What Do Libraries Do with All Those Books?

- by Michael Stillman

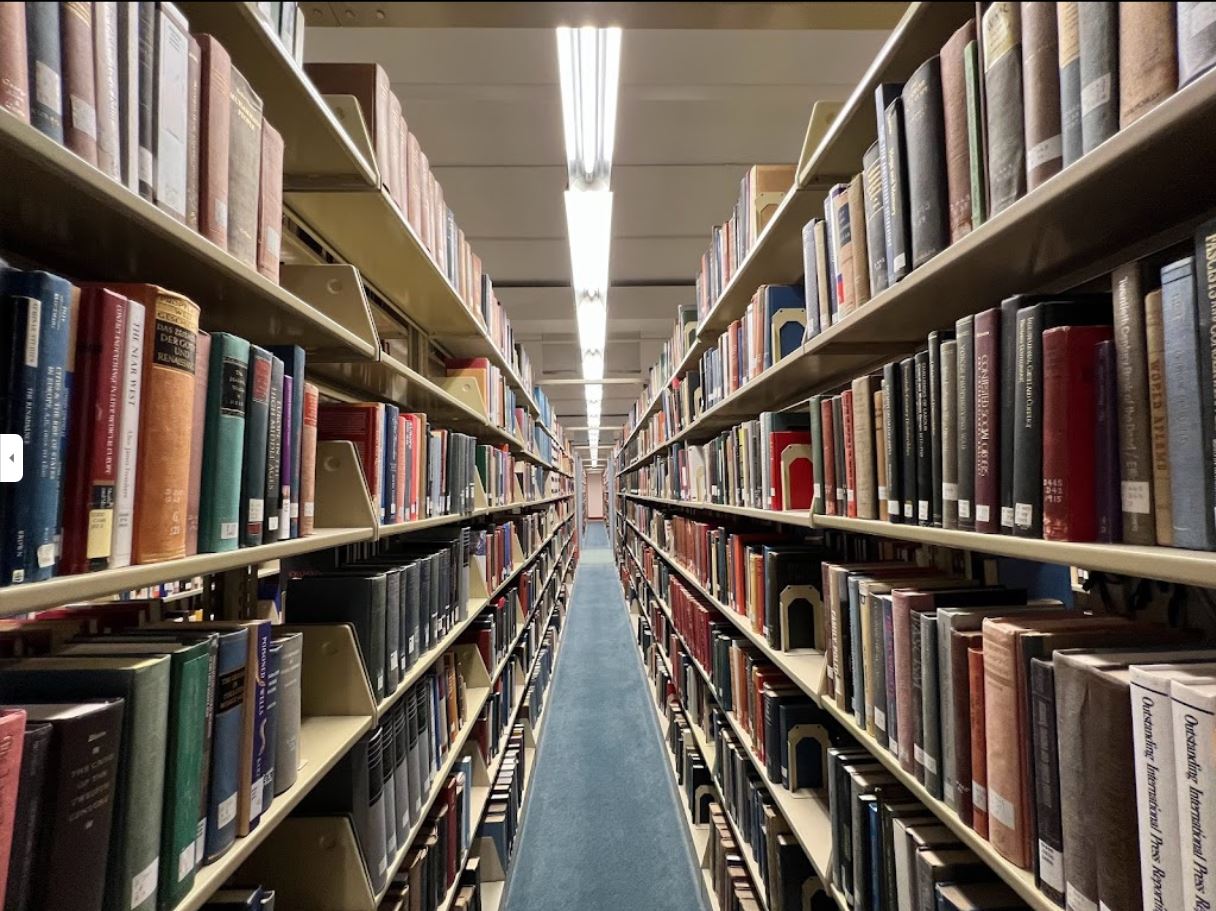

Books in the John Olin Library (Washington University in St. Louis photo).

A Story from Student Life, a student newspaper at Washington University in St. Louis, indirectly highlights an issue libraries are facing more and more, particularly university libraries. It's not an issue anyone much likes to talk about, because it is painful and controversial, but that doesn't make it go away. The issue is what to do with all of these old books in an era when students more and more are using electronic books and resources rather than physical ones.

Washington University is closing its separate chemistry, physics, and earth and planetary sciences libraries. The departments believed the space could be better utilized. University Librarian Mimi Calter also noted that the closings are partly the result of Covid-19 budget cuts and having to hire staff at each library. Most of the material from each library will be transferred to the John M. Olin Library, the main library on campus, though some will go into storage at West Campus. Calter also explained that students in the STEM programs are less likely to use printed material over electronic versions than is the case for fields such as art and music.

Calter said a major issue confronting libraries is a lack of off-site storage. These are off-site buildings where books are shelved so as to pack them as densely as possible. They are generally stored by size to use the minimum amount of shelf space, rather than order of subject which would be more desirable for browsing. There is no browsing in off-site storage, the books have to be brought to the regular library on request by people who know how to find them in the storage area.

Washington technically has no off-site storage. They have a storage building in West Campus, still on campus though off on an edge. Unfortunately, it was not designed for this purpose and has its issues. It has less than ideal HVAC, it is not designed for high-density storage, and frequently has leaks. That is definitely less than ideal.

Associate Librarian Leland Deeds said that at the current rate, storage problems will arise in time. He estimated that if they don't lose any of their shelf space in the current storage area nor receive any unexpected large collections, they would reach 100% of storage capacity in five to seven years. However, he added that as a “rule of thumb,” you don't like to exceed 80% of storage capacity. He also noted that shelving requirements for the books in the main library limits the amount of other uses in that space. As an example, he noted that if they wanted to increase student seating in the library, they would have to reduce the amount of shelving available there.

What is not discussed in this article is the elephant in the room. What happens when storage space is filled? This is a question libraries everywhere face. Presuming some more recent but now out-of-date books with little value are simply tossed out, others will be kept as they have a continuing use, and those that are deemed collectible, of course, will never be tossed out. That means storage requirements can only go up, not down. So then, what happens to this ever increasing number of collectible books? There seems to be only two choices, keep increasing storage capacity or deaccession the books. Neither choice is all that good, and in the choice between two evils, each will have its own constituency.

Those whose job it is to mind the budgets will prefer the deaccessioning route. Library budgets commonly are going down, and some libraries find themselves pushed to reduce their collections and required space, not increase it. Storing books is expensive, as security and climate control measures require much more than just sticking them in some unused space. Limited funds are needed to fill services in higher demand. Many of these books are rarely, if ever, used. Besides, this side will argue, much of the content of these books is now available digitally. You can fit a library in, perhaps, a thumb drive or two, or certainly, in a tiny niche in the cloud. In some cases, where institutions find themselves financially strapped, desaccessing will be about more than just saving money. They may sell some of their books to raise money.

On the other side are the preservationists. They love books. They love learning, history, culture, everything books stand for. They see preservation as a sacred duty. They feel that once something is in a collection, rather than just for browsing, it should stay there forever. Preservationists are also well aware that many of the collectible books were gifts from collectors who were themselves preservationists, which is why they gave their books to a library rather than selling them. They thought they would stay there and be loved forever.

Who is going to win this debate? In a sense, both, though preservationists may not feel that way. Most collectible books will remain where they are unless the institution suffers some major financial difficulty. However, some will be sold, either to save money, make money, or simply to refocus collections. Those who favor 100% preservation will not be pleased, but it is the reality in financially stressful times, compounded by digital access reducing the need for hard copies with a wide array of other sources of information (databases, informational websites, Google, etc.) being available. This is nothing new, just something that is increasing and becoming more public. Their collections are likely to become more focused, which will make some material less relevant. Private collectors will be pleased as some of this comes to market, at least a mild reversal of the long term trend that has seen more and more of the best material move from private ownership to institutional collections. Times change, and so do libraries.