Robert Chevalier de Beauchêne - The Real Fake Story of a Buccaneer

- by Thibault Ehrengardt

Robert Chevalier de Beauchêne was a bold and bloodthirsty buccaneer from New France (Canada). No wonder his memoirs were highly attractive in 1732, especially since they were put together by the popular writer Alain-René Le Sage (1668-1747); but are they authentic? Truth is said to be stranger than fiction, yet some writers still find the need to rearrange it. Not all pirates use swords, some use pens.

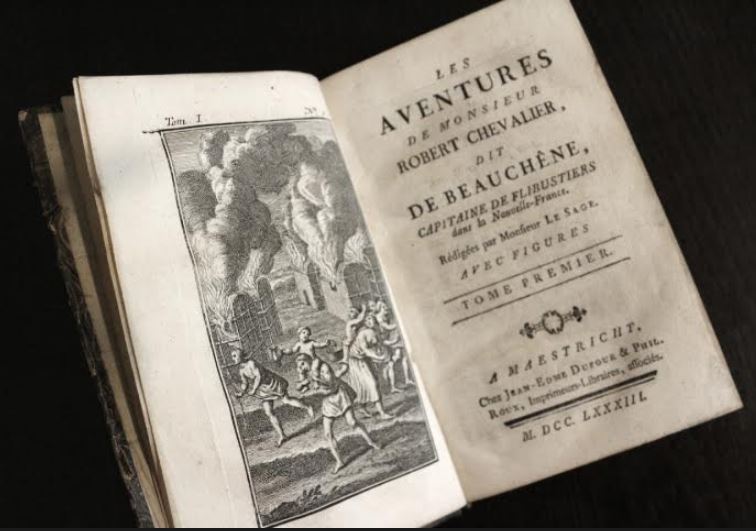

Fénelon states in the preface of Télémaque: “Should Man stand the naked truth, she wouldn’t need the finery she borrows from imagination to make herself known and lovable; but her delicate and pure light doesn’t always flatter man’s sensibility. (...) Here lies the weakness of Man: showing him the truth is not enough, it must be done in a pleasant way.” Robert Beverley’s preface of The History and Present State of Virginia (London, 1705) seems a direct answer to Fénelon: “Truth desires only to be understood, and never affects the Reputation of being finely equipp'd. It depends upon its own intrinsick Value, and, like Beauty, is rather conceal'd, than set off, by Ornament.” Regarding false accounts, he adds: “The French Travels are commonly more infamous on this Account, than any other, which must be imputed to the strong Genius of that Nation to Hyperbole, and Romance. They are fond of dressing up every thing in their gay Fashion, from a happy Opinion, that their own Fopperies make any Subject more entertaining.” This is probably what happened when French novelist Alain-René Le Sage decided to put out Robert Chevalier de Beauchêne’s memoirs in 1732. The author of Gil Blasde Santillane couldn’t resist adding some picaresque dimension to a manuscript he had obtained from Beauchêne’s widow. The first edition came out in 1732 (Paris, chez Etienne Ganeau); yet, in his Essai de Bibliographie Canadienne (Québec, 1895), Philéas Gagnon writes: “This edition, although said to be the first, is yet the second one; indeed, one was previously published in Amsterdam in 1730 by Jean-Edme Dufour, 2 vols. in-12 with plates not signed.” What makes it unlikely is the fact that Beauchêne died in Tours, France, in December 1731. Furthermore, the privilege of the 1732 edition is dated July 22, 1732. Was Gagnon referring to an “avant la lettre/before letters” edition (with the engravings coming without any written indication)? Anyway, the 1732 edition came as a 2 in-12 volumes* with 6 full-page engravings “drawn by Bonnard and engraved by Scotion.” (Gagnon).

* Tome 1: half-title page / title page / 14 leaves / 390 pages / 3 plates. Tome 2: half-title page / Title page / 6 leaves / 363 pages / 3 plates.

Beauchêne’s True Colours

Although introduced by its author as genuine, Beauchêne’s story soon came under suspicion. “Charles de La Roncière and A.-Léo Leymarie believed they were genuine. Gilbert Chinard, Aegidius Fauteux and Gustave Lanctot made thorough researches, and rejected a great part of them,” René Baudry writes. Yet, “our buccaneer is no myth,” Gagnon states, “he was born near Montréal, Canada, where he lived a devil’s life.” Baudry gives more details: “It is now certain that Beauchêne truly existed, and that he left a manuscript; but his account has been considerably reworked by Le Sage. He was born at Pointe-aux-Trembles, in Montréal, Canada, on April 23, 1686, son of Jacques Chevalier and Jeanne Vilain.”

Le Sage’s narrative abruptly stops after Beauchêne looting Antigua, in 1712: “The rest of Beauchêne’s memoirs is in Tours, with his wife,” the author concludes. “If she sends it to me, then I’ll give it to the public.” But she apparently never did. According to Le Sage, Beauchêne, now a rich man, went to France, at an unknown date. There, he lost a part of his fortune through gambling, before going to Saint-Malo and then Brest. Le Sage writes: “While in Brest, he quarrelled with an Englishman on December 11, 1731, and found in this fight a death he had defied with impunity during many bold boarding actions.” Baudry adds: “We have a death certificate for him, dated December 1731, and recorded in the parochial registers of Brest.”

Half the Truth

At one point, Beauchêne takes an English ship on the Gambia River, Africa, and rescues two French prisoners, including one Count Monneville. The latter is compelled to tell his story—in a strict picaresque fashion (Gil Blas is considered as a typical picaresque novel). Monneville’s story occupies half the book, and is obviously fictitious. It yet contains a few interesting passages regarding New France, as noted by Gagnon: “Beauchêne gives some surprising details about the way people were married in Canada in the late 17th century.” The said passage reads: “Celibacy is a crime of lease-Majesty in the colonies, so every newcomer must find a companion upon arrival. Here is how we proceed: Miss Boubon, who runs the house where women fresh from Paris are sheltered, builds up couples at random. Happy is the one who receives a healthy and sane wife!” Every couple was granted £50 in the name of the King, and was sent into the wilderness. This scene, Baudry notes, was inspired by another relation: Voyages du Baron Lahontan dans l’Amérique Septentrionale (see Letter II, Tome 1—La Haye, 1703).

The book is divided into 6 chapters (3 for each volume). Beauchêne’s own story occupies the first two ones and the last two ones. They represent the most interesting part of the book, describing a terrible and revengeful boy fascinated by death: “I wasn’t even seven yet, and there was already not a dog, a cat or a hog left alive in the village”—the typical profile of a psychopath. As a matter of fact, when some Iroquoians raid his village, our boy runs to them to be taken hostage, even helping them to carry their booty away. After several years among the “Savages”, he abandons his troop to join the buccaneers, longing to quench his thirst for blood and violence—and he does. From New France to Saint-Domingue to Jamaica to Africa, we follow him in his adventures. Robbing, killing, looting and kidnapping, Beauchêne goes through misery and fortune, loses friends and kills many enemies. This is a typical buccaneer’s life, senseless and brutal, far from any romantic vision, and probably much more relevant.

The first edition came out under the title Les Avantures (sic) de Monsieur Robert Chevalier, dit de Beauchêne, Capitaine de Flibustiers dans la Nouvelle France. It was later changed in a few editions into Les Aventures du Chevalier de Beauchêne. Baudry lists several editions known to him: 1733 (Amsterdam, Aux dépends de la Compagnie), 1780 (Maestricht, chez Dufour & Roux—apparently not in Sabin’s), 1794 (Lille, chez FJ Lehoucq). The copies taken from the complete, or chosen works of Le Sage (Paris, 1783—for example), featuring two engravings only, are less valued.

Conclusion

The fictitious parts do not really alter the value of the book, probably because Le Sage is a recognized writer today. A very nice copy of the 1783 edition bound by Antoine Chatelin (early 19th century), was sold for 800€ in Paris in 2007 (vente Jean-Paul Morin—Pierre Bergé & Associés). In fact, Lesage’s rearrangements have given another dimension to the book: “They form a new frame, the frame of travel literature,” writes Emmanuel Bouchard in the preface of the 2018 critical edition of Beauchêne’s adventures (Paris, H. Champion). Somewhere in between truth and fiction, literature and fraud, the life of this bold and scary buccaneer... lies.

Thibault Ehrengardt