Dr. Charron, Barking Fools...

- by Thibault Ehrengardt

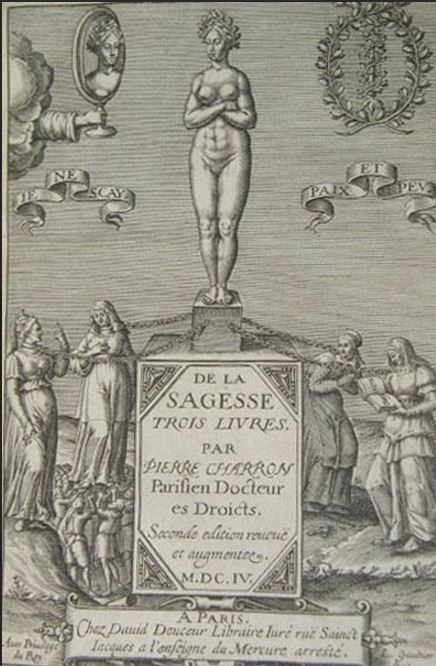

Wisdom graces the cover of De La Sagesse (of wisdom).

The Elveziers

Bastien praises the first edition of 1601: “All the following ones are inexact and incorrect, especially the Elzevir one of 1646 (or without date), which is highly regarded, mostly because of the neatness of its impression; but the text is often altered, and disfigured by the punctuation. When will we find some bibliographers instructed enough to step away from the ordinary routine, and to guide the public opinion according to the merits of the authors and their works rather than to follow fashion? Indeed, the second—and softened—edition came out posthumously in 1604 (Paris, at David Douceur). But as soon as 1606, Simon Millanges reprinted De La Sagesse following the copy printed at Bordeaux. And according to Alphonse Willems, “the Elzeviers followed the text of the first edition, Bordeaux (Millanges), in-8°, although the author had later added and corrected many passages. But as the majority of these changes had been dictated by the necessity to prevent the censorship of La Sorbonne, it comes as no surprise that the Protestant publishers (the Elzeviers—editor’s note) did not care, and stuck to the first edition.” Furthermore, Bastien seems to think that the 1646 edition is the same as the one without date, but Willems makes it clear it is not: “The third edition came out without date; it was printed in 1659 (...). Some collectors favour this one, which is said, maybe wrongfully, to be the rarest one.” On this matter, Brunet is positive: “This is the less common edition of the four given by the Elzeviers.”

The Elzeviers were not the only ones to print Charron’s book. In 1657, Jean Iournel put out an edition in Paris, “following the true copy of Bordeaux.” The foreward reads: “Books are like rivers, which water becomes less clear and pure as it runs away from its source; (...) this had happened with this book, (...) and it forced me to look for the first edition given by Mr Charron in Bordeaux in 1601, at Simon Millanges’.” Brunet praises the publishers who not only followed the first edition, but also added the changes of the second one—not before the early 19th century. “Their editions are more complete,” he says. Anyway, Bastien’s edition of 1783 remains a very nice and well-printed work (a few copies were printed on Holland papers), and the instructive short biography of Charron itself makes it a valuable edition.

A Foolish Jesuit Barks At Charron

Neither the first nor the second editions of De La Sagesse were to satisfy the theologians of La Sorbonne. “They portrayed it as an overthrow of the revealed religion,” giggles J. Duvernet. The complaint was introduced to the magistrate of Le Châtelet whose “understanding was even lower” (Duvernet), and the controversy started to spread on the warm body of Charron. Fortunately, the president of the Parliament, Jeannin, defended Charron’s book. “He praised it with authority, and discussed it as a statesman,” says Duvernet. Backed by President du Harlay, Jeannin declared De La Sagesse “a good book for the state” (Chaudon). But the theologians had not spoken their last word. The worst opponent to Charron’s book was a Jesuit named Garasse, who accused the philosopher of “brutal atheism”, and of “being subject to sensual and guilty melancholies.” His head, claimed the Jesuit, was “full of crayfishes.” Duvernet did not like Garasse. “When this idiot printed this nonsense,” he underlines, “Charron had been dead for twenty years.” Yet, the quality of his work had already earned him some supporters. Indeed, De La Sagesse, though suffering from a somewhat rigid construction, is a breath-taking reading—especially the first two books. The style is unique, strikingly modern, the expressions priceless, and the meaning deep and thought provoking—just like Montaigne’s Les Essais. According to some specialists, his book is announcing people like Bacon, Descartes and Pascal. In fact, just like Montaigne’s Les Essais, De La Sagesse is a must-read to anyone trying to understand the philosophical revolution that took place during the next two centuries. “Several learnt people took his side against the calumnies of the Jesuit,” explains Chaudon. History proved them right. As we say, only a foolish Jesuit barks at a flying wise.

Thibault Ehrengardt