Book Review: Where Have All the Copies of Robert Burns' First Book Gone? Here is the Long Answer

- by Michael Stillman

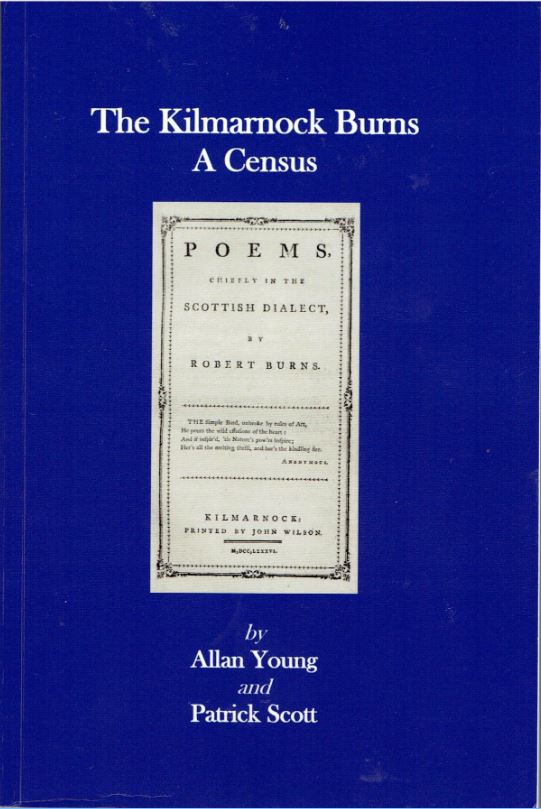

The Kilmarnock Burns. A Census.

In the summer of 1786, 27-year-old Robert Burns delivered his first set of poems to a local printer. Burns was the son of a farmer, one who saw little future for himself in his native Scotland. He planned to emigrate to Jamaica. He hoped that his book of poems might earn him enough money to pay the fare.

While unknown to the public, Burns had some local recognition among those who had seen manuscripts of his poems. Friend and lawyer Gavin Hamilton urged Burns to have a book of poems published. So began the career of Scotland's favorite son, with the printing of his first work, Poems Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect. The first edition ran off the press around the first of August of 1786.

Burns had 612 copies printed. That sounds ambitious for an unknown poet. It is reminiscent of the Bronte sisters, later renown as novelists, ambitiously publishing a book of poems jointly, their first work. They printed 1,000 copies and sold 2. Burns was not such a dreamer. He needed money to print them and so first rounded up a collection of subscribers. Finding 600 of them in Kilmarnock, Scotland sounds like an overwhelming challenge, but while Burns had no official benefactors, he had friends who were willing to buy up a whole lot of copies and resell them. By June of that year, Burns already had 350 subscriptions. Robert Aiken bought 145 copies, almost a quarter of the print run. Robert Muir bought 72, Burns' brother Gilbert 70. Gavin Hamilton ordered 40 copies. Just seven people purchased two-thirds of the copies. By August 28, only 13 copies remained, by September 6, all had sold out. The success was so great that by September, Burns was working on a second edition of 1,000 copies, and his plans to emigrate to Jamaica were canceled.

The year 1786 was a long time ago, 231 years to be exact. What has happened to those 612 copies of Burns' first book since? Most, undoubtedly, met their unfortunate fate years ago, but what about the survivors? Answering that question seems an unimaginably difficult task, and yet a book has just been published that takes on that enormously difficult challenge. It is thorough, detailed, and obviously a labor of great love. It is the work of a retired Scot living in Florida, Allan Young, who began the task in 2002, and Patrick Scott, an Emeritus Distinguished Professor of English at the University of South Carolina, home of a major Burns collection. If you are a collector of Burns, someone who admires his work, or just someone who loves a good mystery, you will be completely fascinated by this book of detective nonfiction.

The authors have used every tool of searching to locate surviving copies, not just those in institutional libraries, but those hidden away in private collections. Often, this has required looking back at old records, such as long ago auction listings and old newspaper articles, to trace where they have gone. The authors traveled all around England and North America to view surviving copies, so as to be able to match them up with copies described somewhere perhaps over a century ago. The result is an amazingly thorough description of every copy publicly known to exist, along with information on a few other copies which almost certainly remain in the hands of some quiet, unknown collector.

As of 1996, Ross Roy, in writing about an exhibition on the 200th anniversary of Burns' death, estimated fewer than 70 copies survived. By 2009, Young had located 71 of them. As of this writing, that number has increased to 84. The authors estimated there could be as many as 25-30 more copies still extant, based on old auction and other descriptions of copies which likely still survive but whose whereabouts they have not yet been able to determine. Their book is entitled The Kilmarnock Burns: A Census, and Young and Scott have divided it into three sections – a census of institutionally held copies, where they were able to gather and include detailed information about location, condition, and identifying aspects of each of these 69 copies, a private ownership census of 15 copies, where information is mostly more spotty and several owners have wished to remain unidentified, and a chronological order report of all information they have located about copies, both those in known collections and those that are lost or whose whereabouts is unknown. Among the last group, there is information dating from April 1786, a listing of early subscribers, up to the current year.

The majority of the copies, 48, turned up in the United States. Twenty-five still remain in Scotland. Another 6 were in other parts of the U.K., 3 in Canada, one in Australia, and only one in a non-English speaking country, Switzerland. Only four still have original wraps, and of these, two are bound in and in one they were used under a marbled cover. There is one copy of unbound, uncut, folded sheets. Twenty-five have early bindings, most are in later fine bindings. It was thought that would make them more valuable. That was a mistake.

Among the many anecdotes about these copies, here are a few we found particularly interesting. A private collector in Scotland owns a copy once belonging to Gavin Hamilton, likely his personal copy rather than one he resold. On the page dedicating the book to him, Hamilton has written his name. It also contains two manuscript poems in Burns' hand bound in. Sadly, the top half inch of the title page has been sliced off. It likely once held an inscription. It was still in its original wrappers in 1850 when an Edinburgh bookseller had it rebound. According to the owner, "It is in wonderful condition."

Compare that to the copy at Balliol College, Oxford. The description of this copy reveals, "the text is grubby, showing evidence of a lot of reading throughout... The bottom left hand corners of openings are particularly dirty, presumably from grubby thumbs, and there are smudged fingerprints. Some pages have spill marks on them..." It could be worse. The Dunfermline Carnegie Library copy is missing the first 48 pages. It was being used by a barber to sharpen his razor, ripping out pages one at a time, when it was rescued by a traveling salesman.

Harvard University has a copy that once belonged to Harry Elkins Widener. Widener was a noted bibliophile, the son of U.S. Steel and American Tobacco wealth. However, it was given to Harvard by his mother, not Harry. Harry Widener went down with the Titanic, just 27 years of age.

One of the British Library copies was once in the library of bibliographer Thomas Wise. Wise was the master forger, who not only copied existing books, but created pre-first edition ("true first edition") copies. We will presume the British Library examined this copy carefully for authenticity.

One of the National Library of Scotland copies actually came from America, or at least back from America. It was part of the collection of Robert Hoe. He was a major manufacturer of printing presses in the 19th century and his sale in 1910-11 was by far the largest auction sale in American history up to that point.

The Florida State University copy comes from one of the luckiest book collectors of all time. It's all about timing. To the rest of the world, Jerome Kern is known as a songwriter, writing Ol' Man River and other classics. To bibliophiles, he is known for his immaculately well-timed auction. He sold his collection for staggering prices in 1929, at what would be the top of the market for several decades. Shortly thereafter came the stock market crash, and then the Great Depression, and the value of books, like most everything else, plummeted.

The Kirkcaldy Library copy was the gift of the daughter of John Nairn. Nairn is not well-known outside of Scotland, but he was one of the land's most successful businessmen. He didn't invent it, but made a fortune manufacturing linoleum. If your old house has linoleum floors, it may have helped purchase this copy.

The Lilly Library has one of only five copies with uncut leaves. It was sold by the estate of Frank Bemis to legendary bookseller Dr. A. S. W. Rosenbach, who in turn sold to to Josiah Lilly. Lilly left it to the Lilly Library at Indiana University. Later, it was determined that this apparently perfect copy was made up of sheets taken from multiple copies. Whether one of these owners, or a previous one compiled the copy is unknown. Mr. Lilly would not appear to be the culprit since it is unlikely he would have purchased a defective copy.

The University of South Carolina copy was once owned by Apsley Cherry-Garrard. Cherry-Garrard was the Antarctic explorer who accompanied Robert Falcon Scott on his ill-fated attempt to be the first to reach the South Pole. He not only finished second, but died in terrible weather trying to make it back to the ship. Cherry-Garrard, fortunately, did not accompany Scott to the Pole, but barely survived a side journey that took the lives of his companions. He wrote about it in The Worst Journey in the World.

And then, there is one copy in the hands of a bookseller, Jonathan A. Hill Bookseller. If you would like a copy, this one is still available. It is described as a "fine copy" and is available for the price of $85,000. Incomplete copies come up occasionally at auction for not notably high prices, but a complete copy in fine condition is highly valuable.

Burns collectors will be fascinated by this book, but it is a great read for all who like old books and find a where-is-it-now mystery exciting. A copy may be purchased from Amazon through this link: click here. If you are aware of any missing copies, or otherwise need to contact the author, Patrick Scott may be reached at scottp@mailbox.sc.edu.