Yves S. - A Reasonable Pessimist

- by Thibault Ehrengardt

Book collectors, like old books, are aging rapidly.

Yves S. is a well-educated man who could be described as a reasonable passionate: “Many people in the old books business are poets,” he smiles, “or old guys.” And Yves S. is neither one nor the other. Aged 35, he is a down to earth collector who always tries to buy at the best price, spending hours behind his computer screen to spot the best books worldwide. He even launched a website, and wrote a few studies over this allegedly dying niche market, old books.

Books are not cool

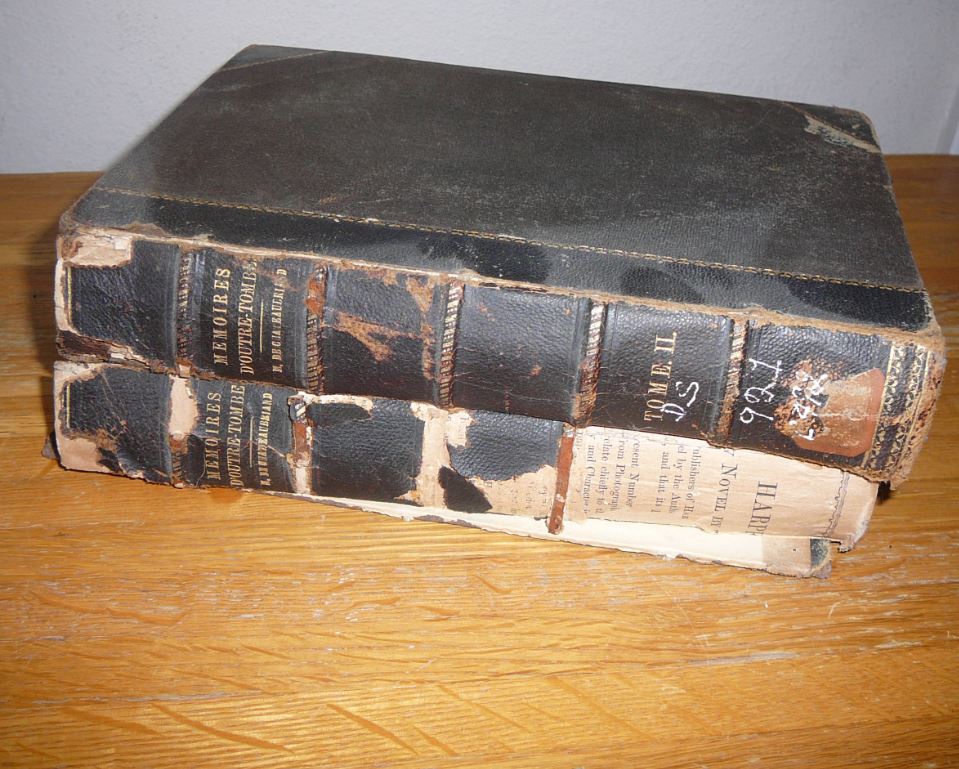

“When you tell your friends you collect old books, they imagine a pile of moist and dirty paper, eaten by rats in a dusty cellar. That’s how people see books in France, like an old sour-tempered guy's pastime; books aren’t glamour any more.” Yves S. is a lucid man who bought his first 18th century book when he was still a teenager: “It was the abridged History of Henault,” he recalls, “a wonderful book that still features among my all time favourites—I’ve read it six times.” Yves is fond of history books—but not all history books. “I read all the books I buy, and I never keep a boring reading, no matter how rare it is.” He also thinks highly of Velly, Villaret & Garnier’s History of France (1767-1786): “History books that stick to facts are usually boring, and there are a lot of them—I love Garnier’s book for the sociological discussions it contains.” When the author goes straight to the point just like the Duke of Saint Simon—Louis XIV was a man of mediocre intelligence, read the forewords of his works— it is even better. “I love books that deal with the evolutions of society that led to the French Revolution in 1789; also those that criticize the system from inside.” Curiously, he doesn’t like Voltaire—whom he defines through a handful of plays nobody reads any more, and “a nice little novel”, Candid, or the Philosophes des Lumières, but he sure appreciates the bad faith of Bussy Rabutin. “I guess he was an awful man... But his writings are brilliant!" It is even more pleasant to find a work of Necker bearing the arms of his worst enemy, the Comtesse de Provence; or Les Liaisons Dangereuses with those of Marie-Antoinette (which lies on a shelf of the NLF). As you might have guessed, Yves S. enjoys life’s ironies.

Family Reason

The history told in the books Yves S. collects was never really his, or his family’s—indeed, he is from an ordinary linage. Thus, he enjoys the ironic situation: “In those days, I couldn’t have possessed a book with arms—I would have been sent to the gallows right away,” he laughs. Books have always been present in Yves’ family, though. His father still collects architecture books, for instance. And he does it his own way, trying to replicate the famous Mark J. Millard Architectural Collection and its 160 must-have titles.“He’s got one hundred so far,” tenderly smiles his son. Books seem to be a way to share some good times with his father, as they discuss their next purchases together. And they always keep a cool head. “I leave some 300 orders a year, to buy 2 or 3 books,” confesses Yves. “I always leave very low orders—and when I win, it’s always a good bargain. Money is too hard to earn to be spent stupidly. And I watch auctions all over the world, especially in America where there is less competition over French books.” But can a collector be wise; or a passionate reasonable? Yves loves La Rochefoucauld’s maxims too much to ignore that collecting old books, like everything else, is an egotistic pastime. “We buy books because they give a good image of ourselves. In our distorted minds, the value of our books equals our own value.” Thus, it would be vain to think one is able to keep his passions under control; but they still can be regulated.

Study Downfall

Yves works for an international company and hardly understands how people behave in the book business. To him, most booksellers are poets—and it sounds a bit paternalistic in his mouth. They are not logical enough, so they usually get nowhere fast. Yves is different, a logical man. As a matter of fact, he has mathematically studied the old books market, made some prospects just like in any ordinary business. He’s collected lists of clients from various booksellers, got close to several auction houses like Sotheby’s or Christie’s, has analysed their results, inquired about the biggest booksellers of Paris, and eventually launched his own website that gives access to many booksellers' catalogues and to a calendar of upcoming auctions. And he made conclusions. “I’ve found out that there are between 2 and 4,000 people who buy old books in France. I even estimated the total value of old books in France to 60 billions euros—most of it lying in the National Library of France, of course.” All these calculations made a pessimistic book lover out of him: “Book lovers, just like booksellers, are isolated, and generally confined to their own fields of interest. It is very hard to federate them. Furthermore, they are mostly old people who will die soon. Nobody really cares about books. Our elites are turned towards mathematics exclusively. I work with a lot of these guys—they don’t know anything about history, not to mention literature—and they don’t give a damn; they don’t even pretend. Nowadays, you don’t send a positive message when you say you love books.” About the impressive—and apparently successful—book fair of Le Grand Palais, set up every year by the SLAM, he says that it costs a lot and that it only attracts old guys. “I think that within the next two generations, nobody will buy old books any more.” But reason isn’t always a guarantee of success—or the vector of truth. And though busy and logically built, Yves’ website hasn’t kept all his promises.

Booksellers

Times are hard, indeed. Not for old books only. And we all know that culture suffers the most during crisis. Yves S. knows of a man who used to work as an executive director and who left everything to become a bookseller. “He’s happy. He says he makes almost as much money as he used to... But I wouldn’t like to be in his shoes when he retires. I finance a bookseller myself; I pay for his investments. He makes no money at all. I tell you, a lot of them are poets.” And there would be no future in the book business. “Well, my studies show that books over 5,000 euros tend to get more and more expensive, while those under 500 euros are losing value by the hour. The problem is that the latter represent the vast majority of the market—they suffer from two factors. First, the booksellers’ margins are too important. They need to make a 150% margin to survive, because of taxes. But buyers don’t care, and buy from the same source: auctions. Second, the Internet has unbalanced the supply and demand equilibrium, and prices are going down. It is so easy to access books nowadays, that the role of booksellers is more and more questioned.” There are still a lot of booksellers around, no? “Yes, and they don’t live good”, underlines Yves S.

But fortunately, unlike reasonable men, poets don’t live from bread alone... but from old books too.

Thibault Ehrengardt

More articles: reliuresetdorures.blogspot.fr