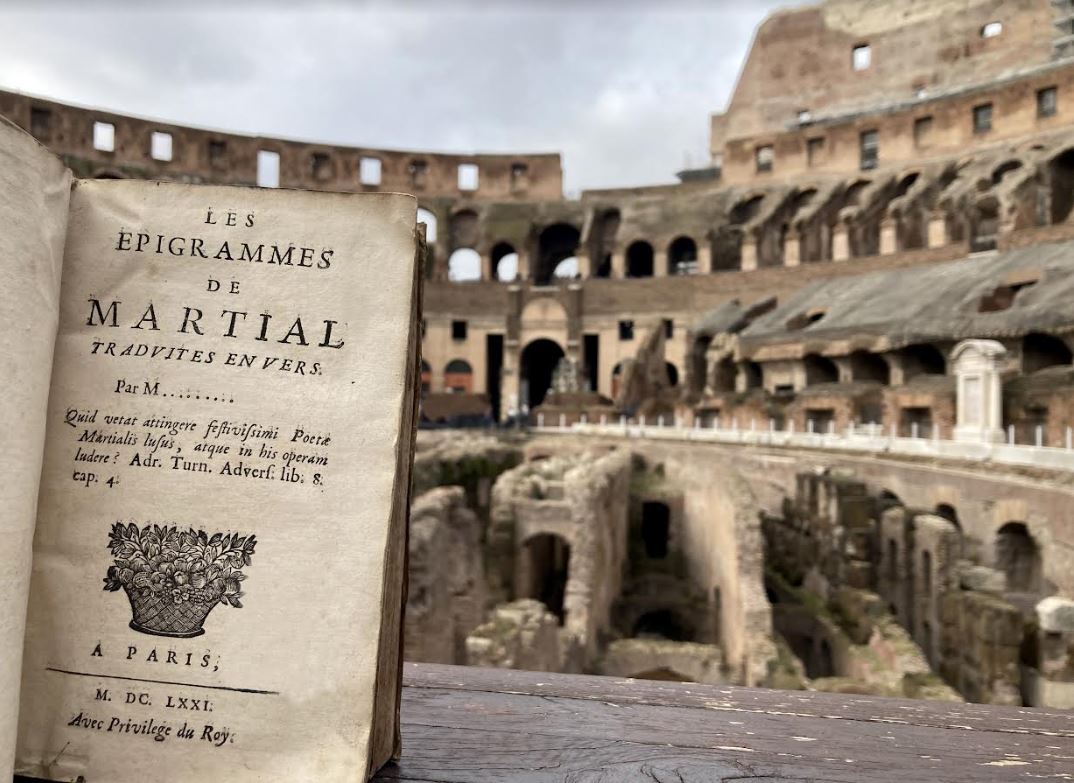

Martial In Rome, the Power And The Glory

- by Thibault Ehrengardt

The Colosseum: Not fun and games, games and slaughter.

I went to Rome, Italy, and I took a picture of a 1671 edition of Martial’s epigrams inside the dreadful Colosseum. This place was once the showcase of the most powerful city on Earth; as you enter it in 2023, you’re almost deafened by the mute cries of 80,000 raging spectators. They were screaming with joy as people were murdered, raped or torn by wild beasts in front of their eyes. These circus games inspired several epigrams to Martial (40-104)—known as “the book of the circus games”. They are not recommended for soft readers.

Visiting the Colosseum is like visiting St Peter’s church in the Vatican. Those places are nothing but unapologetic displays of power. Everything there was designed to make you feel miserable. The cold breath of power blows on your neck as soon as you enter, as if to remind you how insignificant you are. Two thousands years or so later, notwithstanding technological or medical progress, or our travelling to the moon, the impact is still the same. It is a debauchery of means and money with a unique goal: showing who’s the master. “Let barbarian Memphis keep silence concerning the wonders of her pyramids,” Martial writes, “and let not Assyrian toil vaunt its Babylon. Let not the effeminate Ionians claim praise for their temple of the Trivian goddess (...). Every work of toil yields to Caesar's amphitheatre.1” It is the most visited site in Italy today. “What race is so distant from us, what race so barbarous, Caesar, as that from it no spectator is present in thy city? The cultivator of Rhodope is here (...): the Sarmatian nourished by the blood drawn from his steed, is here. (…) The Arabian has hastened hither, the Sabaeans have hastened (...). Though different the speech of the various races, there is but one utterance, when thou art hailed as the true father of thy country.” A pagan Tower of Babel, so to speak.

I had an “arena access” ticket, so I was permitted to step into the arena with a restricted amount of tourists. Here I was, walking in the footsteps of Carpophorus. He was Domitian’s protégé2, and a fearless hunter. “That which was the utmost glory of thy renown, Meleager, a boar put to flight, what is it? a mere portion of that of Carpophorus. He, in addition, planted his hunting-spear in a fierce rushing bear (...); he also laid low a lion (...); and with a wound from a distance, stretched lifeless a fleet leopard.” One day, a lion escaped its master’s grip and created panic among the patrons. Everybody ran away but Carpophorus, who jumped on it instead, and put it to death. What a spectacle indeed! I looked at the nearby seats behind me. They seem so close! The spectators could almost touch the many gladiators who died at their feet.

The circus games had a political dimension. Binging lions, rhinoceros (how powerful was that tusk to whom a bull was a mere ball!) or elephants from the ends of the empire was a way to display Caesar’s power. Even the wild beasts came to die for his glory. The floor of the arena is now gone, and we can see corridors underneath—the belly of the beast. Elevators would send the gladiators, the animals or their victims right in the middle of the battlefield. Representation was the key word of the games. “The pagan and cruel Romans,” our French translator warns before offering the poem entitled Pasiphae, “would often give inhuman and lewd spectacles in the Colosseum, to re-enact the Greek fables.” Pasiphae was Minos’ wife, and when the latter refused to sacrifice a white bull to Poseidon, the God retaliated. He made Minos’ wife fall in love with a bull. So passionate was Pasiphae that she hid inside a wooden cow covered with a cow skin. “The bull approached and started to copulate with it as if with a real cow,” Apollodorus writes. “The young woman then gave birth to the Minotaur.” Many questioned the truth of these fables, and re-enacting them in the Colosseum was a serious matter. “Believe that Pasiphae was enamoured of a Cretan bull: we have seen it,” Martial rejoices, “The old story has been confirmed,” meaning they had a woman publicly raped by a bull. Another wretch had the honour to re-enact the myth of Prometheus: “so has Laureolus, suspended on no feigned cross, offered his defenceless entrails to a Caledonian bear. His mangled limbs quivered, every part dripping with gore, and in his whole body no shape was to be round.” This Laureolus, Martial presumes, had “murdered his father, or assassinated his master, or maybe raped his mother.” Serves you right, you savage!

Man versus lions, leopards versus elephants, women versus beasts, or short-people fighting each other—it goes on and on. I was reading the epigram about those young men who were attacked by a loose lion. They were sweeping away the sand made thick with blood during an interlude. Then I noticed a modern Venus on my right. She was posing in the arena, holding her phone with a selfie-stick—looking for the best view on her body curves, the best pout. Not as much as a bull raping a woman, but this was a dreadful spectacle to behold. Unfortunately, there were thousands of Venuses in the Colosseum that day. Guess that when they post their best shots on social media, 80,000 spectators applauded. The ancient tyrants are gone, but the circus games go on, and the spectators are always asking for more.

Thibault Ehrengardt

1. The English translations are from a 1897 edition available online (www.tertullian.org).

2. The translator of our 1671 edition indicates that Martial is referring to the circus games given by Domitian. Yet, in his article Domitien, spectacles, supplices et cruauté, Cinzia Vismara writes (persee.fr): “The chronology of Martial’s Book of the Circus Games has only been confirmed recently (...). And these poems exclusively depict the games given by Titus to inaugurate the Colosseum.”