900’s. However, the community experienced two devastating fires which forced the eighteen members to make the move. The legacy of the Alfred society with its active recruitment may help explain why Sabbath Day Lake survived to be the last remaining Shaker community.

In 1965, with the end appearing inevitable, and a fear that people would join for the purpose of taking over the communities’ extensive assets when the last of the older members died, the decision was made to admit no new members. Naturally, that sped the decline. However, the Sabbath Day Lake community has more recently decided to accept new members again. Currently, there are four members in total. They don’t make furniture any more, but they do sell herbs and a few “fancy goods.” They even produce an occasional pamphlet or other printed piece as one of the members is a printer. And with there being many other small communal societies that are able to exist in the country, Scott DeWolfe is not convinced that the Shakers won’t survive. He points out that as early as the 1790’s people were saying they wouldn’t survive much longer. “All bets are off,” he exclaims.

DeWolfe doesn’t believe celibacy is the reason for the community’s near disappearance. They were always celibate, even at their peak. Rather, he attributes the decline to their inability to recruit new members. In the early days, they would frequently have entire families join. And while they were celibate, it wasn’t unusual for children in these families to break away, have children of their own, and then return to the fold. And the Shakers also adopted many orphans. They recognized that many if not most would leave the community when they grew up, but some would stay. Still, the primary aim was to convert adults, and while they were very good at doing this in the tough, agrarian society to which the movement was born, they were not as successful in the modern, industrial world.

There are basically two areas of Shaker collecting, Scott DeWolfe explains. One is furniture; the other books, printed material, and other ephemera. The furniture is expensive, very expensive. Furniture generally sells for thousands of dollars. Most other items sell for under $1,000, and often a few hundred or less. It’s an affordable field if you stay away from the furniture.

They estimate there are around 1,000 Shaker imprints. Of course there is also material about the Shakers, not all of it flattering; manuscripts; and various ephemera, from labels to boxes that held Shaker-produced goods, to “fancy goods,” decorative-type items they produced. The rarest and most valuable printed work is A Concise Statement of the Principles of the Only True Church, according to the Gospel of the Present Appearance of Christ by Joseph Meacham. Printed in Bennington, Vermont, in 1790, it is the first printed work of the Shakers. For the first time, it put the Shaker theology into writing. A copy is offered in DeWolfe and Wood’s Shaker Catalog 45 for $30,000. If that’s too pricey for your collection, there are 373 other Shaker-related items available in the catalog.