Travel in Jamaica: Buccaneers at the National Library in Downtown Kingston, in the Year 2012

- by Thibault Ehrengardt

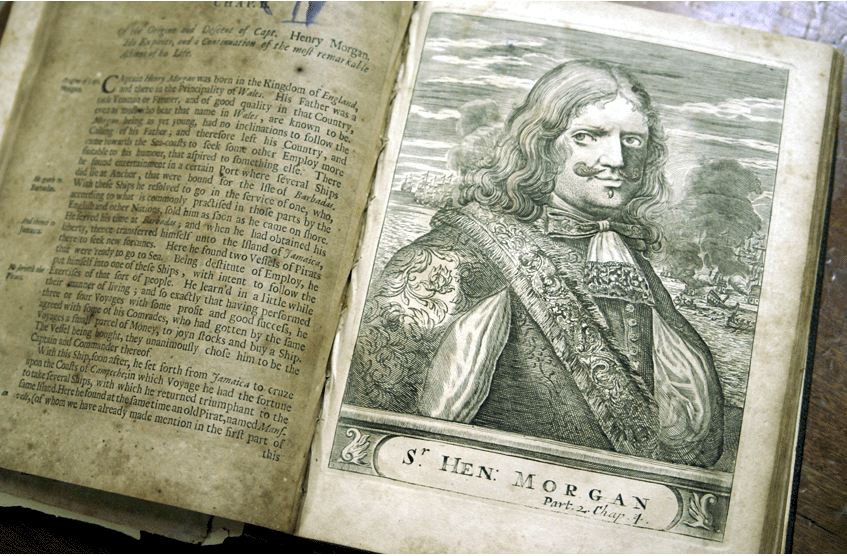

The “honorable” Sir Henry Morgan.

The following editions were then “corrected”, like a very peculiar one I came across at the NLJ. It is an in-12 volume entitled The History of the Bucaniers Being An Impartial Relation of all the Battles, Sieges and Other Most Eminent Assaults committed for several years upon the Coasts of the West-Indies by the Pirates of Jamaica and Tortuga. Bound in full calf (late 18th century binding) and rebacked, it features a remarkable folding frontispiece with the portraits of four buccaneers, obviously reproduced from the 4° edition. It was published in 1684 in London by the same Thomas Malthus. The title page carefully reads : “very much corrected from the errors of the original” but nevertheless boasts of narrating the “unparalleled achievements of Sir H.M ” - the use of initials might explain the absence of Henry Morgan’s portrait from the frontispiece.

Morgan is an ambivalent figure. Considered as a hero by some, as a petty pirate by others, he played a key role in the history of Jamaica. “Jamaica would not presently be ours, had it not been for the buccaneers”, the historian Edward Long wrote in 1774. Long, a Jamaican resident, was a virulent apologist of Sir Henry. Buccaneering was perceived by some colonists as a necessity dictated by the laws of survival. Governor Modyford, for instance, started to fight the buccaneers when he came to the island. He soon deplored this “terrible mistake”. Not only did they protect the island from the French buccaneers of Saint-Domingue (and the nearby Dutch islands as England was at war with Holland) but they also made it prosper. The riches they stole from the Spaniards were coming through Port Royal, the wealth of which they contributed to. Port Royal became one of the most important ports in the West-Indies. Merchants turned the city into a business centre where rents became as expensive as in the best parts of London. Buccaneering had benefited trade for a while, but it couldn’t last - the merchants needed strict regulations to earn more money and they eventually took over. When the King sent Sir Henry back to the island in 1675, he ordered him to eradicate buccaneering. The new Deputy-Governor then sent several of his former associates to the gallows of Port Royal... while planning some illegal expeditions in the taverns of Port Royal. He died in 1688, aged 53. The physician Hans Sloane, who attended him in the last days, described him as “lean, swallow-coloured, his eyes a little yellowish, and belly a little jutting out or prominent... much given to drinking and sitting up late.” On August the 26th, 1688, he was buried close to Port Royal. The cemetery sunk into the bay during the earthquake of 1692 and Sir Henry’s bones now lie somewhere at the bottom of the ocean.

I never had much time to go through this unusual in-12 edition. Abridged it must be as it is so small a book, probably rewritten too. This aside edition proves that the book sold pretty well – hence the smaller format, cheaper. Another proof of its popularity lies in the fact that the publisher put out a “second part” to The History of the Bucaniers. It relates the terrible expedition of the Jamaican buccaneer Captain Sharp in the South Sea, in the year 1679. It was written by Basil Ringrose, himself a buccaneer, who eventually died in a skirmish against some Spanish troops in Santa Pecado in 1686. The famous sailor William Dampier, another buccaneer from Jamaica, tells us of his friend’s death whom he found lying naked on the ground amongst other buccaneers, “so mutilated by the Spaniards that we could hardly recognize any of them.” Mr Ringrose was the author of the second part of The History of the Bucaniers, that gives so much credit to Mr Sharp. He was not enthusiastic about the Santa Pecado expedition but had no choice to accept it or to starve to death. Here is why these books became classics – the authors were part of the action. Esquemeling in particular, takes his readers to the heart of buccaneering. Everything here is but violence, scenes of torture, adventure, violent deaths by gun, sword or at sea – and it is (almost) all true. Ringrose’s text is illustrated with many sketches of maps, pleasing but not breathtaking. His work, as a matter of fact, remains up to this day a mere “follow up”. Esquemeling’s work can not be overshadowed. The two parts are often bound together. It is the case with the JNL copy.