A recent discussion with a few book lovers on social media ended up with the listing of the last known copy of an alleged extinct ‘edition’ on French soil: the rarest translation of Matthew G. Lewis’ The Monk—Le Moine. The only other known copy—with a prestigious provenance—lies on a shelf of the library of the University of Virginia. This is all about various editions and reversed engravings.

Matthew G. Lewis was only 20 when, in March 1796, he first published The Monk, a cornerstone of the Gothic Novel. As acknowledged, the dreadful plot of The Monk was inspired by various popular myths from Germany, Denmark or Spain. Yet, its modern style and narrative format make it unique. It contains the classical ingredients of a Gothic novel such as black masses, underground tunnels, blood, sex and supernatural manifestations. Of course, the critics were outraged by the so-called depraved content of the book. In the meantime, it became hugely popular with the public. It crossed the English Channel as soon as Year V (1797, revolutionary style), where it gave birth to a play in 5 acts (Barda, Year VI)— “inspired by the English novel,” reads the title page. The novel itself was picked up by Claude-François Maradan (1762-1823), whose bookshop was, interestingly, located “rue du cimetière / Street of the Cemetery.” Until the publication of the famous catalogue of Gérard Oberlé, in 1972 (De Horace Walpole à Jean Ray. Romans gothiques anglais, romans noirs), most bibliophilists considered that the 4 in-16°-volume set of 1797, with 4 engravings, was the first French edition. However, Oberlé reminded that Maradan was always following the same pattern when it came to publishing a book; first, he would put out an in-12° edition without illustration; then he would put out an in-16° edition with some engravings. Le Moine was no exception. So that the 3 in-12°-volume set of 1797 is now believed to be the very first edition.

According to the National Library of France (BNF), Maradan became an apprentice in 1787, and a bookseller a few months later. He went bankrupt in 1790—probably because of the Revolution of 1789—and a next time in 1803; but he was still publishing books by 1819, as testified by an edition of Le Moine in 3 volumes that came out that very year. “He was probably related to the Parisian engraver François Maradan (1766-circa 1816),” reads the website of the BNF. Le Moine apparently sold quite well, since it was reprinted the same year; but this time with 4 engravings. The identity of the engraver is unknown. Did Maradan call upon his alleged relative from Paris, François? One thing is for sure, the engraver did a very good job. Gorgeous and attractive, the plates represent the most dramatic scenes from the book: Ambrosio trying to resist a half-naked nun, a bloody black mass held in an underground passage, a mysterious masked woman stepping out of a creepy castle, or the devil grabbing Ambrosio by the hair under a stormy sky.

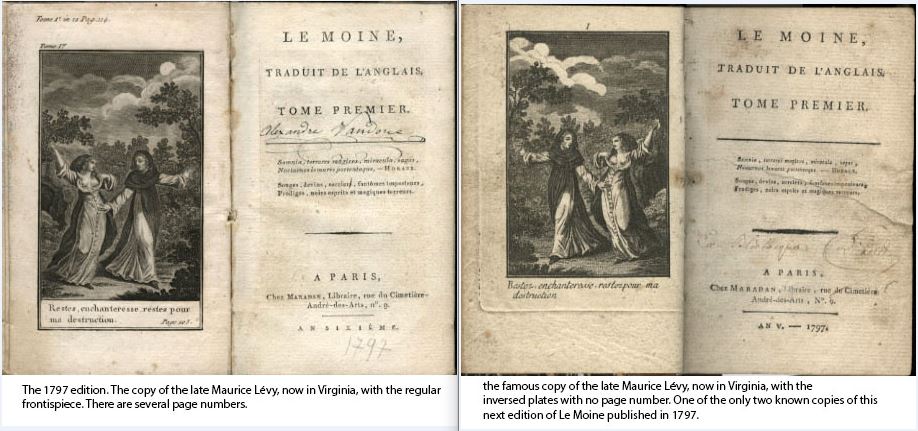

The bookseller made sure the clients who had bought the first edition could upgrade their copy by buying the engravings separately; consequently, he featured the page numbers of both editions on them. In the top right-hand corner of the digitalized copy available at googlebooks, (AN V, 1797) the plate reads: “Tome 3e. in 12 Page...” And in the top left-hand corner: “Tome 4e”. The page number is also to be found in the bottom right-hand corner: “Page 186.” As a matter of fact, it is quite common to find the first edition bound with the engravings of the second one.

The ‘Inversed set’

Florian Balduc is a French bookseller and the head publisher of Otrante editions, who recently listed the various sets of engravings of Le Moine on his website. Indeed, when he compared the engravings, he realized that they vary from one edition to the other. Here are the ascertained sets:

1) The original one, featuring the page number of the second edition. “The most common,” says Florian Balduc.

2) The same set as above, featuring the page numbers of both the first and the second editions—so the buyers of the first edition could upgrade their copies.

3) The same set, with no page number at all, as reported by another bookseller.

4) The engravings of the edition of Year VI (1798), which are slightly different. “They are more ‘raw’ and certain parts have been drawn with less details.”

5) What we will call ‘the inversed set’, since the four plates are printed in reversed orientation. “I only know one copy in the world to feature these plates,” said Florian Balduc. “And it is the copy of the late Maurice Lévy.” In the early 1960s, Lévy, who was studying at La Sorbonne, went for three months to Virginia, USA. There, he read the entire Sadleir-Black Collection of Gothic Fiction in order to complete his memoir entitled The English ‘Gothic’ Novel, 1764-1824. It “became a standard source and helped to revive scholarly interest in the field,” writes Nicole Bouché, Director of Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library. “And Lévy became a recognized authority on the gothic genre. Maurice’s final work, a scholarly edition of Matthew Gregory Lewis’ classic gothic tale, The Monk, was published posthumously in 2012.”

Before he passed away in 2012, he bequeathed his collection—“which, although relatively modest in size when compared to others,” as he once described it, “has the advantage of illustrating the extraordinary vogue of the 'roman noir' during the French Revolutionary period”—to the Library of Virginia where he had enjoyed such a good time. Among these treasures are several French editions of Le Moine, including one with the reversed engravings. Of course, this detail didn’t escape Lévy’s scrutiny. “He was fascinated by the illustrations found in French Gothic novels,” writes David Whitesell on the website of the Library of Virginia, “and in 1973 he published a book on the subject, Images du roman noir.” According to Whitesell—who seems to still consider the 4 in-16° volume set as the first edition—, the success of the book took Maradan by surprise: “It is likely that the publisher, not anticipating the need for a second edition, neglected to save the copperplate and therefore had to commission a new plate of the same image. In copying the original frontispiece (which printed in reverse orientation from the design as etched on the copperplate), the etcher necessarily reversed the image!” It makes sense, except that Maradan was used to put out a second in-16° edition of his publications; unless he had not anticipated the need for a second second edition.

Anyway, the plates are reversed so that the characters of the first one are walking in the opposite direction, the masked woman of the second one is right-handed, the nun is bleeding from the left arm on the third one, and on the last one, the devil is holding the parchment of Ambrosio’s damnation in his left hand, not in the right one. But there are other differences as well: the engravings have no frame and no page number, for instance. A simple number, from 1 to 4, indicates the volume they relate to, as they were the frontispieces of each volume. The captions, for their part, have remained the same.

![<b>Koller, Mar. 26:</b> Wit, Frederick de. Atlas. Amsterdam, de Wit, [1680]. CHF 20,000 to 30,000 Koller, Mar. 26: Wit, Frederick de. Atlas. Amsterdam, de Wit, [1680]. CHF 20,000 to 30,000](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/2214ca86-0dc9-47be-8bc5-99d9f1c2aa1f.jpg)

![<b>Koller, Mar. 26:</b> Hieronymus. [Das hochwirdig leben der außerwoelten freünde gotes der heiligen altuaeter]. Augsburg, Johann Schönsperger d. Ä., 9. Juni 1497. CHF 40,000 to 60,000. Koller, Mar. 26: Hieronymus. [Das hochwirdig leben der außerwoelten freünde gotes der heiligen altuaeter]. Augsburg, Johann Schönsperger d. Ä., 9. Juni 1497. CHF 40,000 to 60,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/b8b6a630-a01a-4220-ae77-38540d6c898d.jpg)

![<b>Forum, Mar. 27:</b> Book of Hours, Use of Rome, illuminated manuscript in Latin, on vellum, 26 fine hand-painted miniatures, 17th century dark brown morocco, [Lyon], [c. 1475 and later c. 1490-1500]. £25,000 to £35,000. Forum, Mar. 27: Book of Hours, Use of Rome, illuminated manuscript in Latin, on vellum, 26 fine hand-painted miniatures, 17th century dark brown morocco, [Lyon], [c. 1475 and later c. 1490-1500]. £25,000 to £35,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/1d4e3614-8c6e-4405-9784-fccc9af6f069.png)

![<b>Forum, Mar. 27:</b> Brontë (Emily) <i>The North Wind,</i> watercolour, [1842]. £15,000 to £20,000. Forum, Mar. 27: Brontë (Emily) The North Wind, watercolour, [1842]. £15,000 to £20,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/cdae56c0-f6c2-49f9-aa96-cb45addacd4e.png)

![<b>Forum, Mar. 27:</b> [Austen (Jane)] <i>Emma: A Novel,</i> 3 vol., first edition, for John Murray, 1816. £10,000 to £15,000. Forum, Mar. 27: [Austen (Jane)] Emma: A Novel, 3 vol., first edition, for John Murray, 1816. £10,000 to £15,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/ba9a41af-fc2f-4232-b3ab-c2df1eee9335.png)

![<b>Forum, Mar. 27:</b> Iceland.- Geological exploration.- Bright (Dr. Richard )and Edward Bird. Collection of twenty original drawings from travels in Iceland with Henry Holland and George Mackenzie, watercolours, [1810]. £20,000 to £30,000. Forum, Mar. 27: Iceland.- Geological exploration.- Bright (Dr. Richard )and Edward Bird. Collection of twenty original drawings from travels in Iceland with Henry Holland and George Mackenzie, watercolours, [1810]. £20,000 to £30,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/2a143987-f930-4a0f-a2e9-c1d7c73846c3.png)

![<b>Forum, Mar. 26:</b> Beckford (William) [Vathek] <i>An Arabian Tale,</i> first (but unauthorised) edition, Lady Caroline Lamb's copy with her signature and notes, 1786. £2,000 to £3,000. Forum, Mar. 26: Beckford (William) [Vathek] An Arabian Tale, first (but unauthorised) edition, Lady Caroline Lamb's copy with her signature and notes, 1786. £2,000 to £3,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/3b9e9f17-a38a-48d3-8002-704791674917.png)

![<b>Forum, Mar. 26:</b> Pellar (Hans) Eight original book illustrations for 'Der verliebte Flamingo' [together with] a published copy of the first edition of the book, 1923. £6,000 to £8,000. Forum, Mar. 26: Pellar (Hans) Eight original book illustrations for 'Der verliebte Flamingo' [together with] a published copy of the first edition of the book, 1923. £6,000 to £8,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/2e38d43d-301f-4367-aa55-51fffc7fe85b.png)