A California bookseller has gone to court to overturn a law detested by many sellers of autographed books in the state. On January 1, a new law went into effect that places what many consider onerous burdens on the sale of autographed books. While the assemblywoman who wrote the law later issued a statement claiming the law does not apply to booksellers, such statements are not a part of the actual law. There is still enough unclarity in the writing of the statute to leave many dealers fearful of the risks in selling anything with autographs. And so Book Passage, a San Francisco area chain of three stores, with the backing of the Pacific Legal Foundation, has gone to court to rid the state of the law.

First, here's a brief history of it. Section 1739.7 of the California Civil Code used to apply only to sports memorabilia. That is a field in which an enormous number of signed items are regularly sold, and it is rife with forgeries. Last fall, the legislature extended that to cover anyone "who is principally in the business of selling or offering for sale [autographed] collectibles in or from this state, exclusively or nonexclusively, or a person who by his or her occupation holds himself or herself out as having knowledge or skill peculiar to [autographed] collectibles..." The intent was reasonable, even if the legislature's response turned out not to be so. Anyone in the book trade will tell you if a signed book has not been professionally authenticated, or lacks a clear chain of possession, nothing can be assumed about that signature.

The problem with the law is that the requirements are, to say the least, burdensome. Sellers have to provide a Certificate of Authenticity for signed items, including a description of the item and the name of the signer, the purchase price and date of sale, an express warranty of authenticity, whether it is part of a limited edition and specifics about such an edition if so, whether the dealer is bonded or insured and proof thereof if so, the last four digits of the dealer's resale certificate, whether signed in the presence of the dealer, when, where, and the name of a witness to the signing, whether obtained from a third party and the name of that party if so, and the serial number of the item if it has one. There are also requirements of signage at the store or a show, and required messages in advertisements, describing this law. Dealers must retain copies of the certificates for seven years. Penalties for violations include not only actual damages, but a civil penalty of 10 times actual damages, court costs, attorney's fees, expert witness fees, and interest. Additional penalties may be added if the court finds the dealer's conduct "egregious."

While California sellers are naturally those most affected, the law does apply to out of state sellers selling signed material into the state (and to sales made by California dealers to out-of-state consumers).

It would be hard to overstate the uproar from the bookselling community. We have heard more from our members and readers on this story than just about anything else, and it applies mostly to just one state! The requirements are challenging, to say the least, both for the bookseller with a few autographed items in inventory and those who specialize in autographs. Who was it that witnessed Abraham Lincoln sign that book?

The response was so great that the assemblywoman who introduced this legislation wrote a letter stating, "Both the letter and the spirit of the law are clear that AB 1570 does not apply to booksellers. I refer specifically to how 'dealer' is defined in Section 1739.7 (a)(4)(A) which states that a dealer is defined as anyone who is 'principally in the business of selling signed collectibles' [emphasis added]. Bookstores, both as they are understood generally and many who communicated with my office, are not principally in the business of selling signed collectibles any more than a convenience store. It is true that some booksellers’ inventory include signed merchandise, including books signed by authors during special signing events. However, it is clear, even taking those items into consideration, a bookstore would not meet the bar of being ‘principally’ in the business of selling signed collectibles."

Assemblywoman Ling Ling Chang's letter is nice, but it isn't law. The law specifically says it applies to auctioneers and does not apply to pawnbrokers, but is silent on booksellers. Even if she is right that most booksellers aren't "principally" in the business of selling autographed items, they still could be considered "a person who by his or her occupation holds himself or herself out as having knowledge or skill peculiar to [autographed] collectibles." Her letter provided cold comfort to many concerned, even fearful booksellers.

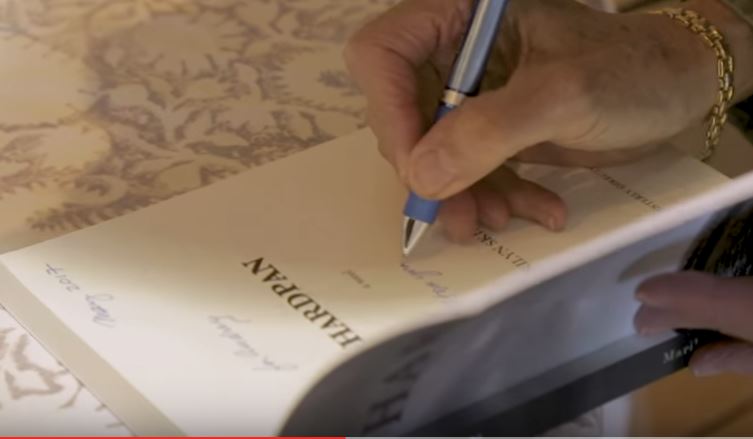

So into this fray stepped Book Passage and co-owner Bill Petrocelli, with legal assistance from the Pacific Legal Foundation. For Book Passage, there is no question that they are subject to the law and its voluminous requirements. They specialize in signed material, hosting 700 author book signings in their stores each year.

Book Passage calls for the overturning of the law on constitutional grounds, specifically, the First and Fourteenth Amendments. The first amendment claims pertain to free speech. The law makes it more difficult to sell autographed books, an infringement on communicating words within. It also infringes speech by making it practically impossible for them to host author talks/signings because of the burdens, thereby silencing the writers. The autographs themselves, they say, are a form of speech which is silenced by these demands. Furthermore, if some sort of regulation is needed, these are way too broad in that they interfere with free speech far more than necessary to achieve the law's aims.

The other claim pertains to the Fourteenth Amendment, adopted after the Civil War, guaranteeing equal protection under the law. Book Passage says that the exemption from the law for pawn shops and certain online retailers violates the equal protection rights of booksellers under the constitution.

We don't know where this all leads, but here are a few personal observations:

1. There is too much autograph fraud. It is way too easy. If something can reasonably be done, it should.

2. These rules are much too burdensome. They look like someone searched for remedies for every possible wrong and then wrote them up without considering the impact on honest business people. That letter by Assemblywoman Chang is essentially an admission of this.

3. This won't be an easy case. Constitutional claims against laws are really hard to win in court. Most court decisions involve disputes over facts, or interpretations of laws. Courts will willingly settle those, but are loath to overturn the "will of the people" as expressed by the laws of their elected representatives.

While the law makes it difficult for booksellers to sell autographed material, it does not prevent the sale of books as a whole, or even autographed ones if no claim or implied claim of authenticity is made. Nor does it prevent bookshops from holding author talks, although it may make such talks financially unprofitable. As for the equal protection claim, lots of laws affect people differently. There are probably laws in California that apply specifically to pawnshops but not booksellers. I, like many middle class people, have never understood why I am taxed at a higher rate than poor people, and at a higher rate than rich people. That doesn't sound very fair or equal to me, but welcome to the real world. I wouldn't get my hopes too high on this case, but I've been wrong before. This is in no way an endorsement of this flawed law, just an attempt to be realistic in expectations.

4. The legislature should scrap this law and get together with booksellers to see if something cannot be drawn up to reduce the problem without overburdening dealers. For example, the $5 minimum is ridiculous. A court case over $5? Someone who commits a $5 fraud should be reported to the authorities, but a civil suit to recover $5 is crazy. A $100 minimum would be more reasonable. Perhaps, instead of all the detailed requirements, a simple statement could be provided, one wherein the dealer can either state that the signature is authenticated and how, say there is no evidence to support authentication (and not advertise the book as autographed), or something in between, such as the provenance from the author's family may imply a connection but does not guarantee it. There must be a common sense answer.

![<b>Dominic Winter, Apr. 9:</b> Bible [English]. [<i>The Bible and Holy Scriptures conteyned in the Olde and Newe Testament,</i> 1562]. £3,000-5,000 Dominic Winter, Apr. 9: Bible [English]. [The Bible and Holy Scriptures conteyned in the Olde and Newe Testament, 1562]. £3,000-5,000](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/e47bb03e-3f3d-4f68-9e79-b0b2739ca87c.jpg)