Ernest Renan, The (Emotional) Life of Jesus

- by Thibault Ehrengardt

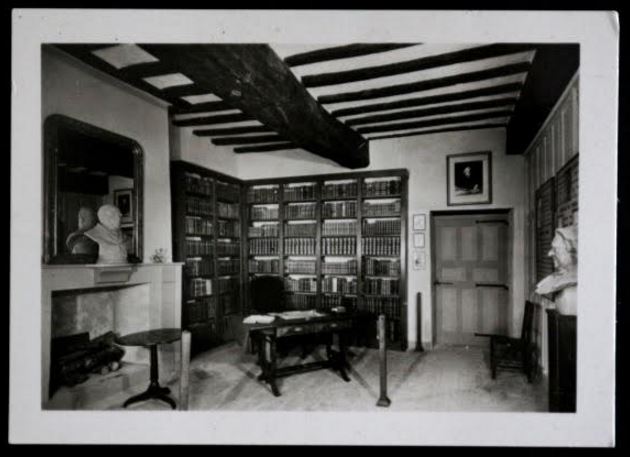

Recreation of Renan's university office in his birth home.

Regarded as the “first historical biography of Jesus”, Renan’s Vie de Jésus is a very emotional book. As such, it deeply irritated the historians, while selling like hot cakes. Historians and feelings had never got along very well, anyway—just like Jesus and the Pharisees.

Big Man with Big Beard

Once the country of the Most Christian Kings, France has now become hostile to the mere idea of God, and only the bold dare mentioning it in a discussion—that’s when they are automatically identified as the nostalgic conservators of an old stinky morality, or as plain idiots. And here comes the unavoidable question: “So, you really think there’s a big guy with a big white beard sitting in the clouds, looking at you?” Don’t try to argue. Just laugh casually: “Ha, ha! Yes, and sitting next to him is Santa Claus!” Then grab an appetizer and shift to a topic that really rocks: the weather. Yet, there was a time in France, when you couldn’t even suggest that Jesus was an ordinary man. Thus, when Ernest Renan (1823-1892) published the “first historical biography of Jesus Christ”1 in 1863, he created a nationwide scandal that even reached the Vatican. Different times, different ways.

The Book

When Renan announced the publication of his Vie de Jésus in Juin 1863, people queued outside the bookshop of his publisher in Paris to buy their copy. “The book being expensive (7,50 Francs) and thick (in-8°),” Perrine Simon-Nahum writes in 20072, “the publisher had ordered a very humble first edition (10,000 copies).” But the book met with immediate success. “Between 1863 and 1864, it was published twelve times. (...) Between 1864 and 1944, some 430,000 copies were sold. By 1947, it had been translated into 12 languages.3” Renan became the second most well paid writer in France, just after Victor Hugo—the latter earned 300,000 Francs with Les Misérables, while Renan earned 195,000 Francs with Vie de Jésus. In September 1867, Renan reworked his preface for the thirteenth edition, “which is the reference today.” (Simon-Nahum). There is also a fully illustrated (60 realistic engravings) edition dated from 1870. In March 1864, came out a popular edition bearing another title, Jésus; it is a shorter (262 pages) and smaller (in-32°) edition, with no footnotes, and from which the most complex passages have been deleted—or simplified. This approach earned Renan a few more enemies. At the end of the day, his book is not rare, and can be found easily. Some rare bibliophilists’ copies, finely bound, are also available.

The Author

When his book came out, Renan was not a “nobody”—a renowned researcher, he had just been elected to the chair of Hebrew at the Collège de France; in the complex political context of the time, he was identified as “the symbol of the laic and republican threat.” (Simon-Nahum). Thus, following his scandalous inaugural speech, Minister of Public Instruction Gustave Rouland immediately suspended him: “You have indeed systematically denied the most essential dogma of our Christian faiths (...). It is therefore impossible for the government that wishes both peace of consciences and public peace, not to notify its legitimate and deep concern.” The law separating the Church from the State wasn’t voted until 1905 in France, and politics were still involved in religious matters. Consequently, the Emperor himself, Napoléon III, informed Renan that he couldn’t tolerate “one of the basis of the Christian religion to be denied.” In his speech, Renan called Jesus, “an incomparable man4, so mighty that I would not contradict those who, hit by his exceptional achievements, call him God.” This provocative statement owned him many detractors—a librarian from Dijon has listed 214 pamphlets published against him at the time. He was called a blasphemer; some claimed he should be burnt alive, and when the archbishop of Reims put a ban on his book, Pope Pius IX congratulated him in person! And on June 11, 1864, Renan was officially revoked from the Collège de France.

1.Vie de Jésus (Paris, chez Michel Lévy frères, 1863).

2. In the article Le scandale de la Vie de Jésus de Renan, published in the periodical Mil Neuf Cent (n°25).

3. Including in English as The Life of Jesus (London, Trübner & Co.—1864).

4 A reference to a famous speech by the French preacher Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet (1627-1704).