Is Mentioning a Book's Provenance a Legally Actionable Invasion of Privacy?

- by Michael Stillman

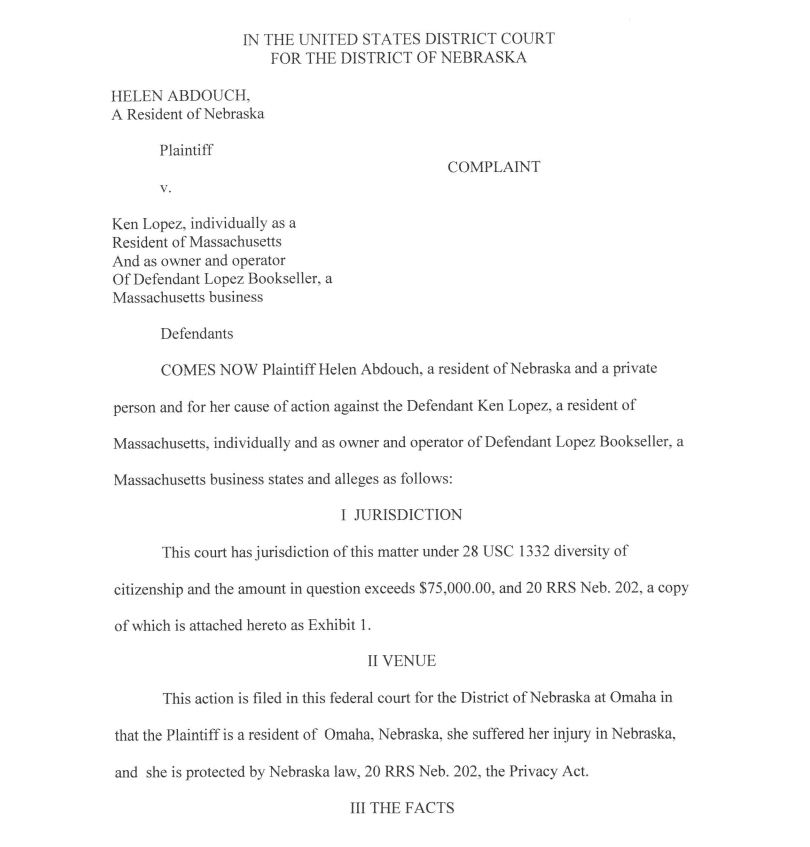

Page one of Helen Abdouch's complaint.

For booksellers besides Mr. Lopez, this case raises all sorts of issues if Ms. Abdouch were somehow to prevail. First, as to her privacy, Ms. Abdouch has not asserted that the book was illicitly taken from her. Indeed, if it were stolen, she would be entitled to have it back. Therefore, we must conclude that she sold/gave away/threw away the book without seeing any need to blot out or remove the inscription to her. Generally, privacy cases turn on whether the person had any expectation of privacy. If she turned her book out to the world, inscription intact, and with no limitations on how it could be used, how could she expect no one to see the inscription? That's like an author complaining that someone violated his/her privacy by reading the words in the book he wrote. It's absurd. If the issue is that Lopez mentioned her connection to the Kennedy campaign, that was published years ago in Time Magazine, that's already public knowledge. How could she expect privacy over something published in Time Magazine? She never, as best we can ascertain, sued Time, and probably more people read Time Magazine, or at least they did in 1960, than visit Mr. Lopez's website.

If the problem is that Ms. Abdouch thinks Mr. Lopez is unfairly profiting from the use of her name, that would mean that booksellers could never mention anything about a book's history. You better leave the “provenance” field blank on your listings. In this case, we suspect that Mr. Lopez profited more from the book's connection to John and Robert Kennedy, and author Richard Yates, than from its connection to Helen Abdouch. Do all of their estates have a right to sue Mr. Lopez for a violation of their privacy? If Ms. Abdouch is correct, could a dealer say anything about an inscription in any book, at least if the parties are still alive, without being subject to damages for violating that person's privacy? She does point out that she “has remained a private, non-commercial individual by choice,” and that entitles her to more consideration than a public figure, but she did choose to let the book go without removing her name, and she did participate in a public election in a sufficiently visible manner so as to get her name printed in Time Magazine.

I could feel more sympathy for Ms. Abdouch if this were a truly personal inscription, though I doubt it would make much difference legally. An inscription revealing a love affair, something really no one else's business, could elicit my sympathy, but “with admiration and best wishes” is hardly revealing of some private, personal matter. The only reason anyone, besides Ms. Abdouch and her friend, is even aware of this inscription is because she filed a lawsuit. Now, lots of people know about her. If anyone has violated Ms. Abdouch's privacy, it is she herself, not Mr. Lopez. If her real aim is to profit from the inscription, then she should have sold the book herself, not let it go however many years ago. All sales are final. Someone should realize there is no personal harm done, no unjust enrichment to a bookseller selling an ordinary inscribed book. If the 84-year-old Ms. Abdouch could not see this, then certainly her lawyer should have.